Background: Supraclavicular flap is an excellent fasciocutaneous flap for head and neck reconstruction due to its close color and texture match. In general, long flaps are required, but with the risk of distal necrosis. The aim of this study is to assess the relationship between the length and distal end necrosis of the supraclavicular flap.

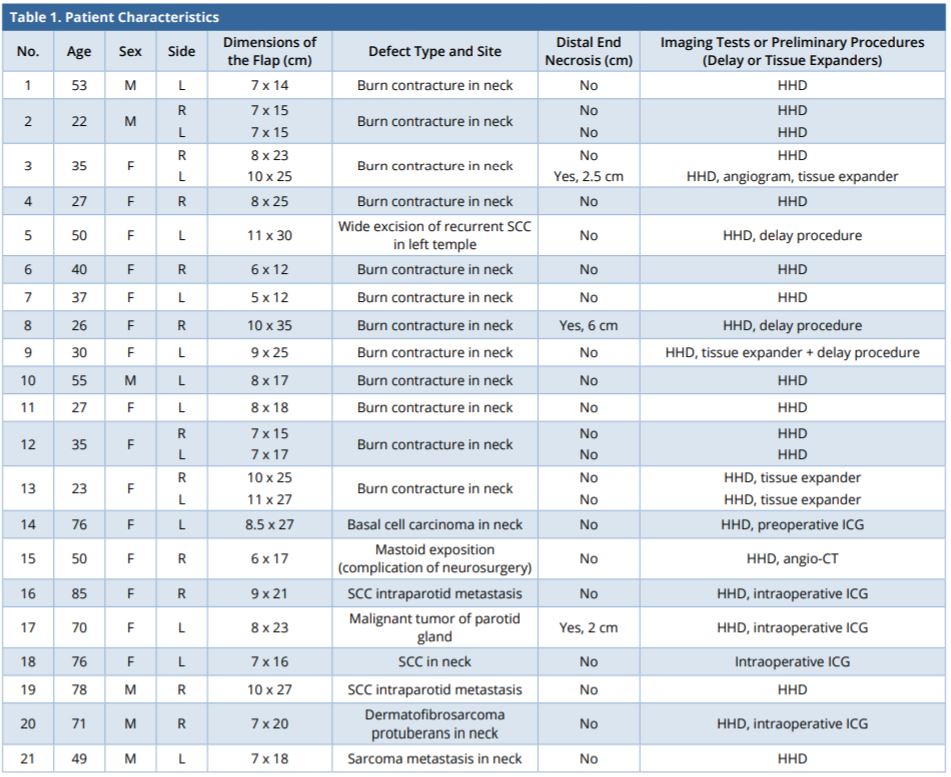

Methods: Between 2013 and 2017, 21 patients underwent head and neck reconstruction surgery, in which 25 supraclavicular flaps were used. In 12 cases, the flaps were used for reconstruction following release and excision of burn contractures, whereas the remaining 9 patients had flaps following wide excision of tumors. Different imaging techniques were used to facilitate the design and guide the dissection of the flap, and modification procedures were performed to prolong the survival length of the flaps.

Results: The length of the 25 flaps used varied according to the patient’s needs. In average, the length ranged from 12-35 cm with a mean length of 20.76 cm. There was no total flap loss; however, 3 of the flaps (12%) resulted in distal end necrosis. All the flaps with distal necrosis had a length of 23 cm or more regardless of whether the modification procedures were performed or not, while the flaps with length below 23 cm had no necrosis (14 flaps).

Conclusion: The distal survival of the supraclavicular artery island flap is reliable up to 22 cm, but the flaps above that size will increase the risk of distal necrosis with or without modification procedures.

The supraclavicular flap has gained popularity in recent years as a reliable and easily harvested flap, which is ideal for head and neck reconstruction. The flap is based off an axial vessel branching from the thyrocervical trunk or transverse cervical artery. The color match, thinness, pliability, and the hair-free skin of supraclavicular artery flap parallel that of the head and neck region and provide a superior cosmetic outcome when compared to free tissue transfer flaps from the other regions such as the forearm, abdomen, or thigh [1-3].

In the year 1842, Thomas Mutter in Philadelphia described a random flap in the shoulder region [3-5]. In 1903, Toldt, an anatomist, first illustrated and named the vessel as arteria cervicalis superficialis. It originates from the thyrocervical trunk exiting between the trapezius and sternocleidomastoid muscles [2].

Kazanjian and Converse performed the first clinical application of a flap from the shoulder area in 1949 and they named it as “in charretera flap” or acromial flap [3,6,7]. The supraclavicular flap was first described by Lamberty in 1979 as an axial pattern fasciocutaneous flap [8].

In 1983, Lamberty and Cormack, in an anatomical study on cadavers, found a vessel cephalad to the clavicular insertion of the trapezius muscle and they named it as the supraclavicular artery [9]. At the beginning of beginning in the 1990s, Pallua et al. “rediscovered” this flap and popularized its use by performing detailed anatomical studies examining the vascularity of what is known today as the supraclavicular island flap [10,11]. They published several clinical series of supraclavicular flaps for reconstruction of post-burn neck contracture, and also in oncologic head and neck reconstruction. They found the flap safe and reliable for immediate resurfacing of cervical defects [5,11-13].

Di Benedetto et al. in 2005 reported this flap as reliable for covering intraoral defects after oncologic resection [14]. Epps et al. and Emerick et al. described the use of supraclavicular flap for the restoration of the parotidectomy defects [15,16]. Chiu et al. described the use of the supraclavicular flap for functional pharyngeal reconstruction [17].

In the past decade, this flap has been widely used and discussed [18- 20]. Anatomical studies supporting its use have been performed [21-23]. The sensate [24], the pre-expanded [13,25,26], the delayed [8,27], the prefabricated [27], the superthin [13,28], the folded [29,30], and the bilobed versions [30-32] of supraclavicular flap have also been developed.

The use of supraclavicular flap for head and neck reconstruction was well described in many articles [1,2,4,11-17,19,20,23-26,28,29,31,33-40] with a special focus on the length of flaps and their rate of necrosis. The aim of this study is to check the relation between the length and distal end necrosis of supraclavicular flap.

In the time frame between July 2013 and February 2017, 21 patients underwent reconstruction with supraclavicular island flap for head and neck defects following the release and excision of burn contractures and wide excision of tumors.

This study was conducted in the Burns and Plastic Surgery Department in Sulaimaniah Teaching Hospitals in Sulaimani, Iraq, and the Plastic Surgery Departments of Hospital de la Santa Creu i Sant Pau and Hospital del Mar in Barcelona, Spain. The patients who required reconstruction with pedicled supraclavicular island flaps for head and neck defects in both centers were included in this study. None of the supraclavicular island flaps were used for aerodigestive tract reconstruction.

Twenty-five supraclavicular artery island flaps were used for 21 patients. From the 21 patients that underwent reconstruction, 12 cases had post-burn neck contractures and scarring, which were excised and the defects were then reconstructed using the supraclavicular flap, whereas, the other 9 patients underwent supraclavicular flap reconstruction for the defects following wide excision of head tumors.

Smoking could be a factor that might affect the vascularity of the flaps. In this study, it was noted that all the male patients were ex-smokers or they had quit smoking prior to the operations, whereas, all the female patients were non-smokers.

All the surgical procedures, including the flap harvest and the reconstruction, were performed under general anesthesia. Different imaging techniques such as Hand-held Doppler, computerized tomography angiogram, fluoroscopy angiogram, and Indocyanine green angiogram were used in the preoperative or intraoperative stage for some patients in order to localize or map the pedicle (Table 1). In addition, modification techniques such as delay procedures and tissue expansion were also performed as a separate procedure in 6 flaps when more length was required, aiming to improve distal vascularity and facilitate donor site closure.

Supraclavicular artery island flap dissection started from distal to proximal edge, incising the inferior border of the flap as an exploratory incision. The dissection followed in a subfascial plane until the supraclavicular pedicle was identified. Then, the superior incision was completed in order to raise the skin paddle. Supraclavicular pedicle isolation, usually, was not necessary to transpose the flap to the defect. Clavicle periosteum elevation or clavicle bone division was unnecessary.

Depending on the skin laxity or the reconstructive demands, tunnelization or depithelization of the neck skin was chosen. Depithelization of a part of the skin paddle is necessary when the tunnelization is performed to transpose the flap to the defect. It may be necessary to do a book incision in the neck skin if the tunnelization puts too much tension on the flap.

CT, computed tomography; CTA, computed tomography angiography; F, female; HHD, handheld doppler; ICG, indocyanine green; ICGA, indocyanine green fluorescent angiograms; L, left; M, male; R, right; SCC, squamous cell carcinoma.

A total of 25 supraclavicular artery island flaps were used for 21 patients with head and neck defects. Results of the study are shown in Table 1.

The procedure was performed in 15 female and 6 male patients, the mean age of the patients was 48.3 years. Four patients had bilateral flap reconstruction. Eleven flaps were harvested from the right side of the neck, whereas the remaining 14 flaps were taken from the left side.

The size of the supraclavicular flaps varied in length and width according to the patient’s needs. On average, the length ranged from 12 to 35 cm, with a mean length of 20.76 cm (standard deviation 6.01), whereas the width of the flaps ranged from 5 to 11 cm resulting in a mean width of 8.06 cm (standard deviation 1.59). Donor sites were directly closed in 20 flaps, but five cases (No. 1, 5, 9, 14, and 19) required split-thickness skin grafting in the area that was not possible to be closed directly.

All the flaps had distal viability after inset. There was no flap loss, but 3 flaps resulted in distal end necrosis (12%). Four cases (No. 3, 5, 8, and 17 in Table 1) had distal flap congestion during the early preoperative stage. Salvage measures were quickly established. Dressings or distal stitches were removed in order to avoid any tension (cases 5 and 8). Local warm measurements plus application of local heparin gel every 8 hours were performed to increase the distal perfusion of the flap in the 4 cases.

Consequently, the vascularity of case No. 5 improved and distal closure was performed in 3 days. The other 3 flaps resulted in distal necrosis and they were managed according to their magnitude of necrosis. Two flaps with a small necrosis (2 and 2.5 cm) were managed with dressings and secondary healing without sequelae, while the flap with bigger necrosis (6 cm) required debridement and approximations for closure.

Case 1 (No. 15 in Table 1)

50-year-old-female, required debridement of osteomyelitic mastoid bone as a complication of pontocerebellar angle meningioma approach (Figure 1A). Supraclavicular flap with 17 x 6 cm skin paddle was used for bone coverage (Figure 1B and 1C).

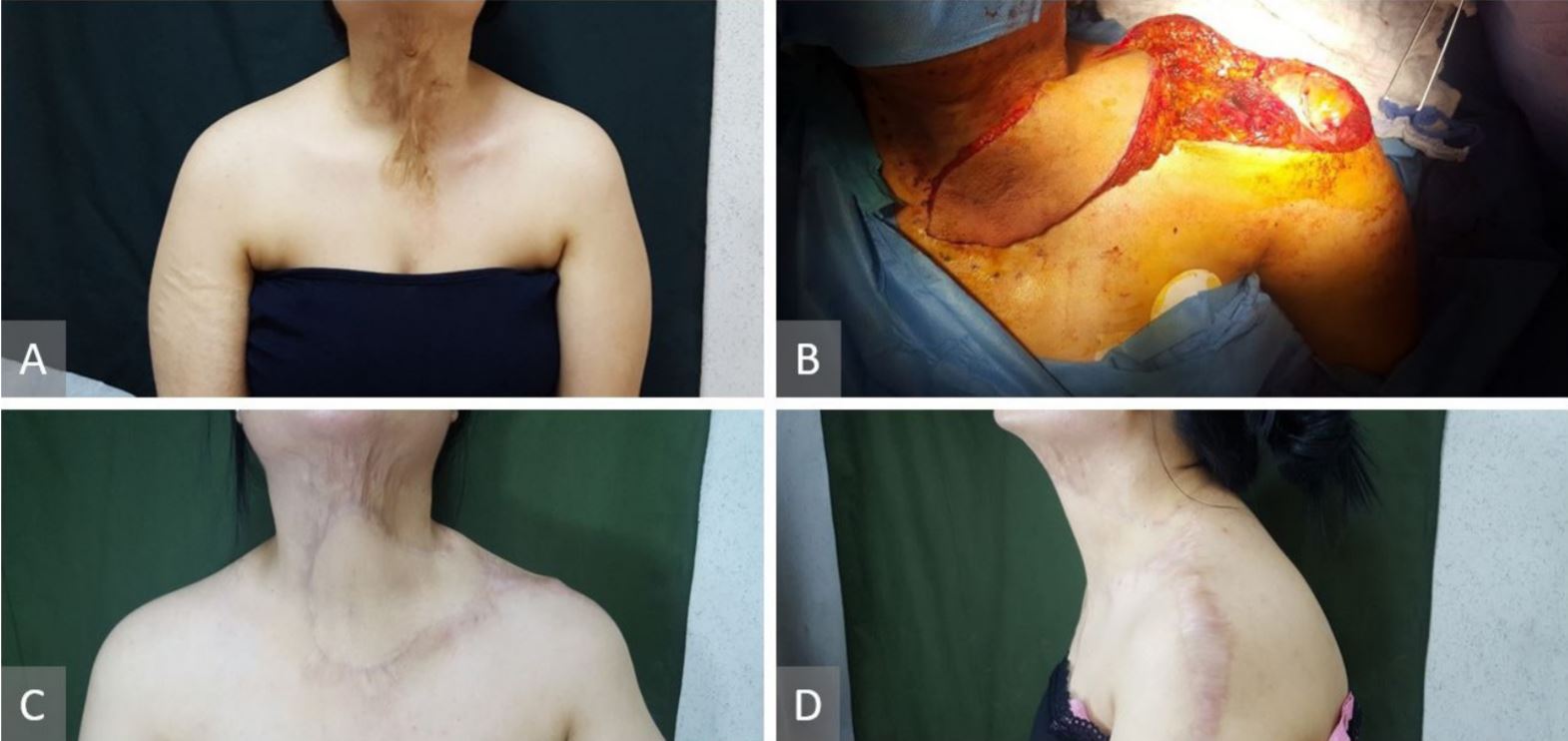

Case 2 (No. 3 in Table 1)

35-year-old-female, post-burn hypertrophic scar and contracture on the neck and chest (Figure 2A). Three surgical procedures at different time were performed. The first surgical procedure was a partial excision of the neck scar and an 8 x 23 cm right supraclavicular flap was used to fill the defect. The second procedure included a left pre-expanded supraclavicular flap and also tissue expander colocation under the right supraclavicular flap in the neck (Figure 2B). The third procedure included the excision of the remaining scar, expanders removed, 10 x 25 cm left supraclavicular flap raised, both flap inset done, and donor sites were closed directly (Figure 2C and 2D). Further scar revision and Z plasty in the neck were performed as a separate minor procedure.

Case 3 (No. 5 in Table 1)

50-year-old-female with a fourth recurrence of squamous cell carcinoma (SCC) of the scalp and temple, involved left temporo parietal area and left auricle (Figure 3A). The CT scan showed infiltration of the outer table of the skull. A two-stage surgical procedure was planned. In the first surgical session, a flap of 11 cm x 30 cm was delayed to increase the survival length of the flap through the delay phenomena. In the second stage (3 weeks later), a multidisciplinary team of neurosurgeons, otolaryngologists, and plastic surgeons performed wide tumor excision including the auricle and part of the skull bone, and the defect was reconstructed with a supraclavicular flap of 11 cm x 30 cm, and the donor site was covered with a split-thickness skin graft (Figure 3B, 3C, and 3D).

Case 4 (No. 9 in Table 1)

30-year-old-female with post burn neck contracture (Figure 4A). A pre-expanded and delayed left supraclavicular flap of 9 x 25 cm was used for reconstruction after the neck scar excision (Figure 4B, 4C, and 4D).

Case 5 (No. 14 in Table 1)

6-year-old-female with Cluster A disease and local advanced basal cell carcinoma in the left cheek (Figure 5A). The tumor was widely excised and the defect reconstructed with 27 x 8.5 cm supraclavicular flap. Intraoperative ICG evaluation was performed to mark the pedicle and design the flap. The donor site was closed with a split-thickness skin graft and the flap completely survived (Figure 5B, 5C, and 5D).

Figure 1. (A) Intraoperative view of the defect and the right supraclavicular flap designed. (B) Flap raised and the supraclavicular vessel isolated on the green background. (C) The flap inset done and the donor site closed directly. (D) Six-month postoperative result.

Figure 2. (A) Post-burn hypertrophic scar and contracture on the neck and chest. (B) Left pre-expanded supraclavicular flap and also tissue expander colocation under the right supraclavicular flap in the neck. (C) Post-operative view of the neck reconstruction with right and left supraclavicular flaps and the donor site closed primarily. (D) Post-operative view of the neck reconstruction with right and left supraclavicular flaps and the donor site closed primarily.

Figure 3. (A) Squamous cell carcinoma of the scalp and temple, involved left temporoparietal area and left auricle. (B) The supraclavicular flap of 30 X 11 cm marked to be delayed. (C) The flap inset. (D) Three-month postoperative view.

Figure 4. (A) Post burn neck contracture. (B) Pre-expanded and delayed left supraclavicular flap of 9 x 25 cm has been raised for neck defect reconstruction after the neck scar excision. (C) Six-month postoperative view. (D) Six-month postoperative view.

Figure 5. (A) Basal cell carcinoma in the left cheek. (B) Vascular pedicle marked and flap raised. (C) Flap inset and donor site closed with a split-thickness skin graft. (D) Six-month postoperative result.

The results of this study have been analyzed to see the relationship between the flap length and distal end necrosis. According to the data obtained in the results section of this report, the distal end vascularity of the supraclavicular artery island flap was reliable up to 22 cm, but the flaps with the size of 23 cm and above increased the risk of distal necrosis, regardless of whether the modification procedures were performed or not. Due to the presence of modification procedures in 6 flaps above 23 cm length, the statistical analysis couldn’t be reported without bias as the group of the flaps above 23 cm was nonhomogeneous.

From the literature review of supraclavicular flaps for head and neck reconstruction in PubMed search engine, 26 articles [1,2,4,11- 17,19,20,23-26,28,29,31,33-40] were found that had used supraclavicular flaps for head and neck reconstruction and had clearly stated the length of flaps and their rate of necrosis (Table 2). The rate of necrosis varied according to the size of the flaps, and only a few of the published articles clearly associated the rate of necrosis with the definite length of the flaps.

The following articles have discussed the relationship between the length of the supraclavicular flap and distal necrosis. Ismail et al., in a study that involved 20 supraclavicular flaps ranged from 16 cm to 25 cm in length (mean 21.7 cm), reported that 7 flaps (35%) showed partial distal necrosis, either in the form of superficial epidermolysis in 5 cases or full thickness necrosis of the distal two centimeters in 2 cases. They also reported that in all their cases with distal necrosis, the flaps were 23 cm or more in length [31]. Ismail et al. recommended that supraclavicular flaps longer than 22 cm were not harvested immediately, and they recommended modification procedures such as flap expansion before harvesting [31]. Similarly, Kokot et al., in a study that involved 45 flaps with a mean length of 21.4 cm, reported that the flap length greater than 22 cm significantly correlated with flap necrosis [19]. In a different article, Vinh et al. reported that a unilateral supraclavicular flap with an average size of 22 x 10 cm can be elevated safely [23]. Loghmani et al. in a study with 41 flaps, where the range of flap size was 18 ± 6 cm in length with 3 cases of distal necrosis, had also found that the supraclavicular flap could be safely elevated, provided it was within 20 x 10 cm [36]. On the other hand, Telang et al.’s study found that the supraclavicular flap could be safely elevated within the dimensions of 20 × 10 cm, and the use of tissue expansion greatly amplified the total area available [37]. The results in the above discussed 5 articles strongly support our results that the flaps of 23 cm and above correlate with distal necrosis.

Nevertheless, the results of a published article by Kokot et al. contradict with the findings of the above-mentioned papers. They had used 22 supraclavicular artery flaps ranging 16-28 cm in length (mean length of 21.8 cm) with partial skin flap necrosis occurred in 2 patients. In this article, it was reported that no statistical correlation was found between flap necrosis and flap length [35].

In our study, the effect of the modification procedures (the delay and the tissue expansion) clinically was not clear on the survival of the distal end of the flaps, but apparently, the expansion procedures helped in closing the flap donor sites directly up to 11 cm width.

The limitation of this study was about the number of flaps and, in particular, the number of modification procedures performed for the flaps. Therefore, in the future, a study with a larger sample size is recommended to achieve more reliable clinical and unbiased statistical results for modification procedures in terms of their effect on the survival length of the supraclavicular flap.

Correct knowledge of the relation between the length of the flap and the magnitude of the distal necrosis is essential in reconstructive surgery to avoid necrosis of the distal margin of the flap. The distal survival of the supraclavicular artery island flap is reliable up to 22 cm, but the flaps above that size will increase the risk of distal necrosis with or without modification procedures.

Received date: December 30, 2017

Accepted date: June 28, 2018

Published date: November 12, 2018

None

None

Informed consents were obtained from the patients.

© 2018 The Author (s). This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (CC-BY).

Authors proposed a simple innovative technique that helps in achieving a clear surgical field at the time of venous repair by diverting the venous bleeding through a glove finger and at the same time preventing venous congestion of the flap.

The supraclavicular flap has gained popularity in recent years as a reliable and easily harvested flap with occasional anatomical variations in the course of the pedicle. The study shows how the determination of the dominant pedicle may be aided with indocyanine green angiography. Additionally, the authors demonstrate how they convert a supraclavicular flap to a free flap if the dominant pedicle is unfavorable to a pedicled flap design.

The main problem with the paper is that it is focused on the relationship between flap length and development of flap necrosis, but the data provided are not properly analyzed (non-homogeneous sample of patients). I suggest the following modifications to strengthen this article.

Title: Please use the correct name: Supraclavicular artery island flap, not perforator flap. Abstract section: “Also, the supraclavicular flaps that are greater than 23 cm in length results in an increased risk of distal necrosis, with statistically significant relation, (P = 0.039)”. This sentence should be moved to results. Table 2 should be properly cited in the results, not in the introduction. Methods section suffer from absence of surgical technique described, information about pedicle dissection (is there constant need to see and dissect the vascular pedicle?), elevation of clavicular periosteal layer, proximal bridge management (book incision, decortication), tunnellization, should be provided. “Supraclavicular flaps that were used for reconstruction of the aerodigestive tract were excluded from this study”. Why? Please explain. “In addition, modification techniques such as delay procedures and tissue expansion were also performed as a separate procedure in some of the flaps”, this is the weak aspect of the paper (non-homogeneous sample of patients). In the Results section: supraclavicular island flaps are usually low-flow grafts which show a weak vascularization in the first 48-72 hours, both in their arterial and venous networks, during this time choke vessels start to open, and revascularization also starts from wound margins, allowing to obtain successful results in the long-term follow-up. Please provide information on immediate and long term flap course and on strategies to salvage critical flaps. In Case Reports section: Cases 1 and 5 should show long-term follow-up, not intraoperative view at the end of the surgery. In Discussion section: “According to the data obtained in the results section of this report, as the length of flap increases, the rate of distal end necrosis also increases”, this concept is well known from the previous papers on this topic. “27.27% of the flaps with a length of 23 cm and above presented distal end necrosis (11 flaps of the series)”, as the authors themselves admit (“The limitation in this study was about the number of the flaps and in particular the number of modification procedures performed for the flaps”), these data are influenced by the fact that 6/11 flaps were delayed or expanded, preliminary procedures which aim at reducing the risk of partial necrosis; the real rate of partial necrosis cannot be calculated on the provided group of patients and the sentence “The statistical analysis shows that the relation between flap length and distal necrosis has a significant P value of 0.039, which means that the length of the flap affects the distal vascularity” is not supported by a correct evaluation of the patients included. Finally, the Conclusions are not new and not supported by correct statistical analysis.

ResponseThank you very much for revising our article and giving us valuable comments to improve the quality of the article. We have changed, removed and added parts and corrected the article according to your comments. Please review the revised article. Itemized corrections are shown in each section of the article according to your comments. Strike through parts indicate removed texts and red font parts indicate paragraphs/sentences added in the revised manuscript.

The authors have addressed my concerns. However, this article should be published as an original article instead of review article. It can be published after minor revision.

This is a well-written article after the revision. I suggest the title to be changed to "Supraclavicular Artery Island Flap: Relation between Length and Distal End Necrosis".

Sheriff H, Garcia CV, Jaber S, Ojea DB, Kareem SS, Garrido MF, Masia J. Supraclavicular artery island flap: Relation between length and distal end necrosis. Int Microsurg J 2018;2(1):5. https://doi.org/10.24983/scitemed.imj.2018.00089