Cholesteatomas of mastoid origin often grow silently, remaining unidentified and untreated for years. Cholesteatomas may not even be detected until they are quite massive, and diagnosis may only occur as a result of incidental imaging. Here, we report a case involving a 59-year-old man with delayed presentation of a huge mastoid cholesteatoma complicated by skull base erosion and cerebrospinal fluid leakage. Regular otologic, audiologic, and imaging examinations are the best strategies to avoid undesirable consequences related to chronic otitis media with cholesteatoma. Early recognition of this rare comorbid condition is essential because appropriate and timely treatment can prevent it from becoming fatal.

Cholesteatoma is defined as an accumulation of exfoliated keratin produced from stratified squamous epithelium in the middle ear without a previous history of ear infection, head trauma, or ear surgery [1,2]. The dysregulation of cell growth control with local invasive characteristics is the major mechanism underlying widespread structural destruction in the middle ear cleft. The goal of treatment is typically complete disease eradication. Given the fatal capacity of intracranial complications, cholesteatoma remains a risk factor of morbidity and mortality in areas where access to appropriate medical care may be limited [3]. Thanks to advances in diagnostic procedures, antibiotic therapies, and surgical techniques, huge cholesteatomas are rarely encountered. Here, we report an exceptional case of a patient with delayed presentation of a massive cholesteatoma complicated by skull base erosion and cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) leakage. It is very likely that few contemporary otologists have encountered this type of case.

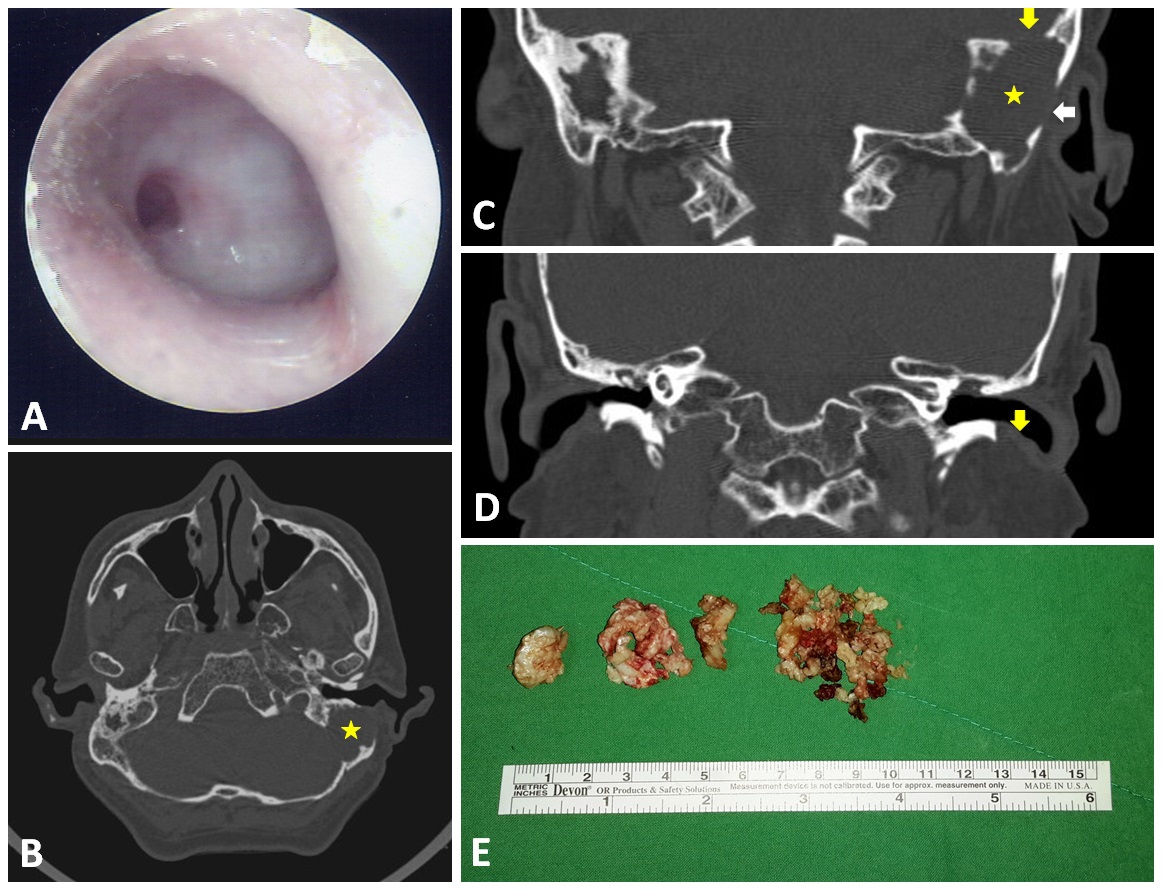

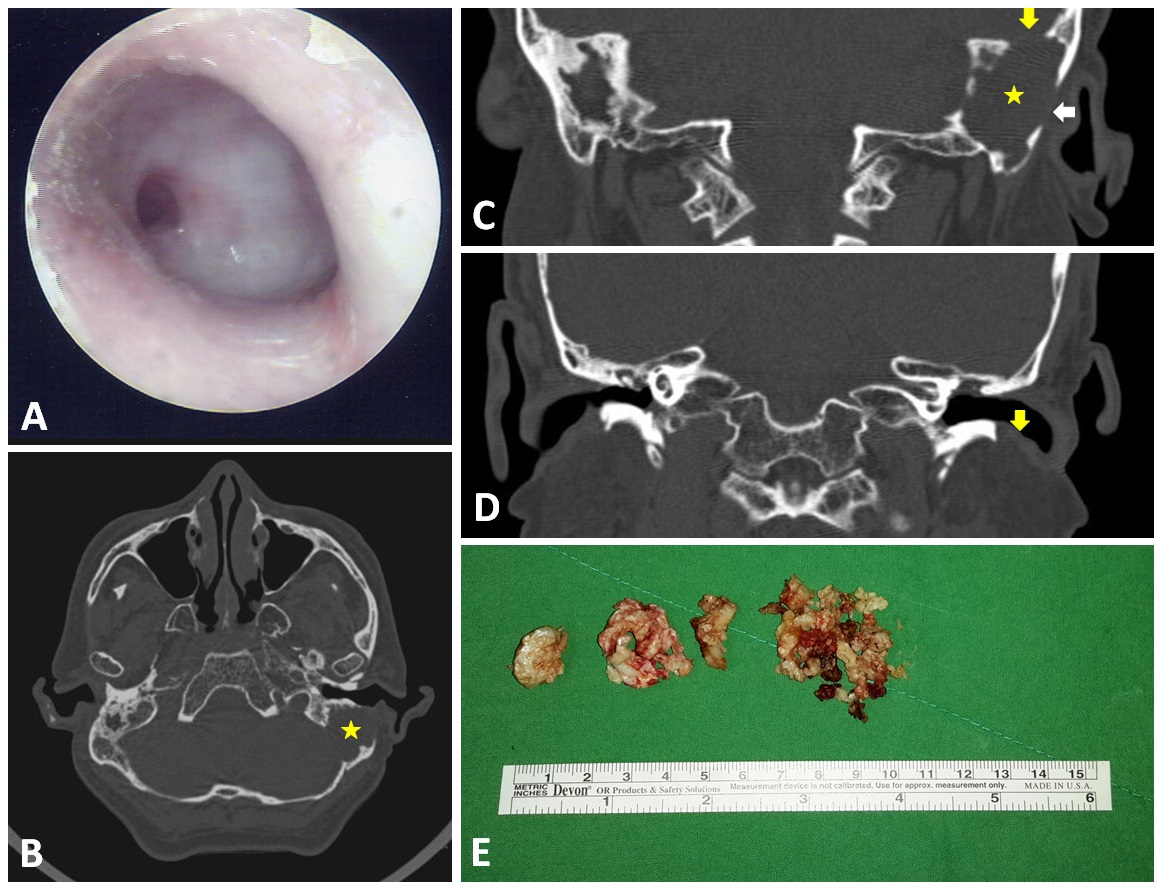

A 59-year-old man presented with recent hearing deterioration. He had a history of chronic otitis media in both ears and had suffered from occasional ear discharge since childhood. Despite the fact that local medical practitioners had referred the patient to otologists in tertiary hospitals, he refused these visits due to personal reasons. The patient had no other notable medical history, including no headache, vertigo, or otalgia. An otoscopic examination of both ears revealed total perforation of the tympanic membrane. Furthermore, thick granulation with a central hole on the left side covered the entire middle ear (Figure 1A); however, there were no signs of nystagmus or fistula, and the remainder of the neurological examination was non-contributory. Nonetheless, a hearing test revealed severe bilateral mixed hearing loss at all frequencies, and a CT scan revealed a huge soft tissue mass in the mastoid of the left ear (asterisk in Figures 1B and 1C) as well as bony defects in the skull base (yellowish arrow in Figure 1C), lateral mastoid cortex (whitish arrow in Figure 1C), and external ear canal wall (yellowish arrow in Figure 1D).

Figure 1. Otoscopy results showing total perforation of the left eardrum with thick granulation covering the middle ear (A). CT scan results revealed a huge soft tissue mass in the left ear mastoid (asterix in panel B and C) as well as bony defects at the skull base (yellowish arrow in panel C), in the lateral mastoid cortex (whitish arrow in panel C), and in the external ear canal wall (yellowish arrow in panel D). The huge mastoid cholesteatoma was removed piece by piece (E).

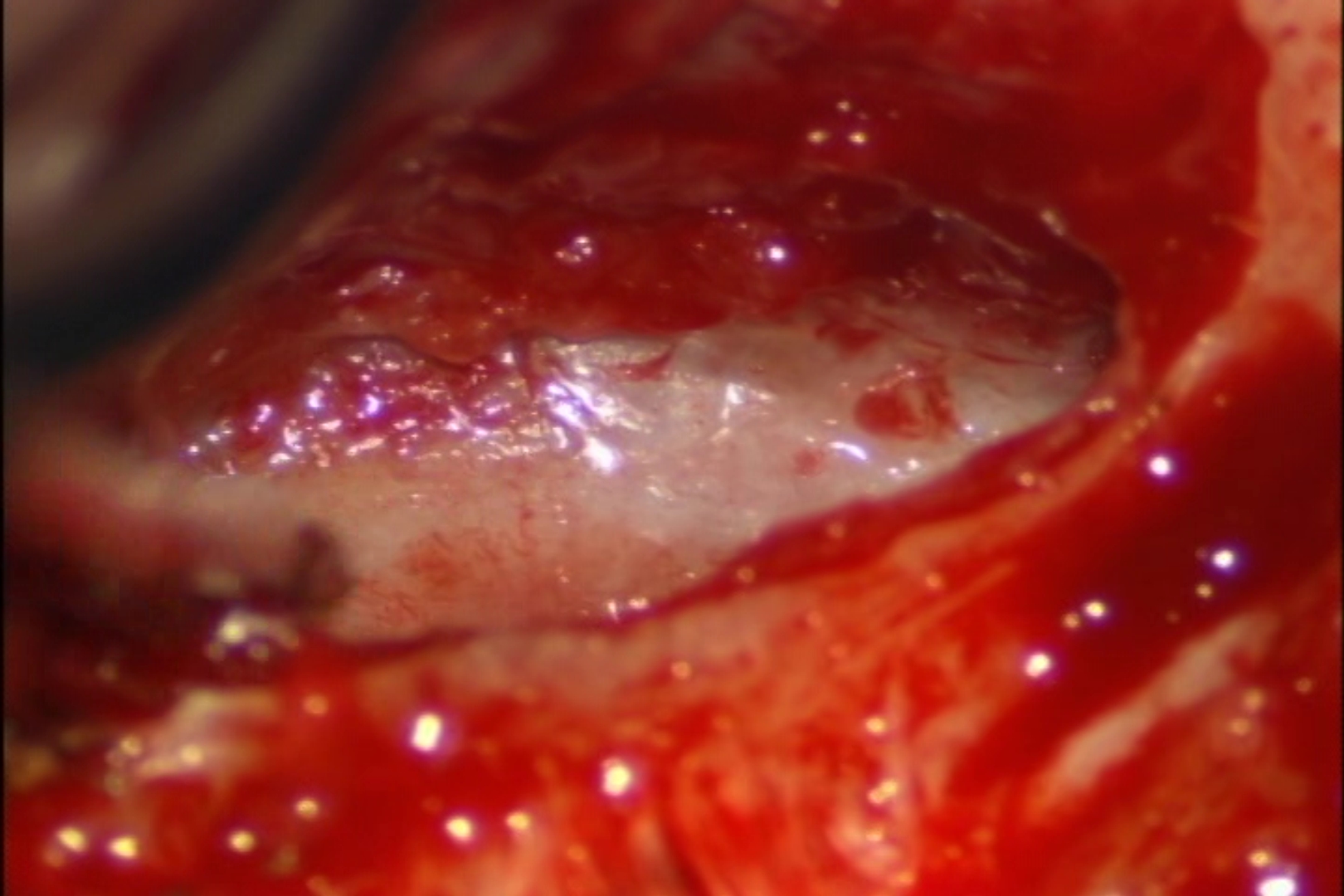

Surgical exploration and a subsequent histopathology examination revealed a huge cholesteatoma (Figure 1E and Video 1) tightly adhered to the outer dura of the left posterior cranial fossa (Figure 2). An extensive mastoidectomy (involving the external ear canal and epitympanum) was performed to define the magnitude of the cholesteatoma. In so doing, we also determined that the middle ear was filled with thick granulation tissue. Following the mastoidectomy, we initiated removal of the cholesteatoma piece by piece; however, persistent CSF leakage was identified during this procedure. This complication was rectified by grafting a commercially available collagen matrix graft over the leak (DuraGen® Plus). The defect in the posterior cranial fossa was restored using pieces of cartilage, which was then reinforced by overlaying gelform. Third generation cephalosporin antibiotics were used to prevent post-operative infection. Second-look surgery (3 months after the initial operation) revealed residual cholesteatoma, which was subsequently removed. The patient presented no post-operative intracranial complications. During three years of follow-up, no recidivism was observed in otoscopic, CT scan, or diffusion-weighted MRI examinations.

Figure 2. Skull base defect with exposure of posterior fossa dura.

Video 1. Surgical exploration revealed a huge cholesteatoma complicated by skull base defects, exposure of posterior fossa dura, and CSF leakage.

Despite the fact that surgical intervention is a mainstay of cholesteatoma treatment, not all patients are good candidates for surgery. For example, pre-existing conditions, such as a history of heart failure, certain types of blood dyscrasias, or weakness due to old age or pregnancy, can prevent or postpone surgical interventions. Furthermore, eligible patients may have personal reasons for choosing to forgo surgery. To control the disease and thereby avoid severe complications, patients should undergo regular otologic examinations, receive audiologic follow-ups, and have crusts debrided.

Nonetheless, patients who require repeated aural toilets may have difficulty obtaining the treatment they need. This is particularly true for children and inhabitants of rural areas lacking easy access to health clinics. A failure to attend follow-up appointments can have negative consequences on patient health. Furthermore, the absence of severe symptoms associated with inflammation or infection (e.g., otalgia, vertigo, or headache) may create a false sense of security among patients, leading to them the erroneous conclusion that follow-up appointments are not necessary. Missed follow-ups can result in delayed or missed diagnoses and potentially lead to serious complications and/or life-threatening infections. Indeed, this was the case with the 59-year old cholesteatoma patient reported here.

Mechanisms of Cholesteatoma-induced Bone Destruction

Bones are sometimes reabsorbed into the cholesteatoma via osteoclastogenesis. Several cytokines, including interleukin (IL)-1, IL-6, IL-17, interferon-beta, and parathyroid-hormone-related protein (PTHrP), which are up-regulated in the cholesteatoma, stimulate osteoclastogenesis via direct or indirect effects on osteoclasts [4,5]. Moreover, the receptor activator of the nuclear factor kappa-B ligand (RANKL) is an osteoclast differentiation factor and a key osteoimmune regulator of bone physiology and pathology [6]. Osteoprotegerin (OPG) is a soluble decoy receptor for RANKL, which inhibits osteoclast formation by interrupting the interaction between RANKL and its membrane-bound receptor (RANK). The involvement of the RANKL/OPG/RANK axis in cholesteatoma-induced bone remodeling has been recognized [7].

Researchers have been exploring the significance of chemical lysis in bone destruction associated with cholesteatoma since the 1950s [8]. This research has determined that many proteolytic enzymes can cause bone destruction and promote disease aggressiveness [5]. For example, matrix-metalloproteinases (MMPs) are important proteolytic enzymes that cause the destruction of bony tissue. The up-regulated expression of MMP (e.g., of MMP1, MMP9, MMP10, and MMP12) and the down-regulated expression of associated enzyme inhibitors (tissue inhibitor of metalloproteinases, TIMP) can degrade the extracellular matrix [5,9]. The large number of metalloproteinases found in children may partly explain why pediatric cholesteatomas tend to be more aggressive than their adult counterparts [10,11].

Recent breakthroughs suggest that acids derived from products of aerobic (e.g., Staphylococcus aureus and Proteus species) and anaerobic (e.g., Peptococcus and Bacteroides species) microorganisms may stimulate bone destruction associated with cholesteatoma [12-14]. Myeloperoxidase (MPO) is a hemeprotein and the key constituent of neutrophil azurophilic granules. MPO is capable of producing hypohalous acids with antimicrobial activities [5,15,16], and increased MPO expression is associated with the cholesteatoma-related destruction of bone [5,16]. High concentrations of the bacterial lipopolysaccharides (LPS) associated with prolonged inflammation may evoke MPO activity in cholesteatomas [16]. These observations suggest that infections play a critical role in cholesteatoma-induced bone destruction.

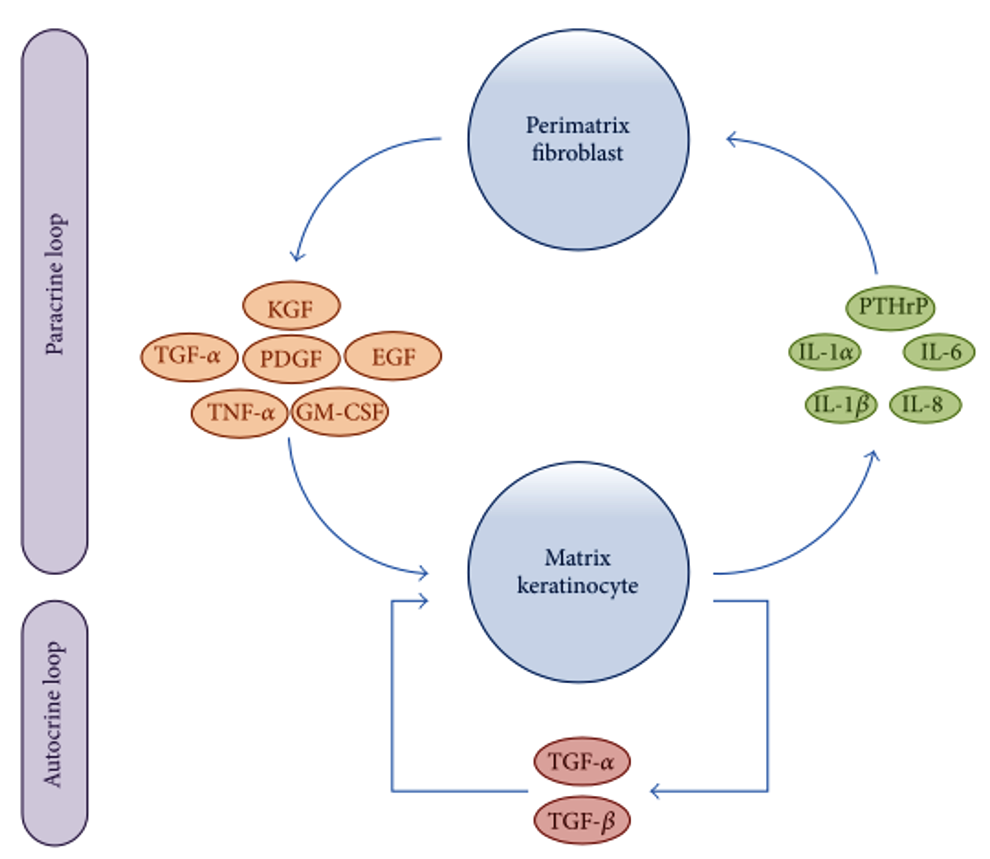

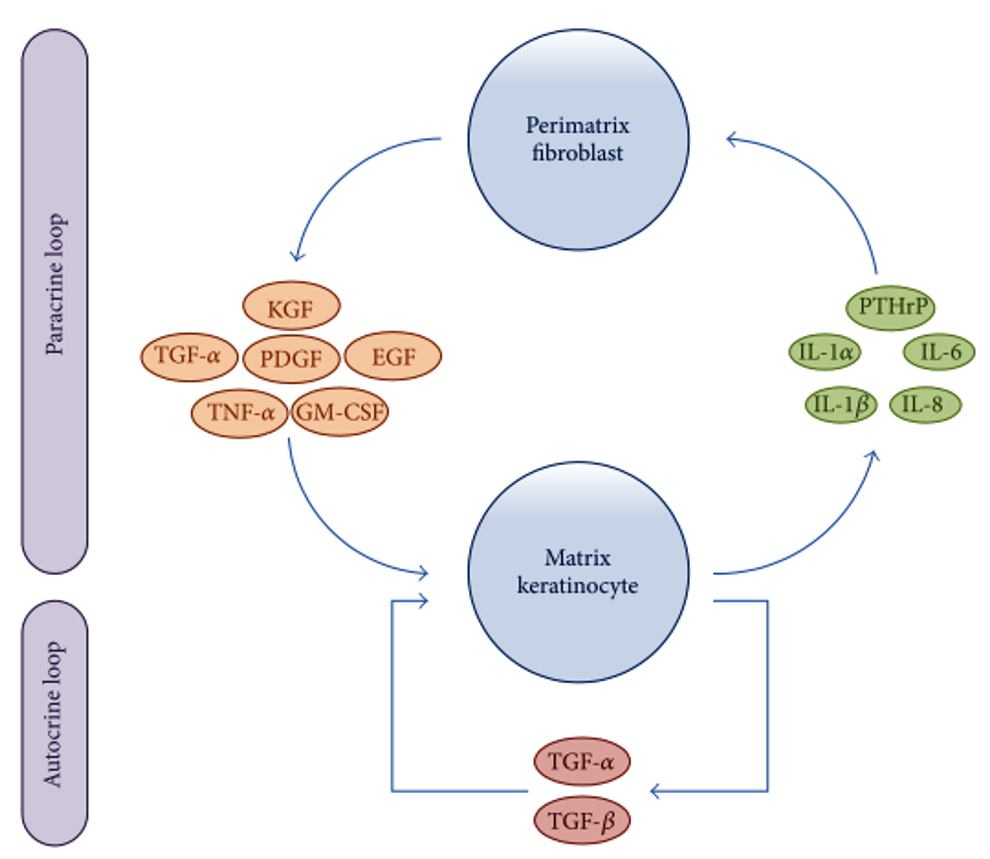

Researchers have been attempting to delineate the precise molecular and cellular dysfunctions involved in the pathogenesis of cholesteatomas. Recent advances in immunohistochemical analysis have revealed that interactions between matrix keratinocytes and perimatrix fibroblasts play an important role in the processes of homeostasis and tissue regeneration after inflammation. Furthermore, the over-reaction of host immune response to inflammation via autocrine and paracrine signaling has recently been associated with the progression of cholesteatoma. As shown in Figure 3, matrix keratinocytes secrete PTHrPs and pro-inflammatory cytokines, such as IL-1α, IL-1β, IL-6, and IL-8. These keratinocyte-derived cytokines induce perimatrix fibroblasts to secrete several other cytokines, such as keratinocyte growth factor (KGF), granulocyte macrophage-colony stimulating factor (GM-CSF), epidermal growth factor (EGF), tumor necrosis factor-alpha (TNF-α), platelet-derived growth factor (PDGF), and TGF-α. These fibroblast-derived cytokines in turn induce the differentiation, proliferation, and migration of matrix keratinocytes. In a form of autocrine signaling, TGF-α and TGF-β are constitutively expressed in hyperproliferative epithelium, regulating keratinocyte proliferation and differentiation [5].

Figure 3. Schematic representation showing paracrine and autocrine interactions between matrix keratinocytes and perimatrix fibroblasts. EGF, epidermal growth factor; GM-CSF, granulocyte macrophage-colony stimulating factor; IL, interleukin; KGF, keratinocyte growth factor; PDGF, platelet-derived growth factor PTHrPs; matrix keratinocytes secrete parathyroid-hormone-related proteins; TGF, transforming growth factor; TNF, tumor necrosis factor.

Management of CSF Leaks

Bony erosion of the posterior cranial fossa with dural exposure and CSF leakage is a serious complication of cholesteatomas. Dural defects can be rectified using biological (e.g., temporalis fascia, pericranium, fascia lata, fat, muscle, bone, and cartilage) and alloplastic (non-biological, e.g., silicon, oxycel cotton, bone wax, and fibrin glue) materials [17]. The techniques involved in the rectification process involve single-layer and multi-layer leak closures; however, multilayer techniques have shown higher success rates (i.e., 2-year closure rate: 100% for the multilayer technique versus 75.4% for the single-layer technique) [18]. In the case reported here, the CSF leak was rectified by combining a primary sealing material (DuraGen® Plus) with additional pieces of cartilage and gelform for reinforcement. The three-year post-operative follow-up period was uneventful.

The fact that persistent cholesteatomas in the mastoid may produce only subtle symptoms means that the diagnosis of this condition may be delayed until mid- to late-adulthood. Delayed presentation of a huge mastoid cholesteatoma with skull base erosion and CSF leakage can have negative health consequences for patients. Regular otologic examinations, audiologic follow-up, and imaging examinations are viewed as the most effective strategies for the prevention of this type of situation. Early recognition of cholesteatomas is essential, as appropriate and timely treatment can prevent this rare comorbid condition from becoming fatal.

Received date: June 09, 2020

Accepted date: July 28, 2020

Published date: August 31, 2020

The study is in accordance with the ethical standards of the 1964 Helsinki declaration and its later amendments or comparable ethical standards.

This study was sponsored by grants from Medical Affairs Bureau Ministry of National Defense (MAB-107-099) and Taoyuan Armed Forces General Hospital (AFTYGH No. 10507, AFTYGH No. 10626, and AFTYGH No. 10734).

The author reports no financial or other conflict of interest relevant to this article, which is the intellectual property of the author.

The article has been published in a preprint version (Preprint Archives of Clinical Images & Videos 2017;1[1]:2), including the legends that have not been peer-reviewed.

© 2020 The Author. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (CC-BY).

Video 1. Surgical exploration revealed a huge cholesteatoma complicated by skull base defects, exposure of posterior fossa dura, and CSF leakage.

The present study demonstrated that TEES could be a satisfying alternative to traditional microscopic surgery for the management of congenital cholesteatoma, even in pediatric patients. However, one-handed surgery demands greater skill and requires more practice to achieve a good outcome.

Authors reported a case of cholesteatoma that mimicked facial neurinoma. To avoid confusion in such cases, diffusion-weighted MRI may be useful in preoper-ative differential diagnosis.

Newly discovered epidemiological evidence linking cholesteatoma to depression suggests that routine screening and monitoring of psychological status among cholesteatoma patients is warranted. Policies aimed at the early detection and timely treatment of comorbid depression following diagnosis with cholesteatoma could enhance health promotion and disease prevention.

The authors report a case of otogenic Lemierre's syndrome in a male patient who presented with atypical symptoms and was subsequently treated aggressively with antibiotics and surgery. In this article, the authors demonstrate how they could have avoided serious complications by diagnosing and treating the patient earlier. The authors suggest key points that should be noted in clinical practice in order to prevent misdiagnosis or delayed diagnosis of Lemierre's syndrome.

The authors describe a 41-year-old man who suffered retraction-related complications that may have been missed or delayed. The present case illustrates the potential dangers associated with tympanic retraction pockets, despite the fact that their bottoms are clear and clean. The article discusses the reasons for the lack of consensus among otologists regarding the appropriate way to treat tympanic membrane retractions. There is further discussion regarding the challenges associated with early surgical intervention.

This study investigates the efficacy of conservative management using 5-fluorouracil (5-FU) for treating cholesteatoma in ambulatory care settings, offering an alternative for patients who prefer to avoid surgery. Over 13 years, 15 ears of 14 patients were treated with a 5% 5-FU cream and assessed using Takahashi's efficacy criteria. The results revealed positive outcomes, with 87% of cases deemed good and 13% as fair, with no poor evaluations. This approach may be suitable for specific populations, such as older adults and individuals in remote areas with limited access to specialized healthcare services.

The incidence of high-grade sinonasal adenocarcinomas of non-intestinal origin is extremely rare. In this case report, the authors present a very rare case of high-grade non-intestinal sinonasal adenocarcinoma presenting with a challenging diagnosis. Because of its significantly different prognosis, this study provides a detailed explanation of how the authors differentiate it from other sinonasal tumors. In addition, they describe how a radical endoscopic resection was applied in order to achieve a total excision.

Kuo CL. Dangers of a false sense of security in a huge mastoid cholesteatoma with skull base erosion and cerebrospinal fluid leakage. Arch Otorhinolaryngol Head Neck Surg 2020;4(2):5. https://doi.org/10.24983/scitemed.aohns.2020.00134