Despite tremendous efforts to prevent type 2 diabetes (T2DM), the incidence of obesity continues to increase all over the world [1,2]. A recent large cohort study has shown that obesity is associated with cardiometabolic disorders in most individuals [3], although an index of obesity, the body mass index (BMI), is not the sole marker of obesity, and abdominal fat may be more closely associated with morbidity [4]. This suggests that obesity, including “metabolically healthy” obesity, is rarely healthy in the long term, emphasizing the importance of prevention or treatment of obesity, irrespective of the current metabolic status.

Weight loss by caloric restriction substantially improves glucose metabolism in patients with recent-onset T2DM [5], suggesting the importance of an early intervention. On the other hand, in the same series of studies, the improvement of glucose tolerance by caloric restriction was shown to be dependent on the improvement of beta cell function, irrespective of reduction of either liver or pancreatic fat [6]. Recent advances in in vivo beta cell imaging techniques have revealed that beta cell function and mass are related to each other and both progressively decline with the disease course in subjects with glucose intolerance [7]. Thus, it can be assumed that the improvement of beta cell function is dependent on the residual amount of beta cell mass.

Prevention of obesity is also important for preventing the onset of T2DM in adolescents. Recent studies have shown that the adolescents with impaired glucose tolerance or recent-onset T2DM show greater insulin secretion, compensating greater insulin resistance, compared with the adults with glucose intolerance [8,9]. I have recently proposed that excess beta cell workload is the cause of beta cell loss, i.e., the beta cell workload hypothesis [10]. Dysfunction and/or death of beta cells due to overwork may be analogous to “karoshi” in our society, which may be more readily understandable by the general public. Greater workload of beta cells in adolescents with glucose intolerance will accelerate the progression of beta cell loss, consistent with recent observations [11-13]. Thus, there should be further focus on the prevention of obesity in the next generation.

A healthy lifestyle is critical to prevent obesity and T2DM. A healthy lifestyle includes appropriate caloric intake, reduced intake of saturated fat and sugar-containing snacks and beverages, increased intake of vegetables and unsaturated fat, an increase in physical activity [14-17], and possibly avoiding even a small amount of alcohol intake [18].

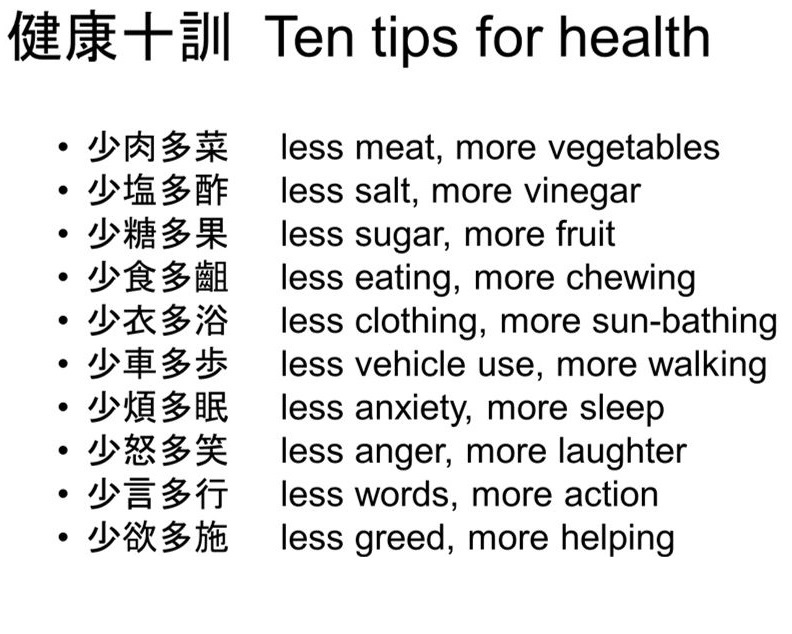

However, it is not very recently that the importance of a healthy lifestyle for longevity has been proposed. In the 18th century, during the Edo era in Japan, there were ten tips for health (Figure 1) [19]: (1) less meat, more vegetables; (2) less salt, more vinegar; (3) less sugar, more fruit; (4) less eating, more chewing; (5) less clothing, more sun-bathing; (6) less vehicle use, more walking; (7) less anxiety, more sleep; (8) less anger, more laughter; (9) less words, more action; and (10) less greed, more helping. This precious knowledge and experience of our ancestors are likely to be applicable to our current society to reduce the incidence of diabetes and extend healthy aging.

Figure 1. Ten tips for health proposed in the 18th century in Japan [19].

Received date: September 26, 2018

Accepted date: October 03, 2018

Published date: October 10, 2018

None

None

© 2018 The Author. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (CC-BY).

Diabetes control in the studied population could be too strict, and consequently, hypoglycemia in these patients could play a role in the major decline of cognitive function. Therefore, avoiding treatments that could lead to hypoglycemia in these patients could be very important. The aim of the treatment of diabetes in elderly patients is focused on stabilization, prevention of acute complications, and improving the quality of life.

A paradigm shift in type 2 diabetes may contribute to the reinforcement of new research questions and further improvement of diabetes care in clinical practice.

Authors report a young girl with an HNF1β mutation, who had a history of neonatal cholestasis, persistent liver dysfunction, and developed insulin-dependent diabetes without renal involvement. Further, authors review the literature related to the hepatic involvement associated with HNF1β mutations.

The authors examined the appropriateness of an IIP, which was modified to fit the Japanese population, who were usually less obese and less insulin-resistant. This IIP maintained blood glucose levels within the target range in patients who underwent open-heart surgery as equally well as the previous empirical therapy. These findings confirm the efficiency and safety of our IIP with less burden in blood glucose management of Japanese patients.

A higher titer of IA-2Ab reflects a reduced pancreatic size in the patients with Type 1 diabetes (T1D), especially in those with the acute-onset form of the disease. The potential mechanisms underlying the reduced pancreatic size might differ between acute-onset T1D and slowly progressive insulin-dependent diabetes mellitus. The authors investigated the relationship between islet autoimmunity and pancreatic size in the Japanese patients with T1D.

Saisho Y. Ten tips for healthy longevity. Diabetes Endocrinol 2018;1(1):5. https://doi.org/10.24983/scitemed.de.2018.00084