Artificial intelligence (AI) is evolving from an auxiliary tool into a foundational component of clinical decision making and medical knowledge synthesis. Despite this progress, a persistent mismatch remains between research priorities and unmet clinical needs. In otolaryngology, approximately 55% of AI studies focus on diagnosis, whereas only 5% address prognosis, limiting the ability of AI systems to inform future clinical trajectories and long-term outcomes that are most relevant to patients. Although AI systems demonstrate increasing fluency, their integration into clinical workflows introduces distinct risks to diagnostic and causal reasoning. Using otolaryngology as a representative model, a specialty reliant on multimodal data including audiometric, endoscopic, and acoustic inputs, this article illustrates how fluent outputs may obscure underlying reasoning fallacies. These risks are particularly salient in high-risk settings, such as delayed recognition of laryngeal cancer or missed detection of cholesteatoma. As AI increasingly informs complex clinical judgments, the nature of risk shifts from isolated errors to systemic vulnerabilities in the medical evidence base. External validation frequently demonstrates performance attenuation, indicating limited generalizability. In parallel, data contamination, including data poisoning at levels as low as 0.001%, may increase the likelihood of erroneous clinical recommendations, while selective reporting of favorable internal results may foster unwarranted clinician confidence. Although prior work has extensively examined algorithm-level performance, explainability, and causal learning, it has not specified how clinicians should evaluate AI outputs in real-world, high-risk decision making. To address this gap, this article proposes a multidimensional reasoning defense framework composed of four components: premise verification, terminological precision, evidence appraisal, and causal analysis. By treating AI outputs as provisional, testable hypotheses and enabling flexible, risk-proportionate scrutiny within clinician-led causal reasoning, the framework operationalizes clinician oversight while preserving professional accountability and patient safety.

Artificial intelligence (AI) is fundamentally redefining the landscape of medical decision making and scientific knowledge curation [1–3]. This paradigm shift alters how clinicians synthesize and apply evidence at the point of care, as contemporary large language models now demonstrate sophisticated clinical reasoning by interpreting complex, multidimensional clinical scenarios [4,5].

However, the deployment of these models in high-stakes environments necessitates rigorous mechanisms to support factual accuracy. To address the inherent limitations of standalone models, retrieval-augmented generation (RAG) integrates real-time querying of peer-reviewed literature and electronic health records [6,7]. By grounding outputs in specific evidence, RAG establishes a verifiable framework with traceable evidence for medical recommendations. This architecture is specifically engineered to mitigate hallucinations, defined as the generation of factually incorrect yet linguistically plausible information, and to support the alignment of model outputs with established clinical guidelines [8–10]. Implementing these rigorous standards is not merely a technical safeguard but a clinical necessity, as it fosters clinician trust and patient safety essential for widespread adoption.

Beyond improving current clinical performance, the future integration of these systems may accelerate personalized medicine, optimize data interoperability, and enhance the management of rare diseases. In essence, AI transforms clinical practice from a reactive model to a proactive, data-driven paradigm. By identifying subtle patterns within massive datasets, these tools enable earlier risk detection and intervention, potentially improving longitudinal patient outcomes while reducing systemic health care costs [11].

Despite this transformative potential, the increasing fluency of AI-generated narratives poses a paradoxical risk: as outputs become more linguistically plausible, they may more effectively mask underlying hallucinations [8–10] and the insidious effects of data poisoning. The fundamental challenge remains how to preserve the integrity of clinical reasoning when the boundary between expert evidence and algorithmic fallacy becomes increasingly blurred.

This article employs otolaryngology, a field uniquely reliant on high-stakes multimodal data, as a representative model to illustrate the covert pathways through which AI may transition from superficial fluency to clinical fallacy. By analyzing representative applications across otology, rhinology, and laryngology, this article delineates the structural vulnerabilities of current systems and proposes a multidimensional reasoning defense framework. This structured approach, comprising premise verification, terminological precision, evidence appraisal, and causal analysis, empowers clinicians to transition from passive users of "black-box" tools to active guardians of the decisional process. Ultimately, a disciplined defense strategy is essential to reestablish physician leadership in medical judgment, ensuring that AI-assisted diagnosis remains grounded in the rigorous standards of medical evidence and patient safety.

The integration of AI within otolaryngology has evolved from a series of conceptual frameworks into sophisticated clinical decision-support systems that span the subspecialties of otology, rhinology, and laryngology. Current research primarily leverages machine learning methodologies, including deep learning and convolutional neural networks, to optimize diagnostic accuracy, image-based analysis, and intraoperative surgical navigation. Although these technological advances demonstrate substantial potential, the attainment of rigorous validation and effective clinical integration continues to be a primary challenge [12–15].

Evidence of Distribution Imbalance

A systematic narrative review involving 327 original deep-learning studies in otolaryngology identified a profound disparity in the distribution of AI applications [12]. Detection and diagnosis constituted the majority of the literature with 179 studies (55%), while image segmentation accounted for 93 studies (28%). By contrast, emerging applications represented 39 studies (12%), and prediction or prognostic assessments contributed only 16 studies (5%). This quantitative distribution indicates that research remains heavily anchored in diagnostic automation at the expense of longitudinal management strategies.

Prognostic Gap in AI Development

These data confirm that investigative efforts are currently prioritized toward recognition, diagnosis, and anatomical delineation. Consequently, prognostic assessment and risk stratification remain significantly underdeveloped as clinical domains. This discrepancy underscores a misalignment between academic research priorities and the practical requirements of clinical practice. While AI effectively identifies existing pathology, it offers insufficient guidance regarding the future clinical trajectory or long-term outcomes of patients. Bridging this prognostic gap is essential to transform AI from a diagnostic aid into a tool for actionable, long-term clinical guidance.

The clinical application of AI in otology is increasingly characterized by targeted advancements across specific diagnostic and therapeutic domains. These developments encompass representative areas such as vestibular assessment, objective audiologic testing, and automated imaging interpretation. Although these computational tools offer the potential for enhanced precision, their real-world utility remains contingent upon navigating inherent clinical constraints and anatomical complexities. Successfully integrating these technologies requires a rigorous evaluation of their diagnostic accuracy alongside their capacity to function within the nuances of human anatomy.

Hearing Assistive Technologies

In otology, the clinical implementation of AI has expanded from hearing assistive technologies to a broader range of applications, including balance disorders, objective audiologic testing, and middle ear imaging interpretation. In hearing aids, for example, the Siemens Centra device utilized machine learning as early as 2006 to adapt to individual preferences for volume and gain.

More recently, hearing technologies have been integrated with smartphones, leveraging enhanced sensing and on-device computing to detect speech, provide real-time translation, detect falls, and monitor general health status [15–18]. This progression from simple gain adjustments to comprehensive health monitoring illustrates the expanding role of AI in personalizing otologic care.

Integrated Platforms for Vestibular Disorders

AI applications in vertigo and balance disorders encompass both diagnostic classification and rehabilitation interventions. The EMBalance diagnostic platform classifies patients into diagnostic categories and provides a recommendation toolkit that assists primary care clinicians in requesting the key information required to reach a diagnosis. Because the system integrates multiple data-mining models, it can generate several plausible diagnoses for a given patient. Furthermore, whereas earlier systems were trained and tested using approximately 10 to 240 features, EMBalance utilizes approximately 350 features to characterize patient profiles [19].

From a rehabilitation perspective, virtual reality programs that combine interactive gaming with sensor-recorded performance have also been introduced. These approaches emphasize that vestibular rehabilitation systems should provide real-time visual, auditory, and tactile feedback to increase engagement and improve training effectiveness [20]. Such feedback loops are critical for facilitating neuroplasticity and the successful compensation of vestibular deficits.

Automated ABR Signal Classification

AI has also been applied to enhance the objectivity of auditory brainstem response (ABR) interpretation [13]. One study reported that a neural network model classified 190 ABR recordings into three categories (clear, inconclusive, and absent), achieving an accuracy of 92.9% and a sensitivity of 92.9% [21].

A separate study published in 2023 utilized deep learning to standardize and classify ABR images, reporting an accuracy of 84.9% [22]. These findings suggest that deep-learning algorithms can effectively mitigate the inter-observer variability often associated with manual ABR interpretation.

Automated Middle Ear Imaging

In imaging, convolutional neural network models show substantial potential for the automated recognition of tympanic membrane and middle ear infections. These models demonstrate a competitive accuracy of 95% for classifying tympanic membrane findings and middle ear effusion from otoscopic ear images [23]. The ability of convolutional neural networks to process visual data rapidly makes them ideal candidates for screening in primary care settings.

Clinical Constraints and Risks

In real-world practice, however, cerumen, debris, or granulation tissue within the external auditory canal frequently obscures the lesion site. If such confounding conditions are insufficiently represented in training data, AI systems may miss occult cholesteatoma at the initial presentation [24].

This concern is particularly salient in high-risk populations, such as children with cleft lip and palate, in whom the risk of cholesteatoma is reported to be 100 to 200 times higher than that in the general pediatric population [25]. Furthermore, more than 90% of these children develop otitis media with effusion before two years of age [25].

Consequently, the performance of AI models in these vulnerable groups may be significantly diminished without specialized training sets. Model development should therefore incorporate high-quality reference standards, such as image-guided video-telescopy with a reported diagnostic accuracy of 98% [25], to strengthen recognition robustness in anatomically complex cases.

The integration of AI into rhinology is increasingly defined by targeted advancements in diagnostic precision and surgical decision support. Recent investigations underscore the potential for computational models to refine the interpretation of clinical data and optimize perioperative outcomes within specific disease contexts. These technologies represent a shift toward more personalized, data-driven management of sinonasal pathology. By bridging the gap between qualitative observation and quantitative analysis, these computational advancements enable more objective clinical assessments. This section evaluates representative developments in these domains while acknowledging the rigorous validation required for broader clinical implementation.

Polyp Detection and Cytology Classification

In rhinology, AI methodologies have been primarily directed toward image interpretation and classification tasks. Machine-learning models have demonstrated substantial efficacy in automating high-volume diagnostic workflows. For nasal polyp detection, a convolutional neural network achieved an accuracy of 98.3%, a precision of 99%, and a recall of 98% when evaluated on a dataset of 2,560 images [26]. Similarly, in cytology classification, a model reported a diagnostic accuracy of 99% on testing data comprising 12,298 cells and 94% on validation data, with sensitivity exceeding 97% across datasets [27].

Automated Sinonasal CT Interpretation

To automate paranasal sinus evaluation, researchers utilized a pretrained Inception-v3 architecture, which was fine-tuned on paranasal sinus CT imaging to identify middle turbinate pneumatization. This approach achieved a diagnostic accuracy of 81% and an area under the curve of 0.93 [28]. These results suggest that established deep-learning architectures can be effectively repurposed for specialized radiologic tasks with high diagnostic fidelity. Such repurposed models offer a feasible pathway for developing specialized tools without the requirement for de novo architectural design.

Prognostic Modeling in Chronic Rhinosinusitis

Investigators developed an ensemble machine-learning model leveraging preoperative data from 242 patients undergoing endoscopic sinus surgery for chronic rhinosinusitis [29]. The model integrated patient-reported symptom inventories with 59 additional clinical variables to predict whether postoperative improvement would reach the minimal clinically important difference. Performance metrics included an accuracy of 87.8%, an area under the curve of 0.89, and a specificity of 93.3%.

By identifying patients unlikely to benefit from intervention, such models may refine surgical candidacy and improve resource allocation in outpatient settings. By shifting the investigative focus toward predictive outcomes, these models facilitate a more refined approach to surgical selection. However, the authors emphasized that multicenter validation remains a prerequisite for broader clinical deployment [29].

AI-Enhanced Intraoperative Surgical Navigation

Intraoperatively, AI may augment the precision of image-guided navigation systems. In endoscopic sinus surgery, one technique aligns intraoperative white-light endoscopic imagery with preoperative CT data, utilizing Structure from Motion (SfM) methods to infer three-dimensional sinonasal anatomy from surgical video [30]. This process effectively generates a dynamically updated intraoperative three-dimensional map. By providing real-time, high-resolution reconstructions, these systems enhance situational awareness regarding instrument position and adjacent critical anatomy. This enhanced visualization potentially reduces the risk of iatrogenic injury during complex maneuvers near vital structures.

CT-Based Radiomics and Disease Classification

Radiomics converts visually imperceptible CT features into computable descriptors that can be integrated with statistical or machine-learning models for disease classification and outcome prediction. A systematic review of CT-based radiomics studies in rhinology reported that diagnostic and prognostic performance commonly yielded an area under the curve between 0.73 and 0.92 [31], suggesting moderate to high discriminative ability. Standardization across institutional datasets remains the primary barrier to translating these radiomic insights into routine clinical workflows. Consequently, clinical translation remains contingent upon more standardized study designs and robust external validation across diverse patient populations.

The integration of AI in laryngology focuses on enhancing mucosal evaluation and the objective analysis of physiologic signals. These computational models facilitate the identification of upper airway pathology and the staging of respiratory disturbances. While these preliminary results underscore clinical utility, establishing these tools in routine practice requires rigorous validation across heterogeneous patient cohorts and clinical environments. By refining the interpretation of optical and acoustic data, these advancements may improve the objectivity of laryngeal assessments.

Automated Laryngeal Cancer Screening

AI development in laryngology has primarily targeted image-based diagnostics and the detection of abnormal voice patterns. A systematic review and meta-analysis of 15 studies encompassing 17,559 patients confirmed consistent performance in the AI-based detection of laryngeal cancer from laryngoscopic images, with a pooled sensitivity of 78% and a pooled specificity of 86% [32]. Such performance metrics indicate that AI-assisted imaging interpretation has approached the diagnostic threshold necessary for meaningful clinical decision support.

Vocal Fold Lesion Localization

Deep-learning models demonstrate the capacity to automatically localize vocal fold lesions on laryngoscopic images and distinguish benign from malignant pathology. Reported sensitivity ranges from 71% to 78% for malignant lesions and from 70% to 82% for benign lesions [33]. Importantly, the high inference speeds of these models now permit real-time interpretation during outpatient endoscopic procedures. This capability allows clinicians to identify suspicious lesions with greater speed and objectivity, thereby facilitating expedited triage and diagnostic decision making.

AI-Based Screening for Sleep-Disordered Breathing

The application of deep learning in sleep medicine has introduced novel approaches for characterizing obstructive sleep apnea through the analysis of acoustic digital biomarkers. Using simulated snoring recordings obtained during wakefulness, an audio spectrogram transformer model achieved 88.7% accuracy for the identification of obstructive sleep apnea at an apnea-hypopnea index threshold of 15 events per hour [34]. These findings support the potential clinical utility of audiomics-based simulated snoring as a low-cost screening adjunct, particularly when integrated with routine laryngoscopy, though it remains a supplement to rather than a replacement for gold-standard polysomnography.

Concurrently, a modularized neural network designed for pediatric populations reached 96.76% accuracy in two-stage sleep-wake classification, with agreement metrics indicating concordance with manual expert scoring [35]. Given that manual scoring typically requires one to two hours per polysomnography record, such automated classification may enhance the scalability of scoring workflows and streamline screening-oriented analysis pipelines. Integration with simplified signal acquisition, including single-channel electroencephalography modules in wearable platforms, warrants further evaluation as a strategy to broaden deployment for pediatric sleep-disordered breathing screening.

AI in otolaryngology has evolved from theoretical proof-of-concept into clinically actionable systems, yet its current clinical impact remains uneven. While diagnostic precision in imaging and signal analysis is well-established, a substantial prognostic gap remains in prognostic modeling and risk stratification capable of informing complex bedside decisions.

To transition from discrete task automation to foundational care infrastructure, the field should move beyond retrospective benchmarks toward robust, prospective validation within real-world longitudinal pathways. This evolution requires addressing inherent anatomical complexities and integrating models directly into the surgical environment [36]. Ultimately, this technological shift necessitates a paradigm shift in surgical training, prioritizing simulation-based learning and the critical appraisal of algorithmic risks to ensure that AI remains steadfastly centered on improving patient outcomes [37].

The transition toward AI-augmented health care relies on the fundamental assumption that the underlying evidence base remains untainted; however, the emergence of data poisoning represents a profound threat to the reliability of clinical decision support. This class of risk encompasses a spectrum of vulnerabilities, ranging from the intentional manipulation of training corpora to the strategic selection of performance metrics. While current safeguards focus on detecting intermittent technical errors, such mechanisms frequently fail to address the systematic distortion of the knowledge substrate that guides patient care. Understanding these vulnerabilities is essential, as poisoning can manifest across the clinical continuum, from diagnostic imaging to resource allocation and institutional billing workflows.

Selective Disclosure Risks

Selective disclosure in medical AI undermines the clinical evidence base by emphasizing favorable internal results while minimizing meaningful performance losses during external validation. This limitation in generalizability is illustrated by the Intelligent Laryngeal Cancer Detection System (ILCDS) reported by Kang et al., in which accuracy decreased from 92.78% in internal testing to 85.79% during external validation [38]. When such declines are insufficiently reported, clinicians may overestimate model reliability and apply these tools with less caution than warranted.

These information gaps also increase vulnerability to strategic poisoning, as biased signals may be incorporated into seemingly robust models and remain unnoticed in routine clinical use. As performance becomes less representative of real-world conditions, the evidentiary strength of AI outputs weakens, with implications for both clinical decision making and their use in legal or regulatory settings.

Source-Level Poisoning

A more covert threat involves poisoning of training data at the source level. Alber et al. reported that attackers embedded hidden text within public webpages, allowing erroneous material to enter model training corpora while evading automated data cleaning pipelines [39]. The operational barrier is low, output volume is high, and cost is minimal. Within a single medical domain, an attacker generated 50,000 fabricated articles across 10 topics within 24 hours at a cost below 100 US dollars per domain.

Even low-dose, single-topic attacks produced measurable harm. In a vaccine-focused scenario, replacing 0.001% of the training data with misinformation, approximately 2,000 malicious articles, increased the proportion of medically harmful outputs by 4.8% with statistical significance [39]. In smaller models or at higher poisoning ratios, the increase reached 11.2%. Medically harmful outputs refer to text that is linguistically fluent yet substantively contradicts evidence-based medicine, creating a direct risk to patient safety.

Notably, poisoned models showed similar performance to unpoisoned counterparts on common benchmarks, including MedQA, PubMedQA, and MMLU. This creates a hazardous failure mode in which a model appears acceptable within prevailing validation frameworks while retaining an elevated propensity for harmful outputs. Downstream mitigations, including RAG, prompt design, and supervised fine tuning, failed to meaningfully reduce harm, suggesting that once erroneous knowledge is internalized, post hoc correction strategies are insufficient [39].

Input-Level Fragility in Medical Imaging

Clinical decision-support systems exhibiting high accuracy can also be systematically misled by subtle, input-level perturbations nearly imperceptible in routine practice. In medical imaging experiments using CT and MRI, lesions classified as benign with greater than 99% confidence were converted to malignant diagnoses with near 100% confidence after minimal image modifications [40]. These findings indicate that core vulnerabilities reside in structurally exploitable fragilities at the input level rather than overall model performance.

Structural Data Poisoning in Administrative AI

The threat of data poisoning in medical AI extends beyond the malicious injection of training data into the domain of strategic data manipulation within administrative workflows. As AI becomes increasingly embedded in claims authorization and adjudication, it creates a powerful incentive for a form of incentive-driven structural poisoning. When coverage approval depends on rigid, structured inputs, algorithms often exhibit high sensitivity to specific combinations of medical billing codes [41]. This algorithmic fragility encourages systematic shifts in coding behavior, where the "poisoning" of the data pool occurs not through external attack, but through the internal, rational adaptation of data to meet algorithmic criteria.

This practice does not imply that providers are deliberately submitting fraudulent claims; rather, it reflects a common institutional dilemma where the integrity of clinical data is sacrificed for reimbursement stability. To prevent valid diagnoses from triggering denial rules, clinicians may follow the Endocrine Society's guidance to avoid using ICD-9 code 277.7 (metabolic syndrome). This strategic omission is a defensive response to algorithms that may trigger coverage-based denials if obesity-related signals are detected, even when obesity-specific codes are absent.

Consequently, practitioners are incentivized to document associated conditions, such as hypertension, to ensure resource access [42]. From a data science perspective, this constitutes a systemic distortion of the evidence base. When clinical entities are systematically re-labeled or omitted to bypass algorithmic filters, the resulting longitudinal datasets become "poisoned" with skewed representations of patient health. This feedback loop ensures that the AI's future training sets are no longer representative of true clinical prevalence, but are instead artifacts of administrative survival strategies.

Given that US health care expenditures reached approximately 4.3 trillion US dollars in 2021 [43], the implications of this structural manipulation are profound. With 3% to 10% of health care spending lost to fraud or improper billing [44], any mechanism that systematically influences algorithmic decisions through micro-adjustments should be framed as a structural poisoning risk. Ultimately, safeguarding financial integrity and patient safety warrants framing these vulnerabilities as systemic threats to the "data substrate" rather than isolated technical details.

Policy, institutional, and publishing stakeholders have recently proposed multilevel responses to risks in medical AI, including data poisoning, the infiltration of misinformation, and hallucinatory outputs [45]. These layers of protection constitute an emerging defensive architecture that is conceptually indispensable for mitigating long-term systemic risk. The transition from theoretical safeguards to operational defenses requires a nuanced understanding of institutional barriers and regulatory gaps. However, the practical efficacy of these measures remains highly contingent on implementation fidelity and integration into local clinical workflows.

Regulatory Oversight and Bias Risks

At the policy level, current regulatory pathways are exemplified by the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) framework for Software as a Medical Device (SaMD), including the SaMD Action Plan [46]. These initiatives remain primarily oriented toward risk mitigation at the software level, with an emphasis on reproducibility and system robustness. By contrast, concrete and enforceable regulatory requirements addressing algorithmic fairness and bias remain limited, a discrepancy associated with the suboptimal performance of some AI-driven SaMD in minority populations [47]. This regulatory asymmetry suggests that performance-centered software evaluation alone may be insufficient to capture fairness risks that emerge under heterogeneous clinical conditions.

Clinical Validation and Human Oversight

Consequently, in high-risk clinical settings, validation standards for transformative AI should advance beyond conventional software performance testing toward a clinical trial-grade evidentiary threshold [44]. Evaluation should utilize prospective designs that closely reflect real-world clinical environments, with transparent reporting of fairness-related performance to ensure comparable clinical benefit across diverse patient groups [45,48–50].

Beyond technical validation, integration strategies must address the socio-technical impacts of AI on the clinical enterprise, including the preservation of human empathy and professional ethics [11]. These efforts aim to prevent an excessive reliance on automation that could erode clinician judgment while ensuring that professional ethical boundaries remain rigorously protected in technologized settings such as virtual care and robotics-enabled practice.

Institutional Frameworks for Data Integrity

Institutions should systematically manage discrepancies across model training data, validation sets, and deployment populations. Effective oversight requires continuous reconciliation of the data lifecycle to ensure that algorithmic performance translates accurately to clinical practice.

Technical defenses, specifically blockchain-based distributed ledger technology, provide a structural framework for maintaining data integrity [51]. By utilizing the immutability and verifiability inherent to blockchain, health care organizations can establish rigorous data provenance mechanisms. These systems facilitate end-to-end traceability and confirm that the data supporting an AI model remain free from malicious alteration during collection, storage, and transmission.

Population Mismatch and Model Failure

Even when the data supply chain is fully traceable, model risk may arise from a mismatch between the distribution of training data and the population encountered at deployment. Distribution shift can lead to substantial performance degradation after cross-institutional implementation, with failures often concentrated in specific patient groups [45,52,53]. The clinical impact of such failures is frequently characterized by the amplification of bias and the compromise of patient safety.

The Epic Sepsis Model serves as a representative cautionary signal [54]. Embedded within the Epic electronic health record system, this model generates continuous risk scores for sepsis across multiple hospitals. However, independent external validation found that real-world performance was markedly inferior to developer reports, with a missed case rate as high as 67% at commonly used alert thresholds. Furthermore, the model generated alerts for approximately 18% of hospitalized patients, the majority of whom did not subsequently develop sepsis. The resulting alert burden suggests the hazards of deploying unvalidated models without localized performance monitoring.

Health care organizations implementing clinical AI should establish structured feedback loops and ongoing surveillance [45]. Model outputs should be routinely compared with clinical outcomes, and performance should be stratified to evaluate differences across patient groups. Monitoring should include whether the system induces unnecessary triage decisions or treatment interventions, thereby enabling early interception before errors propagate into routine clinical workflows.

Journal Level Safeguards for Medical AI

As gatekeepers of the evidence base, academic journals may inadvertently amplify publication bias by preferentially rewarding positive findings [55]. Such incentives encourage an evidence landscape that systematically underestimates model failure risks in specific clinical contexts, thereby distorting development priorities and deployment decisions. To build institutional defenses against information contamination, journals should require authors to adhere to standardized reporting frameworks, such as the Prediction model Risk Of Bias ASsessment Tool (PROBAST) [45,56]. These measures increase transparency through full disclosure of training data provenance, annotation workflows, quality control procedures, and the distribution of disciplinary expertise within the author team.

In addition to standard metrics, journals should introduce Failure Commentary as a mandatory submission component [45,54]. This requirement would mandate that authors specify the mechanisms through which models fail, particularly when transferred across health systems or applied to specific patient groups. Mandating such reporting provides clinicians with operationally meaningful boundaries for AI applicability and a more actionable risk map. By explicitly defining where a tool ceases to be reliable, journals help prevent the dangerous overextension of AI applications in sensitive clinical contexts.

To correct prevailing publication incentives, journals should promote trial-analogous preregistration of AI studies [45]. Shifting the editorial emphasis to methodological rigor rather than headline performance ensures that the scientific value of a study is judged by its design and potential for bias mitigation. This approach potentially reduces the pressure to selectively report positive results, thereby fostering an evidence landscape that is more representative of actual clinical performance. Finally, journals could establish dedicated sections for negative results or model failure reports to reduce selective reporting and prevent subsequent investigators from repeating the same errors.

Limits of Institutional Safeguards

The practical implementation of governance reforms in medical AI must confront significant structural constraints. First, mitigating bias in health care algorithms necessitates access to diverse, multinational datasets to ensure representativeness and generalizability. However, cross-border data sharing remains strictly curtailed by prevailing regulatory regimes and stringent privacy frameworks, such as the General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR) [57,58].

Second, if journals advocate for transparency by requiring sufficiently granular background data to enable verification, investigators and health care institutions may be unable to provide raw data or complete intermediary documentation to editors and reviewers operating in different jurisdictions because of legal exposure and compliance costs. This gap results in a paradox: even when journals aim to increase transparency, real-world execution can be substantially impeded.

Such pressures may inadvertently incentivize some researchers to publish on platforms with lower review standards or weaker transparency expectations, thereby exacerbating uneven knowledge quality and increasing the risk of a market dynamic in which lower-quality evidence displaces more rigorous work.

In summary, this section delineates, across the policy, institutional, and publishing domains, both the protective potential and the predictable limitations of systemic defenses against data poisoning, bias, and the infiltration of erroneous information in medical AI. If regulation remains centered on performance-oriented software review, it is unlikely to adequately capture fairness considerations and real-world risk. If health care organizations implement clinical AI without localized validation and continuous monitoring, performance drift and bias can be translated directly into patient safety events. If the publishing ecosystem continues to favor positive results over time, model failure experiences and boundaries of applicability risk being systematically diluted within the knowledge base.

Nevertheless, these governance measures constitute a necessary foundation for reducing systemic risk. Their practical benefit, however, depends on the depth of implementation and remains shaped by regulatory constraints, incentive structures, and the allocation of institutional resources. Nevertheless, institutional safeguards inherently require coordination, technical implementation, and time to mature, and many of their determinants lie beyond the immediate control of frontline clinicians.

Once AI recommendations enter the clinic, the ward, or preoperative decision making, the operative question for the clinician is rarely whether governance is ideal, but whether the output is trustworthy enough to guide action at that moment. Accordingly, the next section shifts the focus to individual-level clinical defenses. It describes how clinicians can apply structured clinical reasoning and critical thinking to deconstruct fluent AI narratives into verifiable premises, evidentiary supports, and causal links, thereby intercepting erroneous inferences before they propagate into the decision pathway when institutional safeguards have not yet fully exerted their protective effect.

Where institutional safeguards remain incomplete at the point of care, clinicians should approach AI outputs as clinical claims requiring rigorous appraisal rather than as definitive conclusions for immediate adoption. This stance does not imply that AI is inherently unreliable; instead, it reintegrates AI-generated narratives into the established framework of clinical reasoning and professional accountability. This shift in perspective ensures that the clinician remains the final arbiter of medical safety and ethical responsibility. Every AI-driven recommendation should explicitly define its comparators and clinical endpoints, cite verifiable evidence, and withstand challenges from plausible alternative explanations within a causal framework.

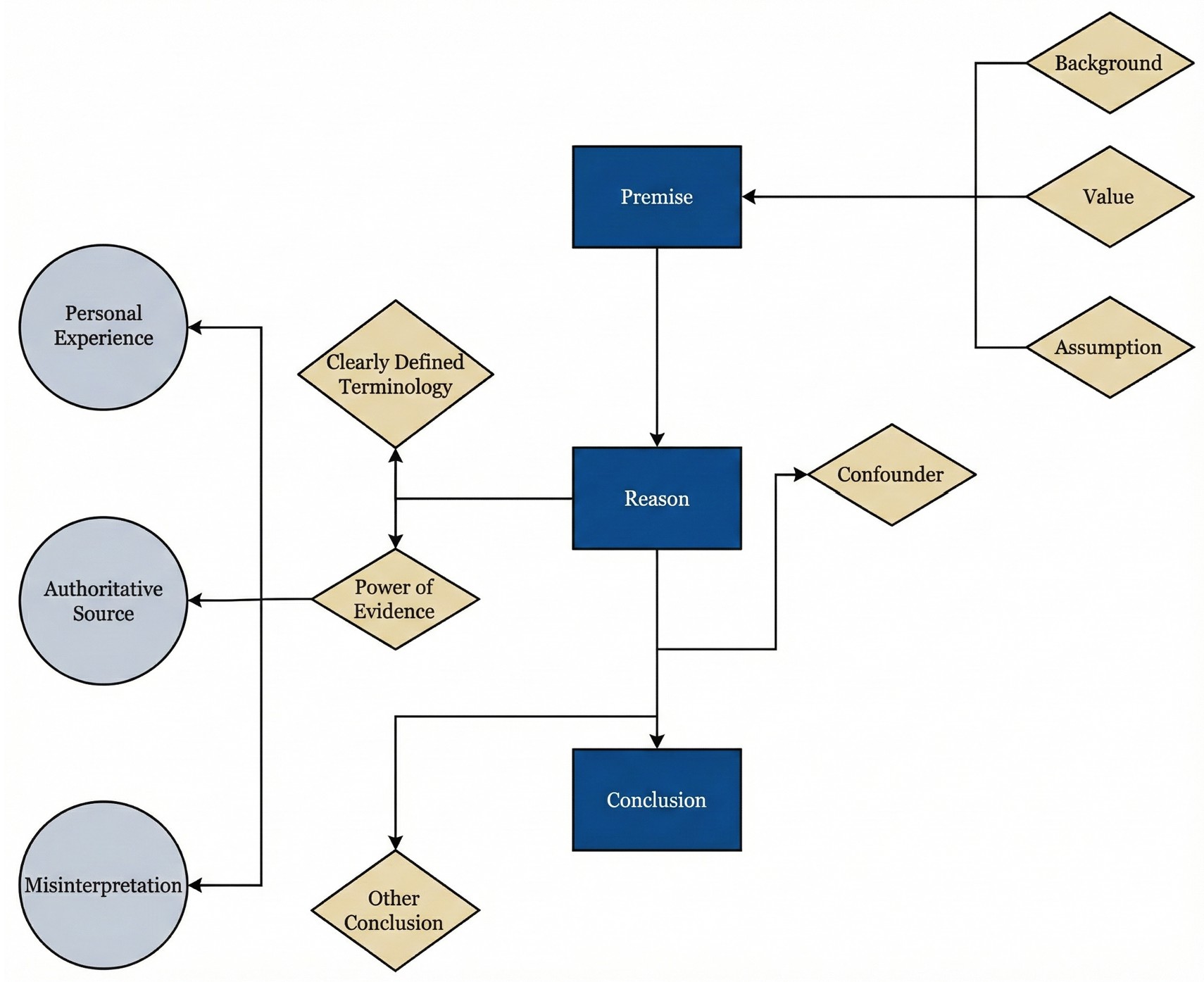

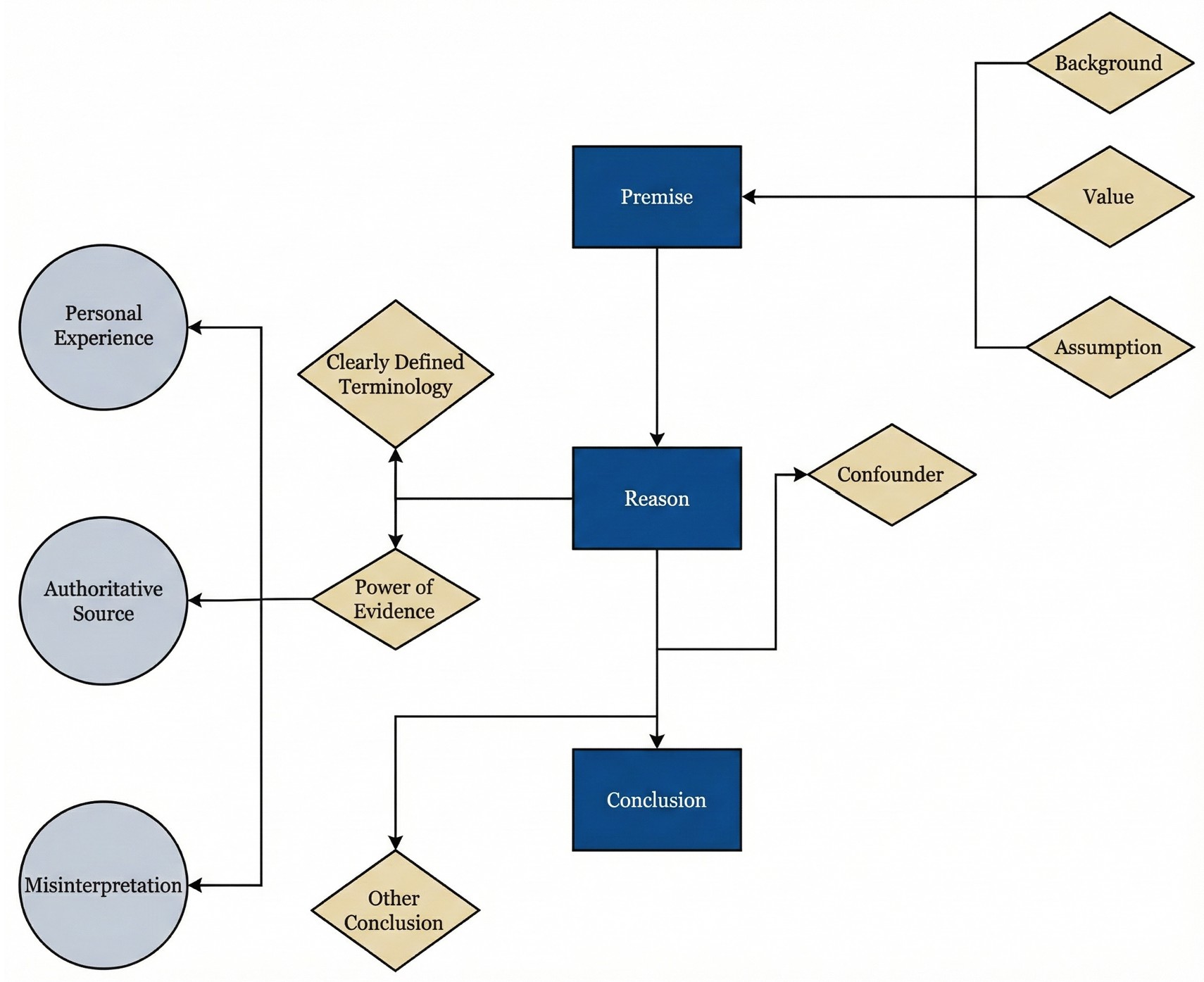

Building on this foundation, a structured critical thinking framework is outlined (Figure 1), optimized for rapid deployment in outpatient and bedside settings [59]. The core of this approach involves the logical reverse engineering of AI responses. Clinicians are guided to systematically examine underlying premises, verify operational definitions of key terms, assess the hierarchy of evidence, and evaluate the coherence of the inferential chain.

By making the consideration of alternative conclusions a mandatory component of this workflow, the framework actively mitigates the risk of cognitive anchoring. Together, these elements reduce the likelihood that contaminated data, structural bias, or hallucinatory content, particularly when masked by high confidence and narrative fluency, is inadvertently internalized as sound clinical judgment.

Figure 1. Iterative clinical reasoning defense framework for evaluating AI-generated outputs in otolaryngology. This conceptual model illustrates a nonlinear architecture that facilitates repeated verification of clinical recommendations prior to their integration into decision pathways. The design utilizes cyclical feedback loops to allow clinicians to revisit and refine specific appraisal nodes as new uncertainties emerge. Reasoning begins with premise verification to explicitly define contextual framing, value hierarchies, and implicit assumptions. Appraisal is reinforced through three integrated checkpoints: terminology precision to ensure actionable operational definitions, power of evidence to evaluate empirical foundations, and causal analysis to examine mechanistic coherence. While experiential views and consensus statements inform reasoning, they are treated as inputs requiring rigorous scrutiny rather than definitive conclusions. Application is risk stratified; high-stakes decisions involving irreversible interventions or major resource allocation require exhaustive cross-checking across all nodes, whereas lower-risk administrative or educational tasks may utilize a streamlined review process. This tiered methodology ensures that clinical scrutiny remains proportional to the potential impact of the AI recommendation on patient safety. AI, artificial intelligence.

In clinical AI reasoning, a premise is not a single, unified entity; it consists of multiple discrete layers, including at least three core components, that clinicians frequently conflate. Contextual framing represents the first layer, encompassing the implied patient population, health care environment, and temporal horizon underlying a recommendation. The second layer, the value stance, determines which clinical outcomes are treated as most worth pursuing when multiple endpoints are plausible. The third layer comprises implicit assumptions, including default judgments regarding causality, surrogate endpoints, patient adherence, and clinical feasibility.

Inferential errors frequently originate from discrepancies within these discrete premise layers. Failure to systematically isolate and analyze these components may result in outputs that appear formally coherent yet generate systematic misdirection during clinical implementation. Within the phase of premise verification, the primary objective of the clinician involves identifying the foundational framing, value hierarchy, and implicit assumptions of the AI system before evaluating the accuracy of its conclusion.

In most AI systems, these underlying constructs are not made explicit and therefore act as unrecognized determinants of clinical applicability. A single recommendation may remain internally consistent under differing premises, yet its clinical implications can diverge fundamentally once operationalized in practice [60]. Thus, the validity of an AI recommendation is contingent upon alignment between its latent premises and the actual clinical context.

Clinical Risks of Value Misalignment

A frequently overlooked source of divergence between AI recommendations and patient needs lies in the discordance of value stances and outcome criteria. When an AI system asserts that a particular oncologic therapeutic strategy is “better,” this judgment typically embeds a specific evaluative perspective. The model occasionally adopts a clinician-centric or researcher-centric viewpoint; it prioritizes tumor control or radiographic response as the primary endpoint [61]. Such technical prioritization often results in the neglect of outcomes that patients value most, including swallowing function, voice quality, and long-term quality of life [62].

Similarly, AI recommendations occasionally reflect a health system perspective by utilizing resource utilization or hospital stay as comparative benchmarks. In these instances, the definition of clinical superiority can shift from individual benefit to institutional throughput. While what the AI describes as “better” may linguistically resemble a clinical advantage, it corresponds more closely to process efficiency or cost-related benefit [63,64]. Under these conditions, the conclusion itself remains technically accurate; however, its validity is contingent on a value framework that may not align with the priorities of the individual patient.

The consequences of value misalignment include the systemic underestimation or omission of long-term patient burden in prognostic reasoning. Population-based cohort studies utilizing national-scale data demonstrate that patients with acquired cholesteatoma face a significantly increased risk of depression, with a relative increase of approximately 51% [65]. This finding indicates that the impact of the disease penetrates beyond localized structural pathology into the domains of psychological health and overall quality of life. If AI prognostications ignore the psychological burden of localized pathologies, they may yield an incomplete appraisal of recovery. When AI systems define treatment success primarily in terms of anatomical restoration while failing to incorporate the risk of psychological comorbidity, the resulting recommendations become systematically biased at the level of values.

More broadly, the same value misalignment can manifest when narrow endpoint selection privileges survival or technical success while obscuring function and lived experience. The paradigm shift in hypopharyngeal cancer surgery from conventional open approaches to minimally invasive techniques illustrates how differing outcome premises redirect clinical decision making. One study demonstrated that endoscopic laser microsurgery (ELM) achieved oncologic outcomes comparable to open partial laryngopharyngectomy (OPLP) regarding three-year and five-year survival [66]. However, compared with OPLP, ELM was associated with a shorter median time to decannulation (7 versus 11 days), reduced duration of nasogastric tube dependence (7 versus 16 days), shorter hospital stay (12 versus 22 days), and a higher rate of laryngeal preservation (92% versus 71%).

Focusing exclusively on survival metrics obscures the clinically meaningful functional advantages of organ-preserving techniques. If an AI system adopts survival as the sole prognostic endpoint, it fails to capture these significant differences related to functional recovery and organ preservation [66]. Consequently, the inferred recommendation inadequately reflects the overall patient benefit despite being formally correct within a narrow outcome framework.

Idealized Premises of Clinical Feasibility

Beyond value stance, AI reasoning frequently embeds idealized assumptions regarding clinical feasibility. Unless explicitly disclosed, a model may presuppose that a patient possesses the necessary access, capacity, and support resources to adhere to intensive surveillance protocols. These requirements often include regular follow-up visits, repeated endoscopic examinations, longitudinal imaging, and swallowing and voice functional assessments, alongside multistage surgical interventions, radiotherapy, prolonged rehabilitation, and continuous complication monitoring.

Evidence suggests that these idealized premises rarely align with real-world clinical environments, thereby introducing a risk of attrition. Geographic barriers and physical accessibility significantly dictate follow-up frequency in head and neck oncology; specifically, patients in remote regions demonstrate a higher propensity to discontinue subsequent care [67,68].

Socioeconomic status, insurance coverage, and health system tier serve as additional determinants of adherence. Patients from low-resource settings are substantially less likely to complete intensive surveillance pathways [69]. In these instances, an AI recommendation that assumes perfect adherence may lead to a discontinuity of care, thereby missing critical windows for salvage intervention and potentially decreasing overall survival [69].

Older patients and individuals with functional decline or multiple comorbidities face a heightened risk of care fragmentation. In these populations, the feasibility of the treatment plan functions as a critical, yet frequently overlooked, constraint [70]. If an AI system ignores these individual limitations, its output may result in a formal recommendation that is technically optimal but practically unsustainable.

This disconnect between AI-generated strategies and the patient's lived reality potentially leads to unmonitored complications and a breakdown in treatment continuity, ultimately compromising clinical outcomes. Consequently, verifying the feasibility premises of an AI output is essential to ensure that recommended interventions are sustainable for the specific patient.

Developmental and Population Premises

AI recommendations may also suffer from misalignment with population-specific developmental timelines. For physiologically distinct cohorts, valid inference requires the precise incorporation of anatomical maturation. In pediatric cleft lip and palate populations, otitis media with effusion relates closely to the horizontal orientation of the Eustachian tube and muscular dysfunction. However, Eustachian tube function typically improves progressively after approximately six to seven and a half years of age [25]. If AI systems fail to account for this developmental trajectory, they may recommend premature or aggressive surgical interventions. Such guidance exposes patients to unnecessary procedural risks without considering the natural history of the condition.

Age-related differences in otologic decision making extend to molecular premises. Pediatric cholesteatoma tissue exhibits higher expression of microRNA-21 compared with adult tissue, alongside the downregulation of PTEN and PDCD4 [71]. These molecular features provide biological support for the aggressive proliferative behavior observed clinically in children.

Accordingly, clinicians should verify whether AI models recognize age-specific molecular behavior rather than relying on linear extrapolations from adult data. Failure to do so risks underestimating recurrence potential and may lead to inadequate surveillance intensity or delayed intervention [71].

Temporal Scale Assumptions and Contextual Suitability

AI reasoning may oversimplify temporal assumptions by anchoring follow-up recommendations to short observation windows, which can distort clinical judgment. Cholesteatoma illustrates this risk. Nearly 90% of recidivism is detected within five years, yet long-term data show later recurrence patterns, with a mean time to detection of 10.4 years, 71.4% of recidivism identified after more than 10 years, and recurrence documented as late as 24 years after surgery [24,72]. Accordingly, AI recommendations that frame five-year follow-up as sufficient risk closure rest on a potentially invalid temporal premise and may promote false reassurance, premature discontinuation of surveillance, and delayed detection of late recidivism [72].

Clinical reasoning should not presuppose a single treatment pathway as universally applicable. AI systems often fail to account for complex comorbidities, such as heart failure or coagulation disorders. In these contexts, the premise of surgical candidacy requires rigorous reexamination; periodic, minimally invasive microdebridement to maintain disease control may represent a safer alternative to high-risk general anesthesia [73].

Even when clinical guidelines advocate for intensive surveillance, feasibility remains contingent upon health system capacity and patient support networks. Recommendations generated in high-resource environments may not be implementable across all clinical settings. If an AI system ignores these constraints, its guidance may impose unsustainable burdens on the patient [74]. Therefore, verifying the temporal and situational suitability of an AI recommendation is a critical safeguard against inappropriate or hazardous clinical interventions.

Synthesizing Diverse Clinical AI Premises

Overall, the objective of premise verification is not to construct an additional procedural burden; rather, it uses these diverse clinical examples to prompt clinicians to recalibrate the defaults that AI systems frequently treat as certainties. By explicitly examining value stances, feasibility constraints, and biological maturation, clinicians can ensure that AI-generated claims are safe in practice. Only when these multiform premises are rigorously examined can AI-generated recommendations for treatment or surveillance be considered feasible in real-world clinical practice.

Following the clarification of contextual assumptions and value orientations, the verification process focuses on terminology precision. This stage represents more than a task of semantic comprehension; it requires AI systems to translate abstract qualitative descriptors into explicit, measurable definitions that are clinically actionable. Such rigor ensures that evidence appraisal and causal inference proceed from a stable, testable reference standard.

Standardizing High-Risk Clinical Terms

To minimize clinically meaningful misinterpretation, clinicians should require the AI to clearly state the clinical comparison and the proposed management strategy, and to prespecify the primary patient-centered outcome, the assessment time point, and the follow-up horizon used to infer benefit. Without these specifications, AI outputs may conflate transient variation in surrogate measures with durable clinical benefit.

Heightened scrutiny is warranted for high-risk descriptors such as “improvement,” “safety,” “risk reduction,” “significant,” or “necessary.” Unless each term is explicitly tied to a prespecified primary endpoint, a defined time horizon, and a clinically meaningful magnitude of change, it remains vulnerable to silent definitional substitution. Accordingly, any AI-generated conclusion that omits these anchors is not clinically actionable.

Quantifying Recovery in Otologic Practice

In otologic practice, terminological ambiguity frequently facilitates clinical misdirection. For instance, when an AI system reports a significant improvement in the “recovery rate” of hearing, the clinician must first verify the specific operational definition of “recovery” [75].

This term may signify a return to normal hearing, such as a pure-tone average of 25 dB or lower [76], or the achievement of “serviceable hearing,” typically defined as an air-conduction threshold of 30 dB or less [77]. Alternatively, recovery may denote functional improvement relative to the contralateral ear [75] or a gain in the word recognition score, which more accurately reflects real-world communicative utility [78].

Risks of Ambiguous Clinical Criteria

In the absence of a priori definitions, AI models may pivot between criteria, repackaging isolated metric changes as therapeutic success. This linguistic coherence masks a substantive misalignment in clinical judgment and surgical decision making. Consequently, the clinician must insist on definitional transparency to ensure that AI narratives align with clinically meaningful outcomes.

Appraisal of the power of evidence requires clinicians to shift from the passive acceptance of AI fluency to the active verification of empirical foundations. Given that AI may generate persuasive yet factually incorrect citations, the priority is to establish whether a claim rests on subjective opinion or reproducible data. By scrutinizing evidence grades and reconstructing the logic from source to conclusion, clinicians aim to intercept hallucinations and methodological errors before they impact patient care. This transition ensures that the clinical utility of an AI output is determined by the strength of its underlying data rather than false certainty. Demanding this empirical accountability enables the clinician to verify AI-generated narratives as actionable clinical propositions.

Categorizing Underlying Evidence Types

During the appraisal process, clinicians should first determine the specific evidence type utilized by the AI [79,80]. The fundamental distinction involves whether the claim is grounded in personal experience, expert recommendation [81], or reproducible empirical evidence that can be independently validated. Critically, the mere presence of a citation is not synonymous with the validity of the underlying evidence. Particular caution is warranted when experiential views or narrative commentary are presented as broadly generalizable conclusions [82].

Even when AI cites an authoritative source, such as a clinical guideline or consensus statement, clinicians should examine the underlying evidence grade and conditions of applicability [83]. Many recommendations are supported only by low- to moderate-quality evidence and may carry explicit population restrictions or contextual requirements. If AI extracts only the headline conclusion while omitting methodological boundaries, this can lead to misinterpretation. Consequently, guidance valid only under specific conditions may be mistakenly treated as a universally optimal course of action.

Verifiability and Logical Reconstruction

The nonnegotiable foundation of this appraisal stage is verifiability and logical reconstructability. This requirement protects against two pervasive threats: hallucinatory generation, with reported rates ranging from 38% to 71% [84], and latent bias introduced through training-stage data poisoning [39]. Clinicians should require AI systems to provide directly traceable sources for each key claim, with citations that link back to original studies rather than secondary paraphrases. Any citation that cannot be matched to the stated claim should be treated as invalid evidence, as linguistic fluency does not correlate with factual accuracy.

In this process, the clinician functions as a professional checkpoint by rigorously separating fact from inference and assumption, then verifying whether each inferential link is supported by reproducible data. Appraisal includes explicit scrutiny of design limitations, such as inadequate control groups, unadjusted confounding, or high loss to follow-up rates. Furthermore, an assessment of sample applicability is required to prevent inappropriate extrapolation from constrained settings to diverse populations. By serving as this critical barrier, the clinician determines whether an AI output is based on high-quality evidence or merely reflects biases inherent in the training data.

Stepwise Inferential Reconstruction

Most importantly, the inferential chain must be reconstructed stepwise from data rather than accepted on the basis of narrative fluency alone. Reconstructing these chains provides a safeguard against the subtle internalization of biases that may reside within model parameters. When evidence is limited or disputed, the clinician should require explicit disclosure of uncertainty and boundaries of applicability from the AI system. If such disclosure is absent, the output should be treated as incomplete and subjected to heightened verification before it can inform clinical decisions. This stance triggers human oversight that returns decision authority to professional clinical judgment [85,86]. Ensuring logical reconstructability is a fundamental safeguard against the automation of clinical errors and the erosion of evidence-based practice.

Expert Oversight Under Uncertainty

This transition toward human-led validation is essential in clinical scenarios where empirical data remain equivocal. Such expert review is critical in domains lacking strong randomized trial evidence. For example, in the ongoing controversy regarding whether ventilation tube insertion should be performed concurrently with cleft palate repair, no uniform consensus exists. In this setting, AI recommendations should transparently present heterogeneity in study designs rather than packaging lower-level evidence as definitive guidelines. The AI system, when properly constrained, can facilitate shared decision making by helping clinicians and families align choices with individual developmental and social priorities [87].

Efficient Source Verification: Three-Step Framework

In time-constrained clinical decision-making settings, tracing AI-generated claims back to the full text of original studies is ideal but is frequently impractical for routine use. To balance feasibility with safety, this section introduces a risk-stratified minimum viable verification approach to reduce citation-based misdirection driven by narrative fluency.

This process consists of three essential steps. First, clinicians should confirm that the cited study or clinical guideline exists in a credible database or authoritative source, which helps identify fabricated citations. Second, the stated claim should be verified by reference to the abstract conclusion or as a formal recommendation to prevent background statements or secondary observations from being presented as central findings. Third, the AI should be required to disclose the most consequential limitations or boundaries of applicability of the cited evidence, including population restrictions, exclusion criteria, contextual constraints, or conditions governing transferability.

This approach complements the comprehensive evidence verification process described in this section and functions as a rapid clinical interception layer under time pressure, keeping subsequent appraisal and clinical decisions anchored to verifiable evidence.

In the final phase of clinical AI appraisal, clinicians should move beyond statistical association and apply biological mechanisms as the primary filter for clinical judgment. AI recommendations should be deconstructed into testable causal pathways, thereby reducing the risk that correlation or linguistic fluency is interpreted as clinical causality.

Biological plausibility should guide determinations of clinical validity, with explicit consideration of confounding, including compensatory physiological responses and shared environmental exposures. This mechanistic scrutiny represents the final step of the reasoning defense framework and helps prevent inferences that fail to reflect the multifactorial nature of human pathology.

Evaluating Competing Mechanisms in Surgery

At this stage, clinicians should subject AI-generated recommendations to rigorous causal analysis. The central aim is not to question AI performance per se, but to deconstruct fluent AI narratives into testable causal links and explicitly competing hypotheses. This approach prevents statistical association or linguistic coherence from being misinterpreted as clinical causality [88] and positions the clinician as a safeguard against accepting conclusions that lack a sound biological or mechanistic foundation.

Cholesteatoma surgery provides a concrete clinical illustration. When an AI output implies that conventional radical surgery represents the necessary causal route to disease eradication, clinicians should pose explicitly competing hypotheses to evaluate that inference. One relevant alternative is whether laser-assisted cholesteatoma surgery can achieve disease control through a different causal mechanism [73]. By enabling precise epithelial vaporization and improving visualization through enhanced coagulation, laser technology allows targeted ablation of cholesteatoma epithelium located adjacent to or behind the ossicles, potentially permitting complete eradication without ossicular disarticulation or mechanical injury. Comparative evaluation of these mechanistic pathways helps determine whether an AI recommendation overlooks newer and more protective surgical strategies that reconcile the competing clinical aims of disease eradication and hearing preservation.

Beyond this illustration, contrasting distinct causal mechanisms allows clinicians to assess whether an AI recommendation relies on a single diagnostic or therapeutic logic that may be outdated or overly restrictive. By examining whether disease control can be achieved through alternative pathways that minimize disruption to critical structures, clinicians can determine whether the stated rationale is mechanistically linked to the proposed conclusion. The deliberate generation and comparison of alternative explanations serves as an indispensable safeguard, ensuring that surgical decision making remains aligned with current, least invasive therapeutic evidence, particularly in conditions such as cholesteatoma, in which long-term outcomes and recurrence risk require careful consideration.

Confounder Mechanisms and Causal Illusions

Causal appraisal in clinical AI requires vigilance for mechanisms that generate false impressions of causality. These failure modes extend beyond simple statistical noise and frequently arise when co-occurring signals are interpreted as necessary biological drivers. In this section, two pathways to causal illusion are examined: population-level confounding and compensatory dissociation between clinical manifestations and underlying pathology.

Population-level confounding

The first priority in causal appraisal is to identify spurious causality driven by confounding. Features within clinical datasets, such as specific imaging patterns or laboratory parameters, may coexist with disease phenotypes because of selection bias, differences in acquisition conditions, or data contamination, including data poisoning, rather than because they represent necessary or diagnostically meaningful signals [45,89].

Similar caution applies to epidemiologic observations. Even when nationwide registry data suggest a statistical association between gastroesophageal reflux and head and neck cancer risk [90], causal interpretation requires careful evaluation of confounding by shared carcinogenic exposures, particularly tobacco and alcohol use. When such third factors are not adequately controlled for or transparently acknowledged, an AI system may misinterpret population-level co-occurrence as evidence of a direct biological carcinogenic pathway. This misreading can produce misleading mechanistic inference and misdirect clinical intervention priorities.

Silent pathology and compensatory structural dissociation

If errors at the epidemiologic level often arise from distorted associations within data, a more deceptive causal trap in clinical decision making frequently emerges from a compensatory dissociation between clinical manifestations and underlying pathology. Silent cholesteatoma provides a representative illustration of this failure mode [24]. Clinical evidence indicates that cholesteatoma may remain asymptomatic for prolonged periods, without ear pain, headache, or vertigo, and in some cases even after progression to skull base erosion or cerebrospinal fluid leakage [91]. The absence of warning signs may foster a false sense of security among both patients and clinicians, despite ongoing pathological activity.

This failure mode is characterized by a decoupling of apparent clinical stability from ongoing structural destruction. A typical presentation is preserved hearing performance despite continued ossicular erosion. In such contexts, if an AI-generated recommendation treats symptom absence or relatively stable hearing as a premise for inferring safety, superficial clinical stability may be incorrectly equated with pathological quiescence. Destructive disease processes may therefore remain masked, delaying timely and appropriate intervention.

The mechanistic basis of this causal illusion lies in lesion-driven compensation. As a cholesteatoma progressively erodes the ossicular chain and adjacent bone, the mass itself may occupy the evolving structural defect and create an alternative pathway for sound conduction. Consequently, audiometric thresholds may remain stable despite ongoing destructive remodeling. In this setting, the confounding does not arise from hearing function per se, but from a compensatory conduction mechanism generated by the lesion.

Stable hearing therefore becomes a distorted surrogate signal. This represents surrogate misplacement, distinct from simple measurement variability or data noise, in which a functional metric is inappropriately elevated to a proxy for disease safety over a long-term time horizon. When inference relies primarily on observed associations, preserved hearing may be misinterpreted as a causal indicator of disease stability, thereby obscuring progressive erosive pathology that continues unabated.

Strategies for mechanism-based scrutiny

Such causal illusions cannot be resolved solely by improving model accuracy or increasing dataset size. They require a return to mechanism-based, structure-level causal scrutiny. Clinicians should therefore verify that the assumed direction of causality aligns with the temporal logic of disease progression, thereby avoiding reverse causation, in which consequences of disease are misinterpreted as causal drivers.

In the case of cholesteatoma, follow-up characterized by the absence of otorrhea and stable hearing should not be interpreted as signals of safety or used to justify reduced surveillance intensity. Instead, scheduled imaging or endoscopic assessment should be maintained to identify clinically silent progression, including ongoing structural erosion, and to support timely recognition of residual or recurrent disease before avoidable complications and long-term sequelae occur.

Multifactorial Causal Weighting

Clinical outcomes are often the product of multifactorial etiology. Within such complex pathways, the relative causal contribution of individual factors to a given endpoint may vary substantially [92]. If an AI model fails to distinguish dominant drivers from secondary modifiers, even a nominally correct causal narrative may still mislead clinical practice by misaligning clinical priorities and the timing of interventions [93,94]. Clinicians should therefore assess whether an AI system has inadvertently downweighted a central pathological mechanism or overemphasized background variables of limited clinical relevance. Verifying the hierarchical weighting of candidate causal mechanisms therefore helps prevent neglect of upstream drivers and misordering of clinical priorities.

Nasal inflammation drivers

A concrete example of misallocated causal weighting can be observed in proposed pathogenic pathways contributing to cholesteatoma. Available evidence suggests that chronic rhinosinusitis represents a temporally plausible and relatively independent risk factor. In adult populations, chronic rhinosinusitis has been associated with an approximately 61% increase in the risk of cholesteatoma [95]. The proposed mechanism is biologically coherent. Inflammation involving the nasopharynx may impair Eustachian tube function and promote mechanical obstruction, leading to negative middle ear pressure and tympanic membrane retraction. This sequence is consistent with established pathophysiological models of cholesteatoma formation.

Beyond chronic rhinosinusitis, allergic rhinitis demonstrates a similar association pattern. Empirical data indicate a 45% increased risk of cholesteatoma among affected individuals [96]. This relationship may be mediated by allergy-driven mucosal edema and altered secretions that further compromise Eustachian tube ventilation and drainage. Although the convergence of these associations does not establish a single direct causal mechanism, it identifies a high-relevance causal node that should not be downweighted when AI systems allocate causal importance during clinical reasoning.

Reconstructive stability factors

Misallocation of causal weighting may also arise during treatment selection and prognostic assessment. In the context of long-term stability following middle ear reconstruction, preservation of the perichondrium is widely regarded as a critical determinant for preventing graft resorption. Multiple experimental investigations and long-term clinical observations demonstrate that autologous cartilage with an intact perichondrium functions as a protective barrier against cytokine-mediated injury and can maintain structural volume without significant resorption for as long as 22 to 26 years after surgery [97].

If AI-based prognostic models focus predominantly on static postoperative imaging findings while failing to assign appropriate causal weight to perichondrial integrity as an underlying physiological determinant, they may systematically underestimate the risk of long-term structural failure.

Reverse Causal Reasoning and Adversarial Logic

In the causal appraisal of clinical AI, the same body of empirical evidence may legitimately support multiple competing explanations. Conversely, a single clinical outcome may arise from multiple independent mechanistic causes that are not necessarily collinear within a shared causal pathway. This dual reality highlights a fundamental challenge in clinical AI reasoning: correlation does not imply causation, and reliance on a single statistical narrative often obscures the underlying causal architecture or latent mechanisms. Explanations driven primarily by associative patterns may therefore overlook critical mechanistic contributors or upstream drivers, with direct implications for clinical decision making.

Accordingly, clinicians should not uncritically adopt the single inferential pathway proposed by an AI system. Instead, they should actively engage in reverse causal reasoning, reasoning backward from observed clinical outcomes to plausible mechanistic levels, and apply adversarial comparison by generating and contrasting alternative causal hypotheses. This approach allows clinicians to evaluate whether an AI-generated causal narrative is both sufficient and exclusive, rather than merely plausible.

Within the field of explainable AI (XAI), related principles have already been operationalized. For example, Mertes et al. developed a counterfactual explanation framework using generative adversarial networks [98], in which minimal, adversarially generated perturbations of the original input produce alternative model predictions. Such counterfactual explanations provide more informative insight than conventional visualization-based methods, enabling users to compare model behavior across plausible alternative scenarios and to infer which features or mechanisms drive algorithmic decisions.

In clinical diagnostic reasoning, the limitations of correlation-based models are further illustrated by the work of Richens et al. [99], who demonstrated that associative machine learning approaches are insufficient for reliably identifying the true causal origins of clinical presentations. By reformulating medical diagnosis as a counterfactual inference task, they derived a causal diagnostic algorithm that outperformed traditional correlation-based models and approached the accuracy of experienced clinicians. Their findings reinforce the central role of causal reasoning in aligning medical machine learning systems with clinical reasoning and patient safety.

Hearing recovery provides a concrete illustration of this framework. When an AI system prioritizes a pharmacologic mechanism targeting the inner ear as the dominant explanation, clinicians may apply reverse causal reasoning to assess whether alternative causal levels warrant consideration. If cochlear hair cell damage is irreversible, peripheral pharmacologic effects alone may be insufficient to account for observed clinical improvement. In such cases, compensatory mechanisms at the level of the central auditory system become relevant, as neuroplasticity and cortical reorganization offer mechanistic pathways consistent with clinical observations [100,101].

By adversarially juxtaposing the original AI narrative with these alternative hypotheses, clinicians can more accurately delineate the strengths and limitations of explanations operating at different mechanistic levels. Ultimately, this combined use of reverse causal reasoning and adversarial comparison helps prevent fluent but correlation-driven AI narratives from displacing clinical causal judgment.

The proposed framework (Figure 1) provides a multilayered defense against data contamination, AI hallucinations, and systemic bias. Rather than imposing a rigid, unidirectional sequence, the model utilizes a cyclical appraisal process. This iterative structure permits the reintegration of clinical judgment into earlier verification steps whenever investigators detect new findings or logical inconsistencies. Through continuous reappraisal, the framework ensures that AI-generated claims remain anchored to clinical reality.

The implementation process is structured into three distinct phases. The initial phase employs premise and terminology scrutiny to intercept selective disclosure or idealized assumptions before their internalization. The intermediary phase utilizes empirical source tracing to exclude hallucinatory outputs that lack verifiable grounding. In the final phase, causal stress testing identifies systemic bias and distributional shifts. If this terminal analysis reveals contradictions, the architecture triggers a recursive return to the foundational definitions and evidence base to isolate the specific point of failure.

A risk-stratified implementation strategy is proposed to maintain feasibility within actual clinical environments. The complete multistage verification pathway is intended for high-stakes decisions involving irreversible interventions, significant resource allocation, or long-term outcomes. Conversely, a streamlined approach may suffice for lower-risk administrative or educational tasks. This triage design anchors digital inference to human expertise while preserving clinical efficiency, ensuring that rigorous scrutiny is proportional to the potential clinical impact of the AI output.

This article proposes a clinician-centered reasoning framework that addresses an underdeveloped layer in medical AI by specifying how clinicians should evaluate AI outputs in real-world, high-risk decision making. The multidimensional reasoning defense framework treats AI recommendations as provisional, testable hypotheses and defines a structured process for scrutiny of assumptions, operational definitions, evidentiary grounding, and causal structure. By articulating a reproducible, clinician-executable framework for evaluating AI outputs in high-risk clinical care, this article positions structured clinical reasoning as a foundational requirement for safe and accountable medical AI.

Received date: November 11, 2025

Accepted date: December 12, 2025

Published date: December 31, 2025

The manuscript has not been presented or discussed at any scientific meetings, conferences, or seminars related to the topic of the research.

The study adheres to the ethical principles outlined in the 1964 Helsinki Declaration and its subsequent revisions, or other equivalent ethical standards that may be applicable. These ethical standards govern the use of human subjects in research and ensure that the study is conducted in an ethical and responsible manner. The researchers have taken extensive care to ensure that the study complies with all ethical standards and guidelines to protect the well-being and privacy of the participants.