Branchial cleft cysts are congenital anomalies that arise from the incomplete involution of branchial cleft structures, most commonly occurring in the lateral neck along the anterior border of the sternocleidomastoid muscle. In this report, we describe a case featuring a branchial cleft cyst that presents in an atypical location, specifically the midline area inferior to the hyoid bone. A 77-year-old male presented with a five-year history of an enlarging cystic mass located on the left anterior aspect of the cervical region. A review of the imaging findings strongly suggested an infrahyoid thyroglossal duct cyst. However, following the surgical excision of the cystic mass, postoperative histopathological evaluation confirmed the diagnosis of a branchial cleft cyst. Although exceedingly rare, branchial cleft cysts should be considered in the differential diagnosis of midline neck masses in adults. Atypical presentations of branchial cleft cysts highlight the diagnostic challenges posed by midline cystic neck masses and underscore the importance of histopathological confirmation. By comprehensively reviewing similar reported cases, this article enriches our understanding of the etiological theories behind these anomalies. It also underscores the critical role of histopathological evaluation and revisits the debate regarding the utility of fine needle aspiration biopsy in the context of diagnosing midline neck masses.

Branchial cleft cysts typically manifest as asymptomatic, non-tender soft tissue masses, originating from the incomplete involution of branchial cleft structures. These cysts are predominantly located in the lateral aspect of the neck, along the anterior border of the sternocleidomastoid muscle (SCM). Management typically involves surgical removal. This approach aims to mitigate potential complications, including enlargement, infection, inflammation, airway obstruction, and the risk of malignancy [1,2].

While predominantly observed in the lateral neck, instances of branchial cleft cysts in atypical sites, including the nasopharynx, thyroid gland, and mediastinum, have been documented [3–5]. This report details a rare case of a midline branchial cleft cyst, which was initially misdiagnosed as an infrahyoid thyroglossal duct cyst based on imaging findings. Through this case, we seek to underscore the importance of including branchial cleft cysts in the differential diagnosis of midline neck masses, despite their rarity.

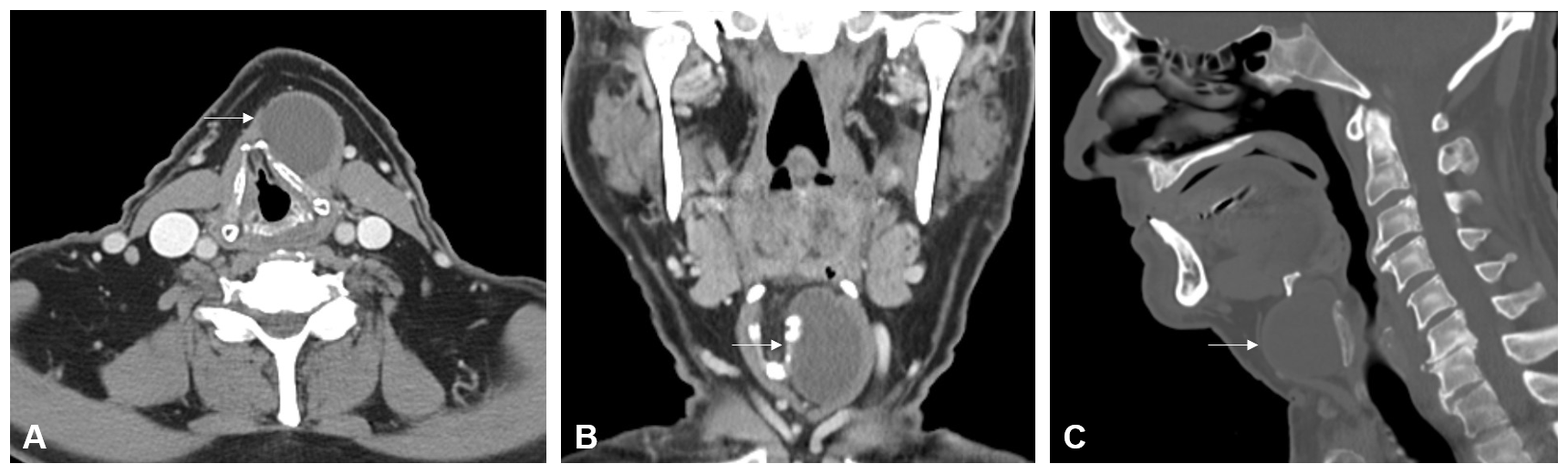

A 77-year-old male patient presented with a five-year history of an enlarging cystic mass in the left anterior cervical region. He reported occasional throat clearing and dysphagia, affecting both solids and liquids, but denied experiencing tenderness or signs of inflammation. Physical examination revealed a 4-cm mobile, non-tender mass palpable to the left of the midline. Further assessment through flexible nasolaryngoscopy showed no remarkable findings, with evidence of right nasal cavity patency, absence of lesions or masses at the base of the tongue and vallecula, mobility of the true vocal cords without lesions, and effective laryngeal swallow function. Computed tomography (CT) of the neck identified a circumscribed, hypodense, cystic-like mass, measuring 3.6 x 3.0 x 4.1 cm, located in the left paramedian cervical region, anterior to the left ala of the thyroid cartilage, and situated deep to the left thyrohyoid strap musculature. This mass caused moderate displacement of the thyroid cartilage toward the right side (Figure 1). The patient's social history is notable for intermittent tobacco use, consumption of two beers per day, and a denial of recreational drug use.

Figure 1. Contrast-enhanced computed tomography imaging shows a circumscribed hypodense cystic-like mass (white arrow) located just below the hyoid bone on (A) axial, (B) coronal, and (C) sagittal planes. The mass is located anterior to the left ala of thyroid cartilage and deep to the left thyrohyoid strap musculature in the left paramedian cervical region.

Based on the clinical examination and imaging findings, an infrahyoid thyroglossal duct cyst was suspected, and an excisional biopsy was performed under general anesthesia. An incision was made in the cervical crease at the equator of the mass. The strap muscles were separated along the midline, and the overlying strap muscles were elevated. Fibrous material was encountered, which presented difficulties during dissection due to its adherence to the thyroid cartilage. During the dissection directed superiorly, the cyst was inadvertently entered, resulting in the spillage of purulent material. Decompression of the cystic mass allowed for visualization of a tract extending laterally beyond the left lesser cornu of the hyoid bone into the left neck. The patient tolerated the procedure well and without any complications.

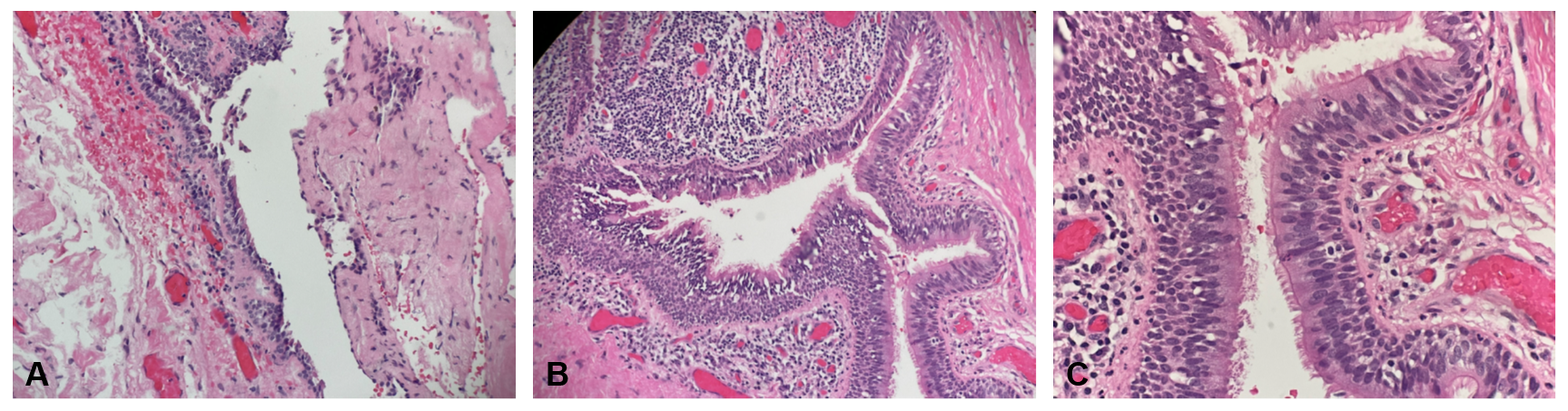

Postoperative gross pathological examination revealed a tan, collapsed cyst measuring 4.3 x 2.2 x 1.5 cm, with a cyst wall thickness of 0.2 cm. Serial sectioning uncovered a unilocular cyst filled with golden-yellow, pasty material. Histopathological analysis of the excised left infrahyoid mass displayed a focally excoriated cyst lining composed of stratified, ciliated columnar epithelium, accompanied by a focally nodular lymphocytic infiltrate. These findings confirmed the diagnosis of a branchial cleft cyst (Figure 2).

Figure 2. (A) A low-magnification view (hematoxylin-eosin stain, 40x) reveals the cystic space. (B) At medium magnification (hematoxylin-eosin stain, 100x) and (C) at high magnification (hematoxylin-eosin stain, 200x), the images display a focally excoriated cyst lining composed of stratified, ciliated columnar epithelium. The cyst wall exhibits focally nodular lymphocytic infiltration. These histological features are consistent with those of a branchial cleft cyst.

Branchial cleft cysts are congenital anomalies arising from the incomplete obliteration of the first through fourth pharyngeal clefts during embryogenesis [1]. Among these, second branchial cleft cysts are the most prevalent, typically located anteromedial to the SCM and accounting for approximately 95% of all branchial cleft anomalies [2]. First and third branchial cleft cysts, although less frequent, constitute about 7% and 8% of these anomalies, respectively [2]. Fourth cleft cysts are exceptionally rare, representing only 1% of the anomalies, and are most often found at the left lower border of the SCM [2]. While these anomalies usually manifest in childhood, branchial cleft cysts can occasionally present in adulthood, marking a delayed onset [1].

Literature Review of Cases (Table 1)

The etiology of branchial cleft cysts is a subject of considerable debate, with four primary theories proposed: persistence of the pre-cervical sinus, incomplete obliteration of branchial mucosa, cystic degeneration of cervical lymph nodes, and incomplete obliteration of the thymopharyngeal duct [6]. The occurrence of branchial cleft cysts at the midline of the neck, however, presents an unusual scenario that challenges these established theories on the embryological development of branchial anomalies.

To our knowledge, only three instances of midline branchial cleft cysts have been documented. Our comparative analysis, which includes the present case, underscores variations in demographics, symptoms, and characteristics of the masses across various global regions — specifically, India, Korea, and the United States (Table 1). These cases span a broad age range from 3 to 77 years and exhibit differences in the locations, sizes, and imaging findings of the masses. Aggarwal et al. reported a branchial cleft cyst located in the midline, beneath the hyoid bone [7]. Narayana et al. described a branchial cleft case in the submental region [8], while Baek et al. identified a midline branchial cleft mass situated superficially to the sternohyoid [9]. Notably, fine needle aspiration (FNA) was employed in only one of these cases, rather than for all, and revealed a small lymphocyte count [9].

While all cases underwent excisional biopsy, intraoperative findings varied, with many indicating that the masses adhered to nearby structures. This variation in adherence patterns underscores the complex nature of midline branchial cleft cysts and their interactions with surrounding anatomical features. For example, Aggarwal et al. noted adherence to the strap musculature and pre-tracheal fascia [7], while Baek et al. observed attachment to the right sternohyoid muscle [9]. Our findings included mass adherence to the thyroid cartilage and a lateral tract extending beyond the left lesser cornu of the hyoid bone. Histopathologic analysis in three instances revealed cystic walls lined with stratified squamous and ciliated columnar epithelium, consistent with branchial cleft cysts [8,9]. The absence of complications post-excision in all cases speaks to the effectiveness of this management approach.

This comparative analysis of four cases illuminates the exceedingly rare presentation of midline branchial cleft cysts and underscores their significance in the differential diagnosis of neck masses.

Challenges in Differential Diagnosis

Differential diagnoses for midline neck masses include dermoid cysts and thyroglossal duct cysts. Both can mimic branchial cleft cysts on CT imaging, manifesting as well-defined, hypodense, and unilocular masses [2]. Owing to these similar imaging characteristics, Narayana et al. provisionally diagnosed a case as a dermoid cyst [8]. In our study, the anatomical relationship of the cyst-like mass to the hyoid bone informed our initial diagnosis of a thyroglossal duct cyst. Nevertheless, the identification of a laterally directed tract extending beyond the lesser cornu of the hyoid bone during surgical excision challenged the certainty of the initial preoperative diagnosis. This suspicion was later validated by postoperative histopathological findings. Upon histopathological comparison, thyroglossal duct cysts are distinguished by nonkeratinizing stratified epithelium, in contrast to branchial cleft cysts, which are demarcated by a lining of stratified squamous, pseudostratified, or ciliated columnar epithelium [6].

Another critical diagnosis to consider is squamous cell carcinoma of the head and neck (HNSCC), which typically presents as firm masses and frequently metastasizes to nearby deep cervical lymph nodes. Masses, particularly those with cervical metastases from human papillomavirus (HPV)-positive HNSCC, may be incorrectly identified as branchial cleft cysts at levels II, III, and IV, owing to their common lateral neck location [10–13]. Such misdiagnoses can substantially affect patient care, resulting in delayed treatment for urgent cases and reduced survival rates.

The difficulty in differentiating malignant cystic neck lesions from benign branchial cleft cysts primarily stems from their similar radiographic profiles and the limited diagnostic yield of FNA biopsy [10,11]. Consequently, age becomes a crucial factor in the clinical evaluation for differential diagnosis of neck masses, with patients older than 40 years showing an increased likelihood of metastatic cervical lymph nodes [10]. According to the current literature, the prevalence of carcinoma in cervical cysts, initially identified as branchial cleft cysts, varies between 4% and 24%, but this figure escalates to 80% among those aged over 40 years [14–16].

Therefore, a comprehensive preoperative evaluation is essential in patients over 40 years presenting with neck masses, due to the elevated risk of malignancy. The advanced age of our patient (77 years), along with risk factors such as alcohol and tobacco use, and the presentation of a nontender, enlarging neck mass with persistent throat clearing and dysphagia, necessitated a thorough clinical assessment for malignancy. However, the initial presentation consistent with a thyroglossal duct cyst, characterized by its midline location, physical examination findings, and imaging, reduced our suspicion of cancerous etiologies.

Our case underscores the significance of including branchial cleft cysts in the differential diagnosis of midline neck masses. It also highlights the need to assess the efficacy of different diagnostic approaches for cystic neck lesions, while concurrently conducting comprehensive clinical evaluations for malignancy, especially among patient cohorts with heightened susceptibility to malignancies.

FNA: Role and Controversy

Standard diagnostic procedures for midline neck masses commonly entail performing FNA biopsies ahead of surgical interventions. It is noteworthy that among the four cases reported (Table 1), FNA was conducted prior to tumor removal in only one instance. In our patient's case, the initial presentation strongly indicated a thyroglossal duct cyst, evidenced by its manifestation as a midline neck mass and its anatomical proximity to the hyoid bone, as shown on radiographic imaging. Therefore, FNA was not undertaken, with the decision made to proceed directly to an excisional biopsy to obtain a definitive diagnosis.

However, the potential for misclassifying cystic metastases as branchial cleft cysts may lead to delays in diagnosis and treatment of critical cases. Such misclassification can precipitate early open biopsy of metastatic cancers, reduce survival rates, exacerbate local wound necrosis, and increase the likelihood of cancer recurrence [10]. Therefore, there is support for utilizing FNA biopsy as a minimally invasive method that offers cytological insights, assisting in differential diagnosis and preoperative evaluation.

FNA biopsy is highly valued for its effectiveness in evaluating neck lesions suspected of malignancy, especially in cases of cystic lateral neck masses and solid neck tumors. A noteworthy study by Sira et al. revealed that, among 47 cases of metastatic cancer, 3 lesions (6.4%) were initially misidentified as branchial cysts but were later correctly diagnosed as squamous cell carcinomas [14]. Consequently, a comprehensive diagnostic approach is advised for adults presenting with lateral cervical cystic masses. This approach should commence with a radiological assessment utilizing CT or magnetic resonance imaging (MRI), followed by FNA cytology to gather preliminary cytological information, and culminate in an excisional biopsy to establish a definitive diagnosis. Intraoperative frozen section analysis may additionally assist in guiding surgical decision-making [14].

To enhance the diagnostic accuracy of FNA cytology for distinguishing between branchial cleft cysts and HNSCC, Layfield et al. conducted an analysis of 19 cytologic features across 33 histologically verified cystic lesions, which included 21 instances of HNSCC and 12 branchial cleft cysts [17]. Their multivariate analysis pinpointed the most significant cytologic indicators as a high nuclear-cytoplasmic ratio, irregular nuclear membranes, and the presence of small cell clusters.

Nevertheless, the necessity of employing FNA biopsy to identify a primary tumor before proceeding with the excision of a midline neck cyst continues to provoke debate. The challenge of accurately detecting cancer within a midline neck cyst arises from the often-limited efficacy of radiological techniques and the variable reliability of FNA biopsy [10,18]. Research indicates that FNA sensitivities range from 30% to 50%, with the rate of false negatives in diagnosing cystic neck metastases reported between 50% and 67% [11,12]. The challenges of using FNA biopsy as a reliable diagnostic method for cystic metastases often stem from the low cell density in the aspirate and the simultaneous presence of inflammatory cells, dystrophic epithelial cells, and cellular debris [11,12]. Therefore, excisional biopsy remains essential for securing a definitive diagnosis. All four reported cases of midline branchial cleft cysts (Table 1) underwent excisional biopsy, which histopathological analysis subsequently confirmed. When considering the application of FNA biopsy prior to surgical removal of a tumor, critics have voiced concerns regarding its cost-effectiveness and the potential risk of exposing patients to unnecessary interventions, particularly since many cystic lesions are typically benign branchial cleft cysts.

Complications of Untreated Branchial Cleft Cysts

Complications arising from untreated branchial cleft cysts encompass recurrent infections and abscess formations, leading to scarring and the potential compromise of adjacent structures. A rare but significant complication is the transformation of branchial cleft cysts into branchial cleft cyst carcinoma (BCCC). BCCC originates from the malignant transformation of the stratified squamous epithelium into carcinoma within the lining of the cyst wall, with an incidence reported between 4% and 24% [19]. Characteristic features of BCCC may include imaging heterogeneity, extension beyond the lymph node capsule, and asymmetric thickening of the cystic outer wall [10]. Consequently, surgical intervention is recommended upon suspicion of a branchial cleft cyst, given the heightened risks of infection, abscess development, and malignancy. Surgical removal of branchial cleft cysts is typically curative, exhibiting a low recurrence rate [7]. In all four documented cases of branchial cleft cysts, surgical excision was executed without complications, demonstrating effective management for these uncommon cyst presentations.

Branchial cleft cysts represent congenital anomalies due to incomplete involution of branchial apparatus structures. This case highlights an uncommon anatomical manifestation of a branchial cleft cyst, underscoring the diverse clinical presentations of branchial cleft anomalies. Despite their rarity, branchial cleft cysts should be contemplated in the differential diagnosis of midline neck masses in adults. Analyzing the limited reported cases offers crucial insights into diagnostic approaches and management tactics, aiming to enhance clinical decision-making for unusual presentations of branchial cleft cysts.

Received date: December 30, 2023

Accepted date: February 05, 2024

Published date: March 05, 2024

The authors extend their gratitude to the Departments of Otolaryngology-Head & Neck Surgery and Pathology at the Bay Pines Veterans Affairs Healthcare System for their support of this research endeavor.

The manuscript has not been presented or discussed at any scientific meetings, conferences, or seminars related to the topic of the research.

The study adheres to the ethical principles outlined in the 1964 Helsinki Declaration and its subsequent revisions, or other equivalent ethical standards that may be applicable. These ethical standards govern the use of human subjects in research and ensure that the study is conducted in an ethical and responsible manner. The researchers have taken extensive care to ensure that the study complies with all ethical standards and guidelines to protect the well-being and privacy of the participants.

The author(s) of this research wish to declare that the study was conducted without the support of any specific grant from any funding agency in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors. The author(s) conducted the study solely with their own resources, without any external financial assistance. The lack of financial support from external sources does not in any way impact the integrity or quality of the research presented in this article. The author(s) have ensured that the study was conducted according to the highest ethical and scientific standards.

In accordance with the ethical standards set forth by the SciTeMed publishing group for the publication of high-quality scientific research, the author(s) of this article declare that there are no financial or other conflicts of interest that could potentially impact the integrity of the research presented. Additionally, the author(s) affirm that this work is solely the intellectual property of the author(s), and no other individuals or entities have substantially contributed to its content or findings.

It is imperative to acknowledge that the opinions and statements articulated in this article are the exclusive responsibility of the author(s), and do not necessarily reflect the views or opinions of their affiliated institutions, the publishing house, editors, or other reviewers. Furthermore, the publisher does not endorse or guarantee the accuracy of any statements made by the manufacturer(s) or author(s). These disclaimers emphasize the importance of respecting the author(s)' autonomy and the ability to express their own opinions regarding the subject matter, as well as those readers should exercise their own discretion in understanding the information provided. The position of the author(s) as well as their level of expertise in the subject area must be discerned, while also exercising critical thinking skills to arrive at an independent conclusion. As such, it is essential to approach the information in this article with an open mind and a discerning outlook.

© 2024 The Author(s). The article presented here is openly accessible under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (CC-BY). This license grants the right for the material to be used, distributed, and reproduced in any way by anyone, provided that the original author(s), copyright holder(s), and the journal of publication are properly credited and cited as the source of the material. We follow accepted academic practices to ensure that proper credit is given to the original author(s) and the copyright holder(s), and that the original publication in this journal is cited accurately. Any use, distribution, or reproduction of the material must be consistent with the terms and conditions of the CC-BY license, and must not be compiled, distributed, or reproduced in a manner that is inconsistent with these terms and conditions. We encourage the use and dissemination of this material in a manner that respects and acknowledges the intellectual property rights of the original author(s) and copyright holder(s), and the importance of proper citation and attribution in academic publishing.

The article discusses a complex case of a 51-year-old Chinese woman diagnosed with a pituitary neuroendocrine tumor in the clivus, characterized by its invasive nature and atypical symptoms, leading to diagnostic challenges between chordoma and chondrosarcoma. Achieving a correct diagnosis through a transsphenoidal biopsy enabled effective surgical removal of the tumor without complications. Highlighting the critical role of biopsy for accurate diagnosis, especially with atypical imaging, the study showcases the efficacy of minimally invasive transnasal endoscopic biopsy techniques. It emphasizes the importance of a multidisciplinary approach for optimal patient outcomes in complex pituitary tumors, underlining the need for vigilance and adaptability in managing such rare conditions. This contributes valuable insights to the medical field, particularly for neurosurgery, otorhinolaryngology, and endocrinology practitioners.

A significant increase in peripheral nerve surgery has occurred in recent years due to improvements in surgical techniques. In most reconstructive procedures, sensory restoration is frequently neglected in preference to restoring motor function. Along with increasing the risk of developing injuries to the body, patients who lose protective sensations are more likely to develop neuropathic pain and depression, which adversely affect their quality of life. As regaining sensory function is important, the study examines a variety of techniques that may be useful for restoring sensory function across various body parts.

This study introduces an advanced tubularized radial artery forearm flap (RAFF) technique, marking an enhancement over traditional methods in addressing complex nasal reconstructions. It integrates functional and aesthetic considerations through a structured, multi-stage reconstruction process, emphasizing the use of tubularized flaps. Key learning points include the detailed crafting of stable nasal passages, strategic use of costal cartilage for robust structural support, and tailored postoperative care with silicone splints. The tubularized RAFF technique not only optimizes patient outcomes and quality of life but also provides plastic surgeons with critical insights to refine their techniques in facial reconstruction. Indispensable for professionals in the field, this article enriches the understanding of sophisticated reconstructive challenges and solutions.

This article presents a crucial case report on potential wound healing complications linked to fremanezumab, a calcitonin gene-related peptide-targeting antibody for migraine prevention. It documents the first known instance of delayed wound healing following a free flap breast reconstruction, underscoring the need for heightened clinical vigilance and individualized patient assessment in perioperative settings. Highlighting significant safety data gaps, the report advocates for comprehensive research and rigorous post-marketing surveillance. The findings emphasize the importance of balancing the risks of delayed wound healing with the need for effective disease control, especially when using biologic agents for chronic conditions. This article is essential for medical professionals managing patients on biologic therapies, offering critical insights and advocating for a personalized approach to optimize patient outcomes. By presenting novel observations and calling for further investigation, it serves as a vital resource for enhancing patient care and safety standards in the context of biologic treatments and surgical interventions.

The PLOSEA technique detailed in this study addresses the significant challenge of managing large vessel size discrepancies in microvascular surgery with an innovative and accessible method. By partially obliterating the larger vessel lumen before anastomosis, the technique reduces risks of thrombosis and misalignment, simplifying the procedure without sacrificing effectiveness. This advancement is particularly valuable as it allows surgeons with varying levels of experience to perform complex reconstructions with greater confidence and improved patient outcomes. A key feature is the inclusion of a detailed video demonstration, providing a dynamic and comprehensive visual guide that surpasses traditional static images. This video meticulously elucidates each procedural step, enhancing understanding and facilitating the practical application of the technique. Emphasizing technical precision, patient safety, and surgical efficiency, this study offers a compelling narrative for medical professionals. The transformative impact of the PLOSEA technique on surgical practice underscores its importance, presenting a novel approach that can enhance the quality of care and expand the capabilities of microsurgeons worldwide.

This manuscript showcases an advanced surgical approach for treating malignant giant cell tumor of bone, emphasizing precision and ethical considerations. It leverages innovative pedicled flap technologies, as opposed to free flaps, enhancing limb functionality and patient quality of life. This technique equips surgeons with evidence that tailored surgical strategies can significantly improve outcomes in complex cases. The paper discusses technical challenges and highlights the application of supercharging and superdrainage techniques in limb reconstructions, methods well-established in microsurgery but infrequently used in oncological contexts. These techniques are crucial for optimizing flap viability and ensuring surgical success. Additionally, the manuscript underscores the profound impact of these advancements on patient lives, offering hope and showcasing tangible benefits. This narrative, blending scientific analysis with patient stories, enriches the understanding of limb reconstruction innovations in oncological surgery, making it invaluable for surgeons.

This article presents the first comprehensive review of refractory chylous ascites associated with systemic lupus erythematosus, analyzing 19 cases to propose an evidence-based therapeutic framework. It introduces lymphatic bypass surgery as an effective option for this rare complication, overcoming the limitations of conventional treatment. By integrating mechanical drainage, immunomodulation, and lymphangiogenesis, this approach achieves rapid and sustained resolution of ascites. The findings offer a novel surgical strategy for autoimmune lymphatic disorders and prompt a re-evaluation of their complex pathophysiology. This study demonstrates how surgical innovation can succeed where traditional therapies fail, offering new hope in managing refractory autoimmune disease.

Motorcycle chain-induced fingertip amputations represent a reconstructive dead end, where severe crushing and contamination traditionally compel revision amputation. The authors dismantle this exclusion criterion, reporting an 83% salvage rate using a modified protocol of radical debridement, strategic skeletal shortening, and simplified single-vessel supermicrosurgery. By eschewing complex grafting for tension-free primary anastomosis, the authors successfully restored perfusion in ostensibly

This article is noteworthy for its exploration of a rare case involving a midline branchial cleft cyst in a 77-year-old male, presenting as a left anterior cervical cystic mass. Initially, it was suspected to be an infrahyoid thyroglossal duct cyst based on imaging, but the diagnosis was revised after surgical excision through histopathological analysis. This case, along with the mention of only three other similar cases in the literature, significantly enriches the understanding of branchial cleft cysts, particularly their atypical presentations and the importance of considering them in the differential diagnosis of midline neck masses in adults. The article's scholarly merit and unique case study make it a worthy candidate for publication. However, this article may require revisions due to identifiable issues such as a constrained comparative analysis and an inadequate review of existing literature, as indicated below.

The article presents a unique case of a branchial cleft cyst, initially misidentified as an infrahyoid thyroglossal duct cyst, attributed to its rare midline location. This case underscores the vital importance for healthcare professionals to include branchial cleft cysts in the differential diagnosis of midline neck masses. While the report is informative and adds significant value to the medical literature, it requires further enhancement in terms of detailed information, contextual depth, and improved presentation to meet the high standards of a reputable medical journal. To be considered suitable for publication, the article needs to address these specific issues and enrich its content to ensure a rigorous presentation.

The article highlights an extraordinary medical case—a branchial cleft cyst located in an unexpected midline position. Typically found along the anterior border of the sternocleidomastoid muscle in the lateral neck, this rare occurrence challenges conventional diagnostic expectations. Initially misidentified as an infrahyoid thyroglossal duct cyst based on imaging, the definitive diagnosis emerged only through postoperative histopathological analysis. This case significantly contributes to our understanding of branchial cleft cysts and their unusual presentations in adults, given that there are only three similar cases documented in the literature. In summary, this article is a must-read for medical professionals as it not only enriches their understanding of branchial cleft cysts, particularly in their atypical presentations, but also reinforces the principles of thorough evaluation and differential diagnosis in clinical practice through its review of literature. Considering the article's distinctiveness and substantial academic merit, I contend that it merits publication in its current form, subject to the implementation of some minor revisions.

Sia MJ, Kapadia IH, Hahn JS. Midline branchial cleft cyst initially misdiagnosed as a thyroglossal duct cyst: A rare case study and literature review. Arch Otorhinolaryngol Head Neck Surg 2024;8(1):2. https://doi.org/10.24983/scitemed.aohns.2024.00181