Lemierre’s syndrome is a septic thrombophlebitis of the internal jugular vein and is often associated with oropharyngeal infections caused by Fusobacterium necrophorum. Otogenic Lemierre's syndrome has been reported to occur in the pediatric population, though such cases in adults are rare. In this report we describe a 27-year-old Bangladeshi male who presented to the emergency department with fever and cough for two days. He was febrile, hypotensive, tachycardic, and suffering from respiratory distress, which necessitated intubation and inotropes in the intensive care unit. Leukocytosis, an increased C-reactive protein marker, and thrombocytopenia were present. The blood cultures grew Enterococcus casseliflavus and Enterococcus raffinosus. To locate a gastrointestinal source, abdominal and pelvic computed tomography was performed, but the results were inconclusive. An enoxaparin treatment was initiated following a left internal jugular vein thrombosis detected during central line placement. Upon recurrence of spiking fevers, a computed tomography of the neck was performed, which demonstrated opacification of the left mastoid. An otoscopy revealed an external auditory canal purulence with grade 3 attic retraction. An audiogram revealed moderate to severe mixed hearing loss on the left side and type B tympanogram. The computed tomography and magnetic resonance imaging of the temporal bone revealed a left cholesteatoma with sigmoid sinus dehiscence, as well as gas locule formation in the sigmoid sinus and internal jugular vein. He had a left modified radical mastoidectomy in which the cholesteatoma was evacuated, the granulation around the sigmoid sinus was removed, and the pus around the sigmoid sinus was drained. His recovery was uneventful. In summary, the diagnosis of otogenic Lemierre's syndrome requires a high index of suspicion, particularly in obtunded patients, or in cases where language barriers obstruct detailed symptom assessment. The presence of internal jugular vein thrombosis should prompt further evaluation of the head and neck region for possible sources of infection.

Lemierre’s syndrome manifests as thrombophlebitis of the internal jugular vein caused by anaerobic bacteria, particularly Fusobacterium necrophorum [1]. In general, Lemierre's syndrome occurs following oropharyngeal infections, while cases of otogenic Lemierre's syndrome precipitated by acute otitis media and mastoiditis have been reported in pediatric patients [2], but such cases are rare in adults. Lemierre's syndrome can also be a life-threatening condition owing to the possibility of metastatic infection affecting many organ systems and the consequential risk of severe sepsis [3]. Our case report describes an adult with otogenic Lemierre's syndrome complicated by metastatic severe bilateral pneumonia presenting with atypical symptoms and requiring aggressive surgical and antibiotic treatment.

A 27-year-old Bangladeshi male presented with a 2-day history of productive cough, fever, pleuritic chest pain, and dyspnea. The patient was febrile (body temperature of 38.3°C) and hypotensive (systolic blood pressure of 90 mmHg), tachycardic (a heart rate of 120–130 beats per minute) and suffering from respiratory distress (a respiration rate of 30–35 breaths per minute). His blood analysis indicated leukocytosis (white blood cell count of 22.1 x 109/L), an elevated C-reactive protein level (206 mg/L), thrombocytopenia (platelet count of 25 x 109/L) and Type 1 respiratory failure (arterial blood gas). An X-ray of the chest showed bilateral lower zone opacities indicative of pneumonia. Prophylactic endotracheal intubation and inotropic support were required for septic shock, and he was transferred to the intensive care unit.

Following initial blood culture results showing Enterococcus casseliflavus and Enterococcus raffinosus, empirical Meropenem and oral Doxycycline were replaced with Imipenem and Daptomycin. Computed tomography scans of the abdomen, pelvis, and thorax revealed extensive consolidative ground glass changes in the bilateral lower lung fields that were consistent with severe bilateral pneumonia. However, other possible septic foci were not found. There was no evidence of infective endocarditis on a transthoracic echocardiogram. During the insertion of the central line, an incidental left internal jugular vein thrombosis was noted; therefore, therapeutic anticoagulation with subcutaneous Enoxaparin was initiated.

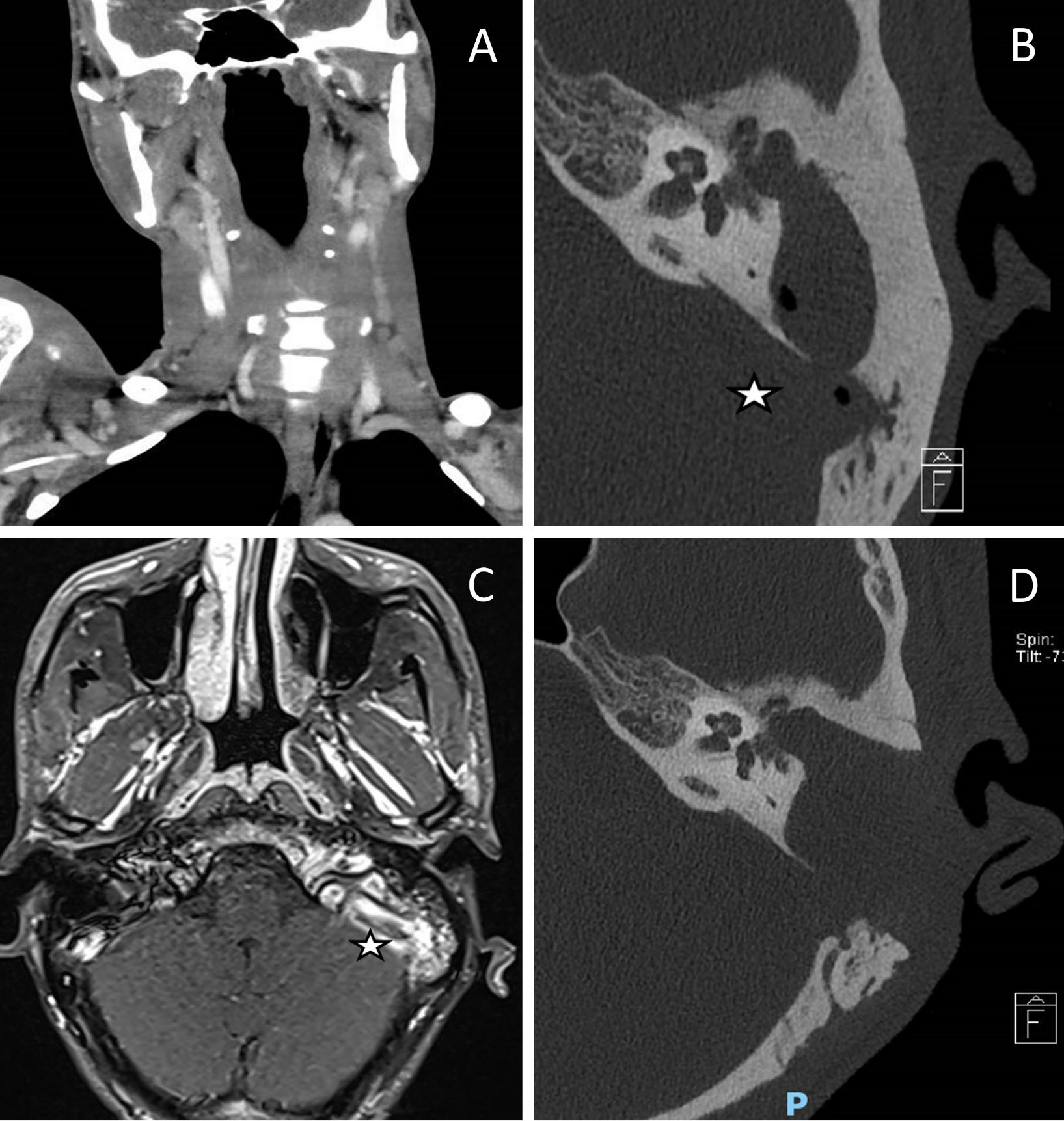

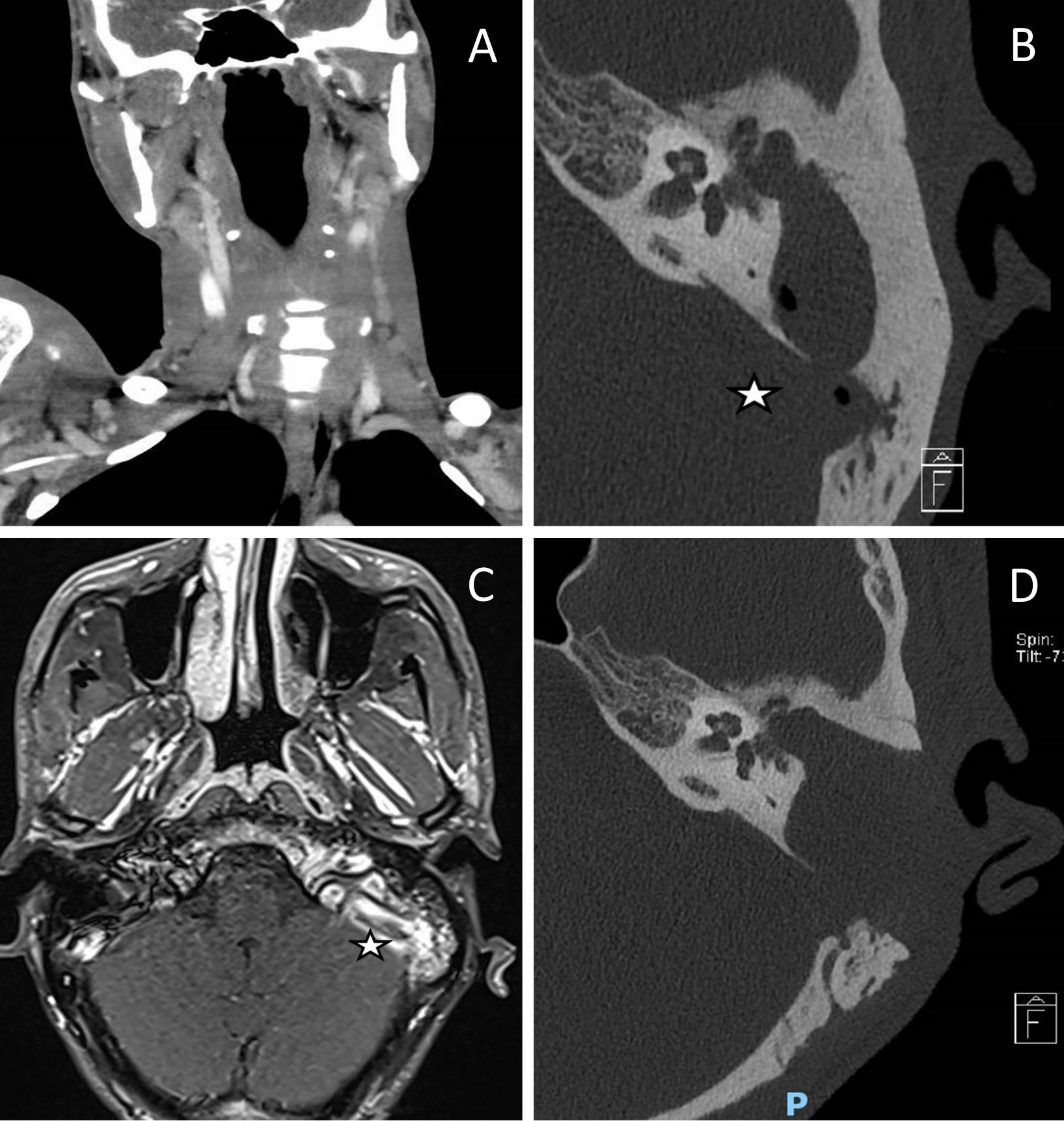

Persistent intractable fever despite 9 days of culture-directed antibiotics prompted repeat blood cultures which grew pan-sensitive Proteus mirabilis. A subsequent examination of the full body included a computed tomography of the neck, which revealed a left mastoid opacification in conjunction with an ipsilateral filling defect in the internal jugular vein, indicating venous thrombosis (Figure 1A).

Figure 1. Preoperative and postoperative images. (A) A computed tomography scan of the neck demonstrates an internal jugular vein thrombosis with a filling defect on the left side. (B) A computed tomography of the temporal bone reveals a cholesteatoma in the left middle ear along with a gas locule in the sigmoid sinus (indicated by the star). (C) There was no venous flow on magnetic resonance venography of the dural venous sinuses, indicating thrombosis of the left jugular bulb and the sigmoid sinus (labelled with a star). (D) Obtaining a computed tomography image of the temporal bone postoperatively demonstrates the complete removal of the left middle ear cholesteatoma and the disappearance of gas within the sigmoid sinus.

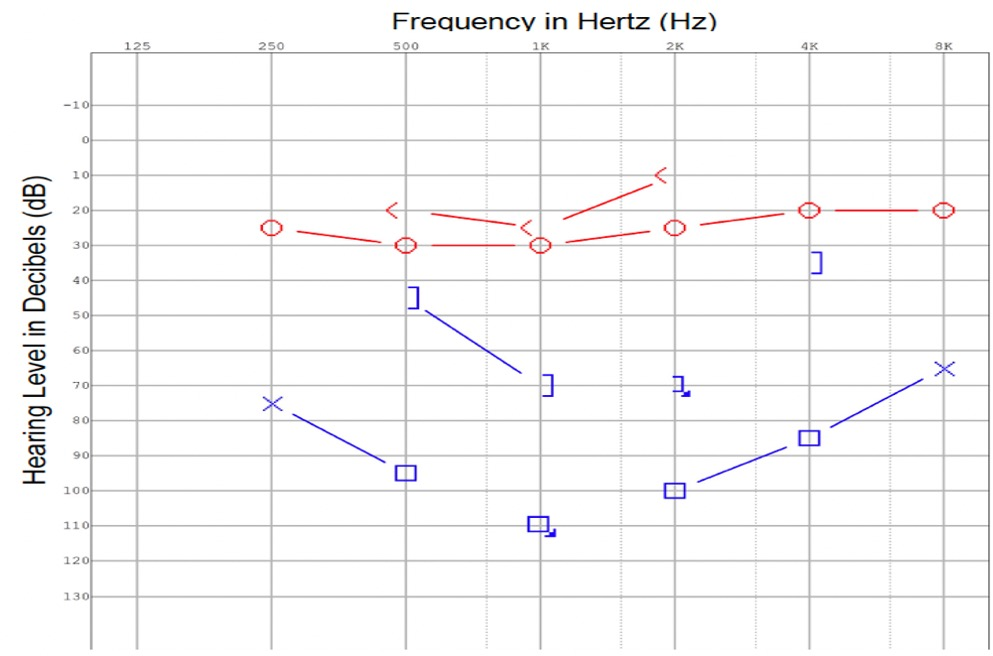

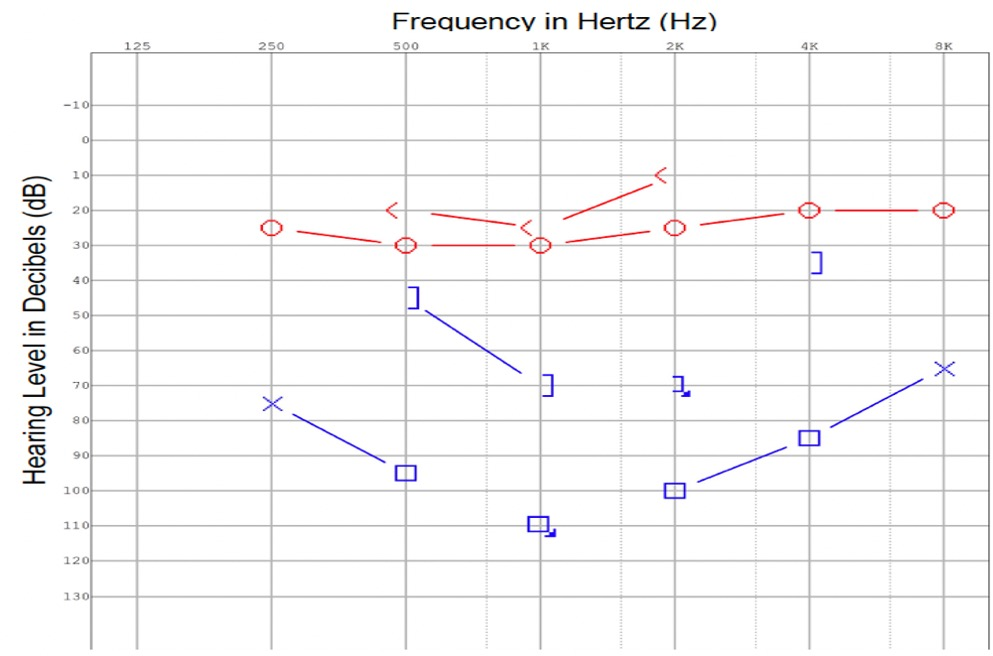

Extubation was completed and the patient was transferred to the general ward. An examination by the otolaryngology team revealed that the patient had chronic intermittent left otalgia, otorrhea, and a long-standing hearing loss on the left. There was no history of giddiness or disequilibrium. An otoscopic examination revealed purulent discharge from the left external auditory canal and grade 3 pars flaccida retraction of the eardrum without squames. Despite being opaque, the pars tensa of the eardrum remained intact. The post-auricular region did not exhibit subcutaneous edema (negative Griesinger's sign). A complete neuro-otologic examination did not reveal any abnormal findings. In the pure tone audiometry study, a moderate-to-severe mixed hearing loss was detected on the left side (Figure 2). In the tympanometry study, the left tympanogram was of type B. An aerobic ear canal swab was found to grow pan-sensitive Pseudomonas aeruginosa and Bacteroides fragilis.

Figure 2. At the time of diagnosis, a pure tone audiogram reveals a moderate to severe mixed hearing loss in the left ear.

This patient underwent urgent computed tomography of the temporal bone, which revealed opacification of soft tissue in the left middle ear along with extensive erosions of the left ossicular chain, tegmen tympani, and sigmoid plate, suggesting cholesteatoma with coalescent mastoiditis (Figure 1B). Additionally, the thinned bone overlying the mastoid facial nerve canal indicated the presence of dehiscence. There were also gas locules within the sigmoid sinus (Figure 1B). Additional imaging with magnetic resonance imaging of the head revealed that there was a left cholesteatoma without any encephalocele, however, there was a reactive enhancement of the facial nerve. The absence of venous flow on magnetic resonance venography of the dural venous sinuses indicated thrombosis of the left jugular bulb and sigmoid sinus (Figure 1C).

The patient underwent an urgent left modified radical mastoidectomy and meatoplasty. A large middle ear cholesteatoma was discovered intraoperatively, which extended posteriorly into the mastoid antrum (Figure 3A). It was observed that extensive granulation tissue surrounded the suprastructure of the stapes, along with erosion of the malleus head and the incus. The tegmen mastoideum was found to be eroded with a dehiscent mastoid facial nerve segment. Along the course of this nerve, there was a stimulation response of 0.8 mA. The sigmoid sinus plate was extensively eroded by cholesteatoma, with granulation observed on the edematous wall of the sinus (Figure 3B). The thrombus was palpable within the sigmoid sinus, despite pulsations being felt proximally. Purulence was evident in the peri-sigmoid region (Figure 3C).

Figure 3. Images obtained during surgery. (A) A cholesteatoma is present in the left middle ear (labelled with a letter C), as well as a tegmen mastoideum defect and the exposed dura (indicated with a letter D). (B) A sigmoid sinus that has been exposed (marked with a letter S), while granulations have been removed from the peri-sigmoid area. (C) Purulence in the sigmoid sinus (indicated with a letter S) observed during instrumentation of the peri-sigmoid region (marked with a star).

After the surgery, the patient recovered well without developing wound infections, facial palsy, or dizziness. The intraoperative tissue cultures grew Proteus mirabilis, Pseudomonas aeruginosa, and Enterococcus raffinosus. Histological analysis confirmed the diagnosis of cholesteatoma. The postoperative computed tomography imaging of the temporal bone showed complete clearance of the cholesteatoma, with no residual collections or gas locules (Figure 1D). The C-reactive protein and leukocyte counts were normal following surgery. After surgery, the patient was treated with culture directed Cefepime and oral Metronidazole for two weeks. In addition, he developed peripherally inserted central catheter-related thrombosis of the right arm, which required its removal. Cultures of peripherally inserted central catheter tips were negative.

On discharge from the hospital, his antibiotics were replaced with oral linezolid and ciprofloxacin, and his anticoagulant was replaced with Rivaroxaban. He was followed up outpatient for two months following discharge, completed his antibiotic therapy and recovered without complications.

The diagnosis of Lemierre's syndrome usually requires a history of recent head and neck infections (e.g., tonsillitis and pharyngitis), radiological evidence of septic thrombophlebitis of the internal jugular vein, and the detection of anaerobic pathogens, generally Fusobacterium necrophorum [1]. Lemierre's syndrome is a rare disorder, with an incidence rate ranging from 0.6 to 2.3 cases per million people. An even rarer form of this condition is the otogenic Lemierre's syndrome, which can manifest after acute otitis media, mastoiditis, or sporadically after an acutely infected cholesteatoma in children. In adults, however, otogenic Lemierre's syndrome is less well documented. The onset of otogenic Lemierre's syndrome is associated with septic pulmonary microemboli, in a way similar to Lemierre's syndrome, which is characterized by pulmonary metastatic infections in about 85% of patients [3].

Uncommon bacteriology in Lemierre's syndrome may contribute to diagnostic delays. Healy et al. described a case of bacteremia involving Enterococcus and Escherichia coli, which delayed the diagnosis of Lemierre's syndrome because blood cultures commonly reveal Fusobacterium necrophroum [4]. Other pathogens that may be responsible for otogenic Lemierre's syndrome include Bacteroides and Proteus species. In addition, Fusobacterium necrophroum usually takes six to eight days to incubate; this may also contribute to a delay in diagnosing Lemierre's syndrome. In our patient, after starting an empiric course of antibiotic treatment for severe bilateral pneumonia and septic shock, the blood cultures for Enterococcus raffinosus and Proteus mirabilis were positive, as were the intraoperative tissue cultures for Enterococcus raffinosus, Proteus mirabilis, and Pseudomonas aeruginosa. Since these bacteria are uncommonly associated with Lemierre's syndrome, it was not possible to make a diagnosis of Lemierre's syndrome. Therefore, we searched for alternative causes of bacteremia (e.g., respiratory and gastroenterological origins), resulting in a delay in diagnosis [5].

In retrospect, our patient had a jugular vein thrombosis discovered during central catheterization. This finding should have prompted further investigation for evidence of a septic focus in the head and neck. The infection was likely to have developed prior to the insertion of the central catheter and may have been an active ongoing condition in the head and neck. In the present case, it is believed that the infected cholesteatoma coalesced into a peri-sinus abscess, leading to sigmoid sinus thrombosis that then spread into the internal jugular vein [6]. Delay in the definitive management of the infected ear may result in local complications such as profound sensorineural hearing loss and intracranial infection, as well as life-threatening septic shock or mortality [2,7].

Depending on the severity of the condition, treatment of otogenic Lemierre’s syndrome may include aggressive surgical eradication and culture-directed intravenous antibiotic therapy. The infected cholesteatoma in our patient caused local septic thrombosis and bacteremia, both of which were unlikely to be resolved by conventional antibiotic therapy alone. As a result, mastoidectomy was indicated to clear the infection source within the middle ear and peri-sigmoid area. There has been considerable variation in the degree of surgical treatment based on intraoperative findings among various authors. Desphegel et al. reported two cases of middle ear granulation tissue and osteitis treated simply by cortical mastoidectomy and the insertion of a ventilation tube [8], whereas Stokroos et al. reported a case requiring repeat exploratory mastoidectomy and internal jugular vein ligation after initial mastoidectomy due to sigmoid sinus thrombosis [9]. The key principles of treatment are to ensure adequate middle ear ventilation, control infection sources, and perform an early surgical intervention.

The role of anticoagulation therapy in Lemierre's syndrome is primarily to minimize the spread of the septic thrombosis that has formed within the internal jugular vein into the intracranial space. In a systematic review conducted by Schulman et al., it was concluded that anticoagulation was associated with lower risks of both venous thromboembolism and septic thrombi, while bleeding risk did not significantly differ from that of untreated patients [10]. As in our patient, anticoagulation combined with surgical clearance of infection facilitated resolution of the septic thrombus within the internal jugular vein thrombus. There were no bleeding complications perioperatively, further validating anticoagulation's role in the treatment of Lemierre's syndrome.

Lemierre's syndrome is a highly treatable disease in modern times, with antibiotics playing a key role in dramatically reducing mortality rates from 90% in the pre-antibiotic era to 4–18% today [11]. In cases of otogenic Lemierre's syndrome, the optimal treatment may include a combination of antibiotic therapy and surgical intervention, as was the case here. Even though more than half of Lemierre's syndrome patients require admission to intensive care units, accurate early diagnosis is crucial for implementing appropriate supportive treatment and reducing long-term morbidity and mortality. In light of this, physicians should be aware of Lemierre's syndrome as a rare but potentially life-threatening condition, which is eminently treatable.

If a patient is unable to provide detailed information about their past due to respiratory failure requiring intubation, or if a language barrier is present, an investigative history through other methods and a complete physical examination must still be performed, as the delay in diagnosis may have severe consequences. By conducting a thorough physical examination and history taking, a clinician can better guide the clinical pursuit of septic foci and avoid the need to rely on overburdened imaging or antimicrobial resources within a public healthcare system.

In patients with severe bilateral pneumonia, atypical organisms to be identified in their blood cultures, and who do not respond to empirical antibiotic therapy, a high index of suspicion for Lemierre's syndrome is required. Additionally, internal jugular vein thrombosis may indicate otogenic Lemierre's syndrome, and further investigation should be conducted to identify potential septic foci in the head and neck region.

Received date: January 25, 2022

Accepted date: February 10, 2022

Published date: March 02, 2022

Writing, content analysis, and formatting of manuscripts by Pei Yuan Fong; writing and content analysis of manuscripts by Yew Meng Chan and Joyce Zhi’en Tang.

The study is in accordance with the ethical standards of the 1964 Helsinki declaration and its later amendments or comparable ethical standards. According to the Centralized Institutional Review Board (CIRB) Guidelines for SingHealth, this case report was exempt from research approval.

A consent was obtained from the patient prior to the use of de-identified patient data for academic and educational purposes, including publication in a journal.

Data sharing does not apply to this article since no datasets were generated or analysed during the current study.

This research has received no specific grant from any funding agency either in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

There are no conflicts of interest declared by either the authors or the contributors of this article, which is their intellectual property.

It should be noted that the opinions and statements expressed in this article are those of the respective author(s) and are not to be regarded as factual statements. These opinions and statements may not represent the views of their affiliated organizations, the publishing house, the editors, or any other reviewers since these are the sole opinion and statement of the author(s). The publisher does not guarantee or endorse any of the statements that are made by the manufacturer of any product discussed in this article, or any statements that are made by the author(s) in relation to the mentioned product.

© 2022 The Author(s). This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (CC-BY). In accordance with accepted academic practice, anyone may use, distribute, or reproduce this material, so long as the original author(s), the copyright holder(s), and the original publication of this journal are credited, and this publication is cited as the original. To the extent permitted by these terms and conditions of license, this material may not be compiled, distributed, or reproduced in any manner that is inconsistent with those terms and conditions.

The present study demonstrated that TEES could be a satisfying alternative to traditional microscopic surgery for the management of congenital cholesteatoma, even in pediatric patients. However, one-handed surgery demands greater skill and requires more practice to achieve a good outcome.

Authors reported a case of cholesteatoma that mimicked facial neurinoma. To avoid confusion in such cases, diffusion-weighted MRI may be useful in preoper-ative differential diagnosis.

Newly discovered epidemiological evidence linking cholesteatoma to depression suggests that routine screening and monitoring of psychological status among cholesteatoma patients is warranted. Policies aimed at the early detection and timely treatment of comorbid depression following diagnosis with cholesteatoma could enhance health promotion and disease prevention.

The author reports a case involving a 59-year-old man with delayed presentation of a huge mastoid cholesteatoma complicated by skull base erosion and cerebrospinal fluid leakage. Delayed presentation of this disease entity can have negative health consequences for patients. Regular otologic examinations, audiologic follow-up, and imaging examinations are viewed as the most effective strategies for the prevention of this type of situation. Early recognition of cholesteatomas is essential, as appropriate and timely treatment can prevent this rare comorbid condition from becoming fatal.

The authors describe a 41-year-old man who suffered retraction-related complications that may have been missed or delayed. The present case illustrates the potential dangers associated with tympanic retraction pockets, despite the fact that their bottoms are clear and clean. The article discusses the reasons for the lack of consensus among otologists regarding the appropriate way to treat tympanic membrane retractions. There is further discussion regarding the challenges associated with early surgical intervention.

This study investigates the efficacy of conservative management using 5-fluorouracil (5-FU) for treating cholesteatoma in ambulatory care settings, offering an alternative for patients who prefer to avoid surgery. Over 13 years, 15 ears of 14 patients were treated with a 5% 5-FU cream and assessed using Takahashi's efficacy criteria. The results revealed positive outcomes, with 87% of cases deemed good and 13% as fair, with no poor evaluations. This approach may be suitable for specific populations, such as older adults and individuals in remote areas with limited access to specialized healthcare services.

Esophageal granular cell tumors (GCT) represent a rare entity of tumors of the esophagus. Patients with esophageal GCTs are usually asymptomatic, with the lesion most commonly presenting as an incidental finding on endoscopy. The GCTs of the esophagus are poorly understood in medical literature. It is unknown if they undergo malignant degeneration, whether the malignancy can be diagnosed preoperatively, and how the tumor can be managed. The authors evaluated the clinical and pathologic features of all esophageal GCTs at their institution to understand them better.

Fong PY, Chan YM, Tang JZ. Otogenic Lemierre’s syndrome with bilateral metastatic pneumonia: Report of an unusual case in a male. Arch Otorhinolaryngol Head Neck Surg 2021;6(1):5. https://doi.org/10.24983/scitemed.aohns.2022.00158