Initial presentation with cervical lymphadenopathy poses a wide array of differential diagnoses and prognoses. We report four non-tuberculous granulomatous lymphadenitis cases with temporal and geographic clustering, unresponsive to medical management that warranted modified neck dissection to facilitate cure. To help recognize these atypical cases, we describe clinical and radiological features of this condition. We also present our experience with the management and the outcomes of this uncommon disease. In the span of one year (2016-2017), four patients aged 2 to 14 years with massively enlarged neck masses were referred for surgical evaluation. All patients warranted neck dissection and removal of pathological cervical lymph nodes (LN). Patient presentation, testing, treatments, and follow-up were reviewed. The neck masses ranged from 3 x 3 cm to 7 x 7 cm on physical exam with no accompanying infectious symptoms. Extensive testing did not reveal a diagnosis. Interestingly, all the four pathological analyses revealed granulomatosis with variable degrees of necrosis (focal to extensive). The follow-up revealed no evidence of recurrence in any of the patients. The patients with isolated massive granulomatous cervical lymphadenopathy not related to any known disease, infectious or malignant etiology, could be categorized under “Granulomatous Lymphadenopathy of Unknown Cause”. After exclusion of common causes of lymphadenitis in children, early consideration should be given for radical LN excision as is done in cases of atypical mycobacteria to ensure cure.

Cervical lymph node (LN) enlargement in the pediatric population is most common due to a benign inflammatory process [1]. The rates of malignant causes range from 13 to 33% in patients presenting with suspicious neck adenopathy that requires excision biopsy [2]. Surgical intervention in most instances involves obtaining tissue by means of an excision biopsy to diagnose or exclude a malignancy such as lymphoma. LNs having features such as size greater than 1.5 cm, hard and fixed to palpation, possible atypical mycobacterial infection, having a discharging sinus, refractory to antibiotics, or persistent (longer than 6 weeks) mandate biopsy to exclude malignancy or for curative purposes [3]. Thorough history taking and complete physical examination are central to the workup of lymphadenopathy. Accompanying signs and symptoms narrow down the diagnosis and can include/exclude an array of diagnoses. Direct visualization of LN tissue has diagnostic value in growing or persistent LNs with no accompanying signs or symptoms.

LNs with concerning features are commonly sampled or excised in the pediatric population [4]. Lymph node biopsy is necessary to facilitate the diagnosis of rare benign conditions such as sarcoidosis or histiocytosis [5]. Currently, complete lymphadenectomy in benign lymph node disease is necessary to cure atypical mycobacterial lymphadenitis as medical treatment is often prolonged with poor responsiveness [6]. Unexplained cervical lymphadenopathy poses a challenge to pediatricians and pediatric surgeons whether to monitor or excise [7].

The described cases represent a subset of non-tuberculous granulomatous lymphadenopathy of unknown cause. These cases did not respond to conservative measures and needed radical surgical excision to offer a cure.

Case 1

A twelve-year-old male, previously healthy, presented with a right neck mass that was first noted one week prior to the initial presentation. Careful history taking did not reveal any fever, cough, rhinorrhea, sore throat, Abstract Initial presentation with cervical lymphadenopathy poses a wide array of differential diagnoses and prognoses. We report four non-tuberculous granulomatous lymphadenitis cases with temporal and geographic clustering, unresponsive to medical management that warranted modified neck dissection to facilitate cure. To help recognize these atypical cases, we describe clinical and radiological features of this condition. We also present our experience with the management and the outcomes of this uncommon disease. In the span of one year (2016-2017), four patients aged 2 to 14 years with massively enlarged neck masses were referred for surgical evaluation. All patients warranted neck dissection and removal of pathological cervical lymph nodes (LN). Patient presentation, testing, treatments, and follow-up were reviewed. The neck masses ranged from 3 x 3 cm to 7 x 7 cm on physical exam with no accompanying infectious symptoms. Extensive testing did not reveal a diagnosis. Interestingly, all the four pathological analyses revealed granulomatosis with variable degrees of necrosis (focal to extensive). The follow-up revealed no evidence of recurrence in any of the patients. The patients with isolated massive granulomatous cervical lymphadenopathy not related to any known disease, infectious or malignant etiology, could be categorized under “Granulomatous Lymphadenopathy of Unknown Cause”. After exclusion of common causes of lymphadenitis in children, early consideration should be given for radical LN excision as is done in cases of atypical mycobacteria to ensure cure. nausea, vomiting, shortness of breath, chest pain, abdominal pain, dysuria, loss of appetite, and diarrhea. There was also no fatigue, weight loss, or night sweats. There was no recent travel– and his immunizations were up-to-date. He lived at home with his parents, a seven-year-old sister who was healthy, and a pet cat.

Amoxicillin-clavulanate was prescribed and after 10 days of antibiotics, the mass enlarged and spread to the left side of the neck. He was then brought to the emergency department for the same complaint. An ultrasound of the neck showed a right neck hypervascular LN of 3.5 x 3.4 x 1.1 cm and a left neck hypervascular LN of 2.1 x 1.8 x 0.6 cm. Computed tomography scan of the chest, abdomen, and pelvis did not reveal additional LNs or abnormalities. Laboratory studies including cytomegalovirus (CMV) and Ebstein-Barr virus (EBV) serology showed no significant abnormality other than elevated EBV Immunoglobulin G (IgG) levels (Table 1). Mono-spot test, sputum, blood, and urine cultures were negative. Physical exam revealed a right-sided 4 x 4 cm mildly tender LN, two smaller posterior cervical LNs, as well as a left-sided 2 x 2 cm LN.

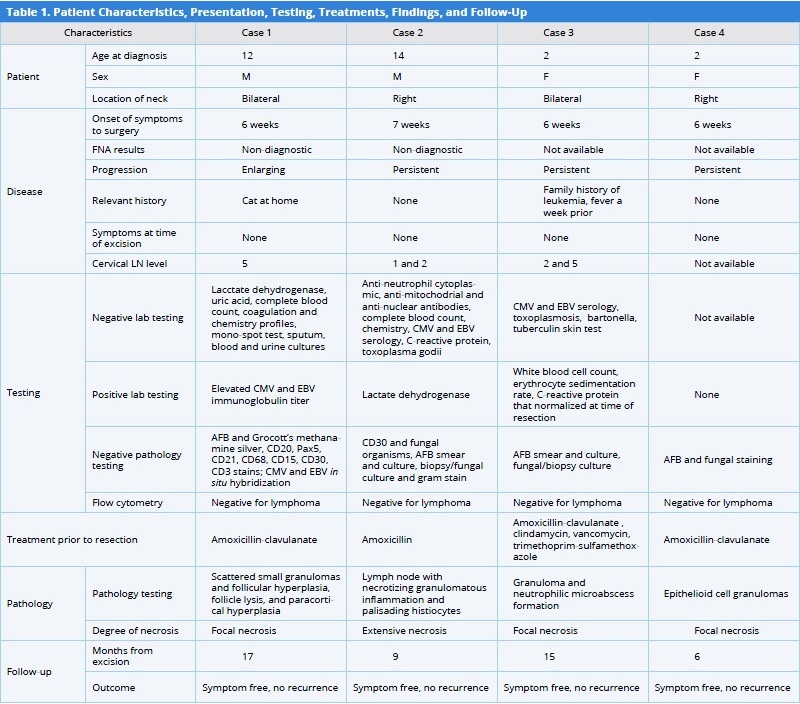

AFB, acid fast bacillus; CMV, cytomegalovirus; EBV, Ebstein-Barr virus; FNA, fine needle aspiration; LN, lymph node.

Four days later, he was admitted to the hospital for thorough workup of diffuse bilateral cervical lymphadenopathy. He was evaluated by oncology specialists who recommended fine needle aspiration (FNA). Cytology findings were suspicious of Hodgkin’s lymphoma. The specimen was analyzed by immunohistochemistry for CD30, CD20, PAX5, and CD15 by flow cytometry, which showed no evidence of B or T cell non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma. Given the oncologist’s high suspicion for lymphoma, a port was placed by the radiologist at the time of the FNA and chemotherapy was planned. However, as the flow cytometry did not confirm malignancy, he was referred for surgical evaluation. He underwent radical LN excision (Level 5). The specimens consisted of two tan-pink LNs (4 x 1.8 x 0.6 cm and 2.1 x 1.2 x 1 cm). The specimens were tested for acid fast bacillus (AFB) stain, CD20, PAX5, CD21, CD68, CD15, CD30, CD3, CMV, and EBV in situ hybridization and these tests excluded these infectious causes. Flow cytometry showed no evidence of T or B cell lymphoma. The overall impression of pathology report consisted of non-specific changes and supported a reactive process showing small scattered granulomas, areas of follicular hyperplasia and follicle lysis, paracortical hyperplasia, and focal necrosis.

The disease was monitored for three months with no recurrence. The central line with the port was removed. A 17-month follow-up revealed no recurrence of lymphadenopathy and no other symptoms.

Case 2

A fourteen-year-old male, previously healthy, developed right neck swelling for 6 weeks with no resolution despite receiving a 10-day course of amoxicillin. The patient denied any fever, night sweats, decreased appetite, fatigue, weight loss, sore throat, toothache, cough, and difficulty breathing or swallowing. On physical examination, there was a right neck swelling at levels 1 and 2; the swelling was non-tender, soft, and mobile with no apparent skin changes. FNA was non-diagnostic. Lab tests were within normal limits except for an elevated lactate dehydrogenase level (Table 1).

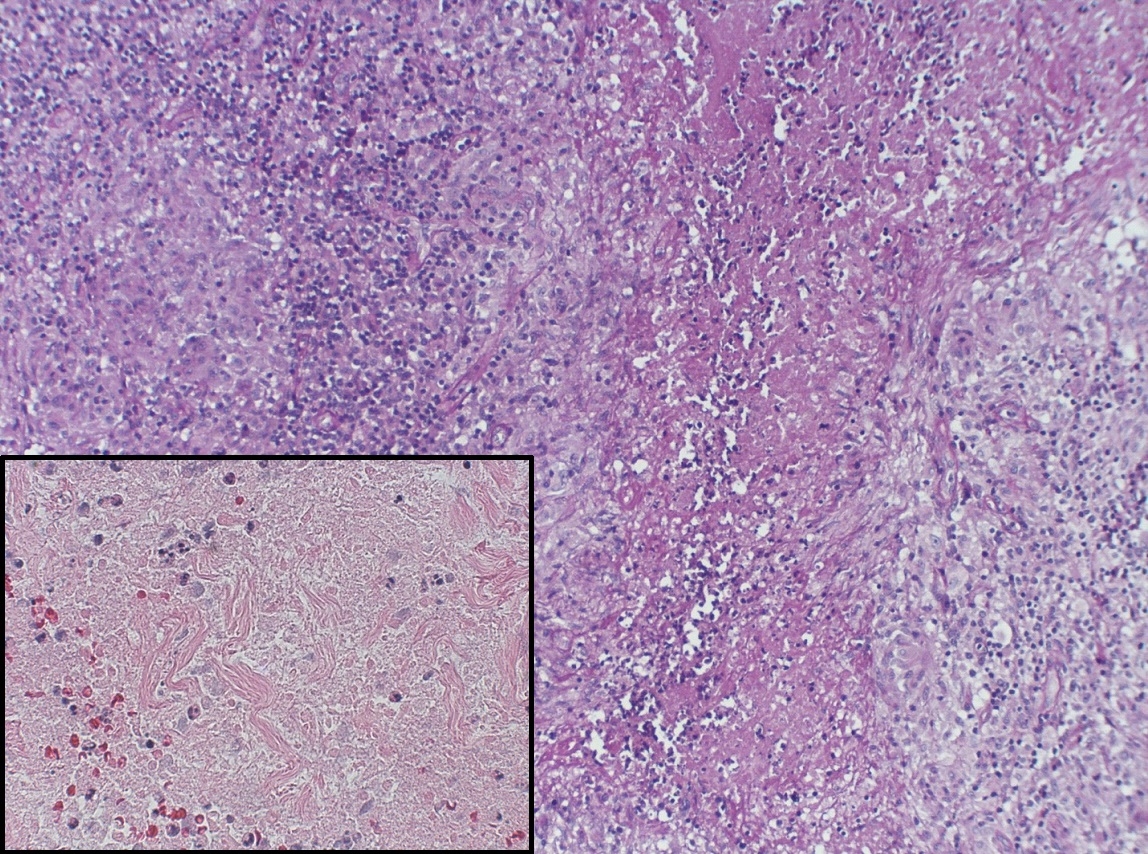

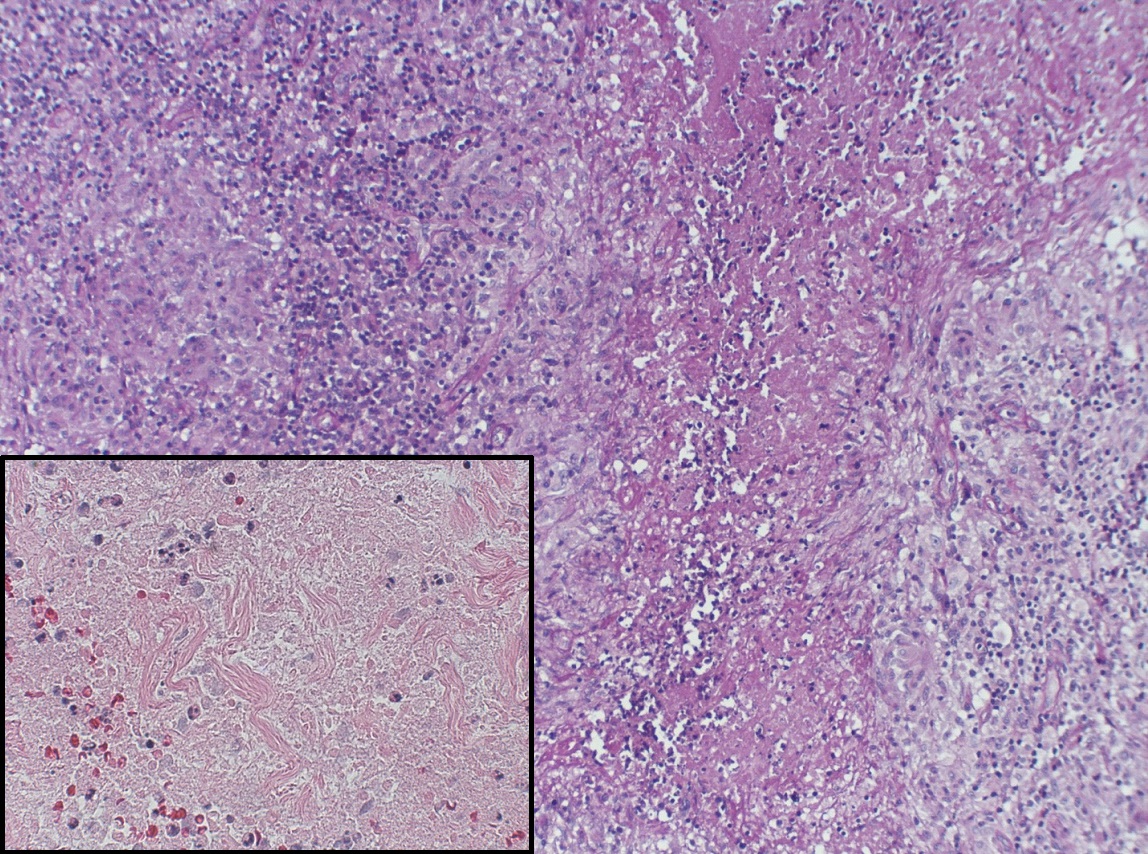

The patient underwent surgical excision. Intraoperatively, necrotic caseating material was encountered and also a 2.3 x 2 x 0.5 cm and a 2.3 x 1 x 0.3 cm red-yellow irregular soft tissue fragments. The pathological analysis showed LNs with necrotizing granulomatous inflammation with palisading histiocytes (Figure 1). Flow cytometry showed no evidence of lymphoma. The AFB smear and culture, specimen bacterial and fungal cultures, and gram stain were all negative. The patient had complete resolution of adenopathy after surgery with no recurrence over a nine-month follow-up.

Figure 1. Portion of right cervical lymph node (Case 2) showing necrotizing granulomatous inflammation and palisading histiocytes. Insert shows numerous cells with pyknotic nuclei; there is extensive karyorrhectic debris (hematoxylin and eosin stain x 100 magnification, insert x 400).

Case 3

A two-year-old female was brought to the emergency department for bilateral lymphadenopathy. Parents of the child reported that the left side of her neck was swollen for 6 days and spread to the contralateral side within one day (Figure 2). Swelling did not improve after three days of amoxicillin-clavulanate that was prescribed in the outpatient setting. There was no associated pain, cough, rash, vomiting, diarrhea, drooling, or shortness of breath. The patient was febrile one week prior to the onset of lymphadenopathy. The family history was significant for a maternal aunt who died due to leukemia at four years of age. The patient was admitted to the hospital for further workup that revealed elevated inflammatory markers (Table 1). Ultrasound of the neck showed multiple non-vascular bilateral cervical level 2 and 5 enlarged LNs, the largest 4.4 x 2.4 x 3.4 cm on the left and 3.1 x 1.7 x 2.8 cm on the right. CMV, Bartonella Henselae/Quintana, and Toxoplasma immunoglobulin M and immunoglobulin G levels were negative. In addition, film array (for viruses including respiratory syncytial virus, adenovirus, and coronavirus) and blood culture were also negative. Chest X-ray showed no pulmonary disease or masses. She was started on intravenous clindamycin and vancomycin during her hospital stay. She was afebrile and swelling was stable. Serial ultrasound of the neck showed stable, necrotic, and bilateral lymphadenopathy, and the acute phase reactant levels decreased. She was discharged home on oral trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole and clindamycin. Two weeks later, the redness and swelling of her LNs increased, which were drained and the specimen grew MSSA (Methicillin sensitive Staphylococcus Aureus) with no growth of mycobacterium or fungus. Once the antibiotic course was completed, bilateral modified neck dissection and LN resection were performed. The AFB smear and culture on the specimens were negative; the bacterial and fungal cultures were negative as well. Flow cytometry showed no immunophenotypic evidence of B or T cell non-Hodgkin lymphoma. Pathological findings showed acute lymphadenitis, necrotizing with prominent histiocytes accumulation, and neutrophilic micro-abscess formation. We suspected that the MSSA was a superinfection on an underlying process. In the recent 15-month follow-up, there was no evidence of recurrence.

Figure 2. Image of massive lymphadenopathy of the patient mentioned in Case 3.

Case 4

A two-year-old female presented with a right-sided neck mass that was enlarging after a five-day course of amoxicillin-clavulanate. There were no associated night sweats, fever, cough, ear infection, nausea, vomiting, and diarrhea. Physical examination revealed a 3 x 3 cm neck mass that was mobile and non-tender. The mass was persistent and the patient underwent LN excision six weeks after the onset of symptoms. The specimens showed epithelioid cell granulomas with focal necrosis; special stains for acid fast bacilli and fungi were negative. Follow-up at six months showed complete resolution and there was no recurrence of symptoms.

In this case series, four patients with significantly enlarged LNs that were either progressing or persisting for at least six weeks were referred for complete excision (Table 1). There was no obvious cause of lymphadenopathy or clear diagnosis at the time. All four cases were unexplained lymphadenopathies with progression and size that were concerning for malignancy. Additionally, the presence of lymphadenopathy in more than one cervical region furthered the suspicion for malignancy [7]. A recent study evaluating the benefit of FNA in pediatric lymphadenopathy with concerning features of duration > 2 weeks, size ≥ 1 cm if supraclavicular or ≥ 2 cm if axillary/inguinal, and the absence of accompanying signs, showed that in 10% of cases, surgical biopsy was necessary for definitive diagnosis of malignant disease [8]. Furthermore, the supraclavicular location of lymphadenopathy was associated with an increased risk of malignancy [4]. Although FNA is a safe and useful modality for the evaluation of pediatric lymphadenopathy, it may delay treatment in patients with high suspicion for malignancy. In our case series, all four patients were at very high risk for malignancy and in one patient, planning for chemotherapy was initiated, including port placement, by the radiologists in consultation with oncology. Early cervical LN excision in select patients would avoid treatment delays and unnecessary testing/ procedures, and could be curative in cases of atypical mycobacteria [9].

It is important to exclude rarer causes of lymphadenitis in children with a particular emphasis on history, physical examination, and immunological testing. Suspicion of cat scratch disease was present in Case 1, given the history of a pet cat at home. However, the patient did not have any accompanying symptoms and the physical examination did not reveal any skin lesions suspicious of an infected lesion with erythema or surrounding rash. Furthermore, the ultrasound findings were not characteristics of cat scratch disease as there was no adjacent fluid collection or evidence of a lobular or ovoid hypoechoic LN with a hyperechoic hilum [10]. Pathological testing did not raise concern for cat scratch disease, as there was no evidence of granuloma or micro-abscess formation with central necrosis [5]. A correct diagnosis will facilitate adequate pharmacotherapy after establishing the cause and help in preventing recurrence.

i’s disease (necrotizing histiocytic lymphadenitis of Fujimoto and Kikuchi) and Sarcoidosis can be excluded only after the biopsy. In Kikuchi’s disease, the common pathological findings include coagulative necrosis in the paracortical areas [11], histiocytes interspersed with immunoblasts [12], the absence of granulocytes and rare plasma cells, and the presence of plasmacytoid cells [13]. Histiocytosis was seen under microscopic examination of the specimens from Cases 2 and 3. Case 3 pathology report mentioned an abundance of neutrophilic micro-abscess formations. This is opposed to the prominent non-neutrophilic karyorrhexis and necrosis seen in Kikuchi’s disease [14], making this disease less likely. Case 2 pathology report described LN with necrotizing granulomatous inflammation and palisading histiocytes that were also not the characteristics of Kikuchi disease.

All our four patients had a necrotizing granulomatous process and tested negative for known causes of such pathology as Kikuchi’s disease, tuberculosis, sarcoidosis, or Cat Scratch disease. We propose a diagnosis of exclusion based on the geographic clustering of cases as ‘Granulomatous Lymphadenopathy of Unknown Cause’ after excluding other more common causes. These cases are unresponsive to standard pharmacotherapy and can progress rapidly to skin necrosis from pressure; they can also become superinfected and cause significant morbidity. Consideration for radical excision should be made early in cases of cervical lymphadenopathy not fitting into the current treatment algorithms [5]. Care should be taken during surgical resection to avoid injury to vital neurovascular structures that develop through the pathologically enlarged nodes with significant anatomic distortion.

Patients with isolated massive cervical lymphadenopathy with some degree of necrosis not related to any known disease and infectious or malignant etiology could be categorized under ‘Granulomatous Lymphadenopathy of Unknown Cause’. Pediatric patients with massive cervical lymphadenopathy may benefit from expedited testing and evaluation for adequate prevention of progression and recurrence of the disease. After a thorough evaluation by the infectious disease and oncology specialists, and exclusion of more common cases, early consideration should be given for radical LN excision as is done in cases of atypical mycobacteria to ensure cure in cases of massive cervical adenopathy. Further research is necessary to determine the causes of granulomatous lymphadenitis in children that do not fit into established clinical/pathological groups.

Received date: July 19, 2018

Accepted date: September 30, 2018

Published date: January 28, 2019

None

None

© 2019 The Author (s). This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (CC-BY).

The aim of the study was to characterize children with asymptomatic cervical lymphadenopathy including natural history, radiologic and pathologic findings, and provide guidance in diagnostic and therapeutic intervention and follow-up.

The authors present a case of a neonate born with an enlarging tongue mass whose biopsy revealed IMT with ALK positivity. Treatment included tumor debulking and an ALK inhibitor, crizotinib, which resulted in complete remission.

The authors describe their experience in treating severe recurrent respiratory papillomatosis with systemic bevacizumab in two young children with intractable papillomatosis requiring multiple surgical debridements. This is the first report to describe the successful management of recurrent respiratory papillomatosis with systemic bevacizumab in young children. The findings illustrate that systemic bevacizumab can have a dramatic effect on patient outcomes, eliminating the need for repeat surgical interventions. Furthermore, the findings suggest that this novel antiangiogenic agent can safely be used in young children using the same dosing recommendations used in the adolescent and adult populations.

This article presents a case study on the successful replantation of a pediatric lower lip after a dog bite, focusing on artery-only microanastomosis. It highlights the challenges and effective strategies in pediatric microvascular surgery, particularly emphasizing the importance of specialized surgical techniques and thorough postoperative care. Alongside the case study, an extensive literature review supports the feasibility of artery-only anastomosis and the traditional yet critical use of leech therapy for managing venous congestion. This research is vital for medical professionals specializing in pediatric surgery, offering key insights into improving both functional and aesthetic outcomes for young patients. Additionally, it identifies gaps in long-term research and stresses the need for ongoing studies to refine treatment protocols, making it an indispensable resource for enhancing patient care and outcomes in pediatric reconstructive surgeries.

This investigation delineates a pivotal association between socioeconomic inequities, quantified via the Area Deprivation Index (ADI), and an elevated incidence of button battery ingestion in pediatric populations, highlighting a profound public health issue. The results indicate that children residing in socioeconomically disadvantaged areas are at an increased risk of sustaining severe injuries from the ingestion of button batteries, which could lead to elevated morbidity and mortality rates. The study urgently calls for immediate diagnostic and therapeutic interventions to avert critical health complications and delineates the complex pathophysiology underlying button battery injuries. For clinicians and healthcare practitioners, particularly those within pediatrics and emergency medicine, this manuscript is indispensable. It provides deep insights into the ramifications of socioeconomic disparities on health outcomes, fosters the refinement of diagnostic and therapeutic modalities, and champions preventive initiatives. The authors advocate for intensified parental awareness, the redesign of battery products to enhance safety, and the formulation of healthcare policies that promote equity, aiming to curtail this escalating health challenge.

Obeid JM, Bongu SR, Burjonrappa SC. Large non-infectious granulomatous adenitis in children needs surgical excision for cure. Arch Otorhinolaryngol Head Neck Surg 2019;3(1):2. https://doi.org/10.24983/scitemed.aohns.2019.00096