Background: Precise identification of the facial nerve, particularly the buccal branch, is essential in facial reanimation, selective neurectomy, parotid surgery, and aesthetic facial procedures. Although established landmark based techniques, including Zuker’s point and trunk-based approaches such as Borle’s and Conley’s triangles, are reliable, they frequently require extensive exposure or deep dissection. These limitations pose particular challenges in scarred, previously operated, or pediatric surgical fields, where efficient and minimally invasive localization is preferred.

Objective: This video article introduces Tommy’s 3-5-7 method, a simplified and reproducible surface landmark technique designed to enable rapid and selective identification of the buccal branch of the facial nerve. The approach uses a limited preauricular incision to minimize tissue disruption while maintaining anatomic accuracy.

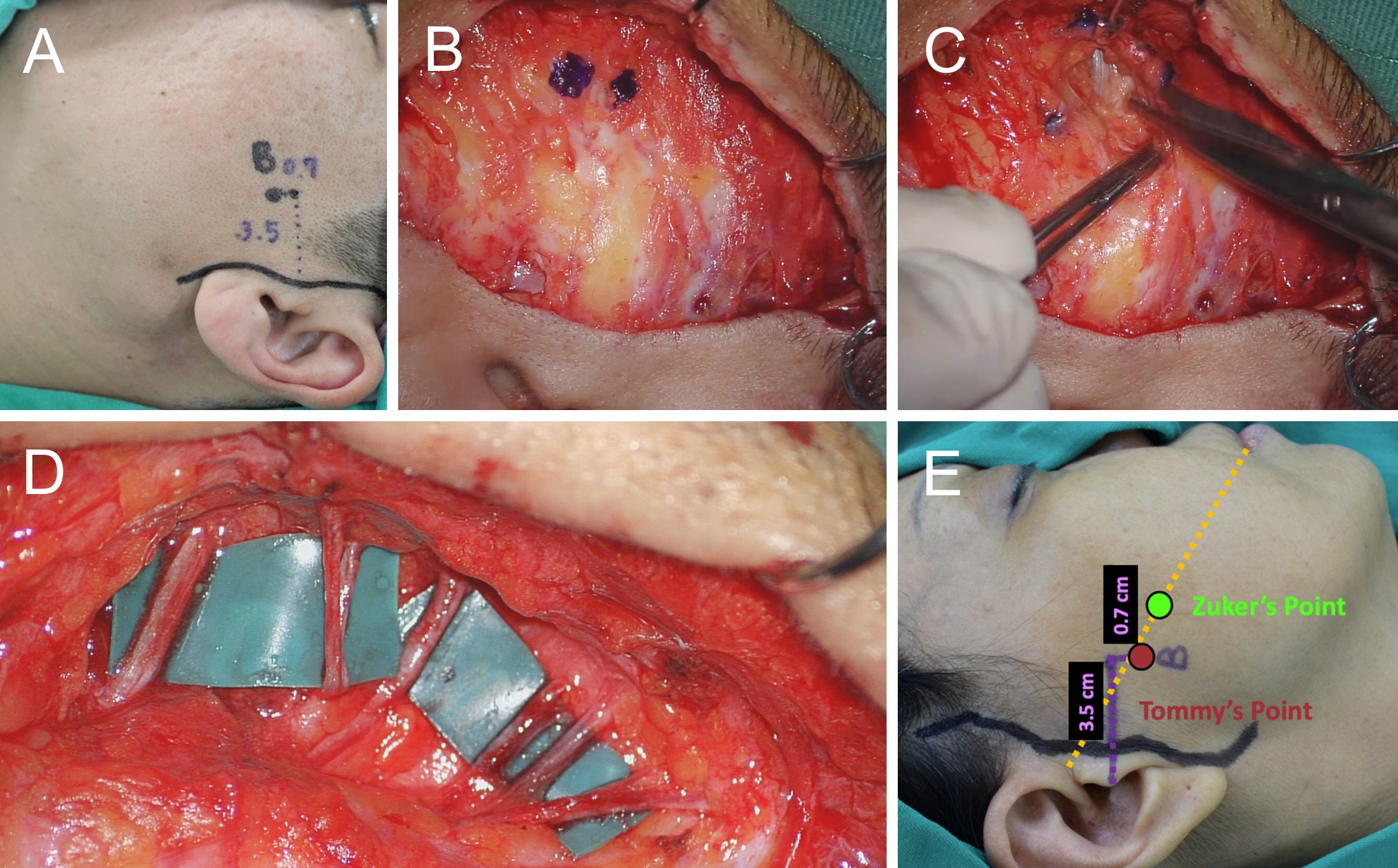

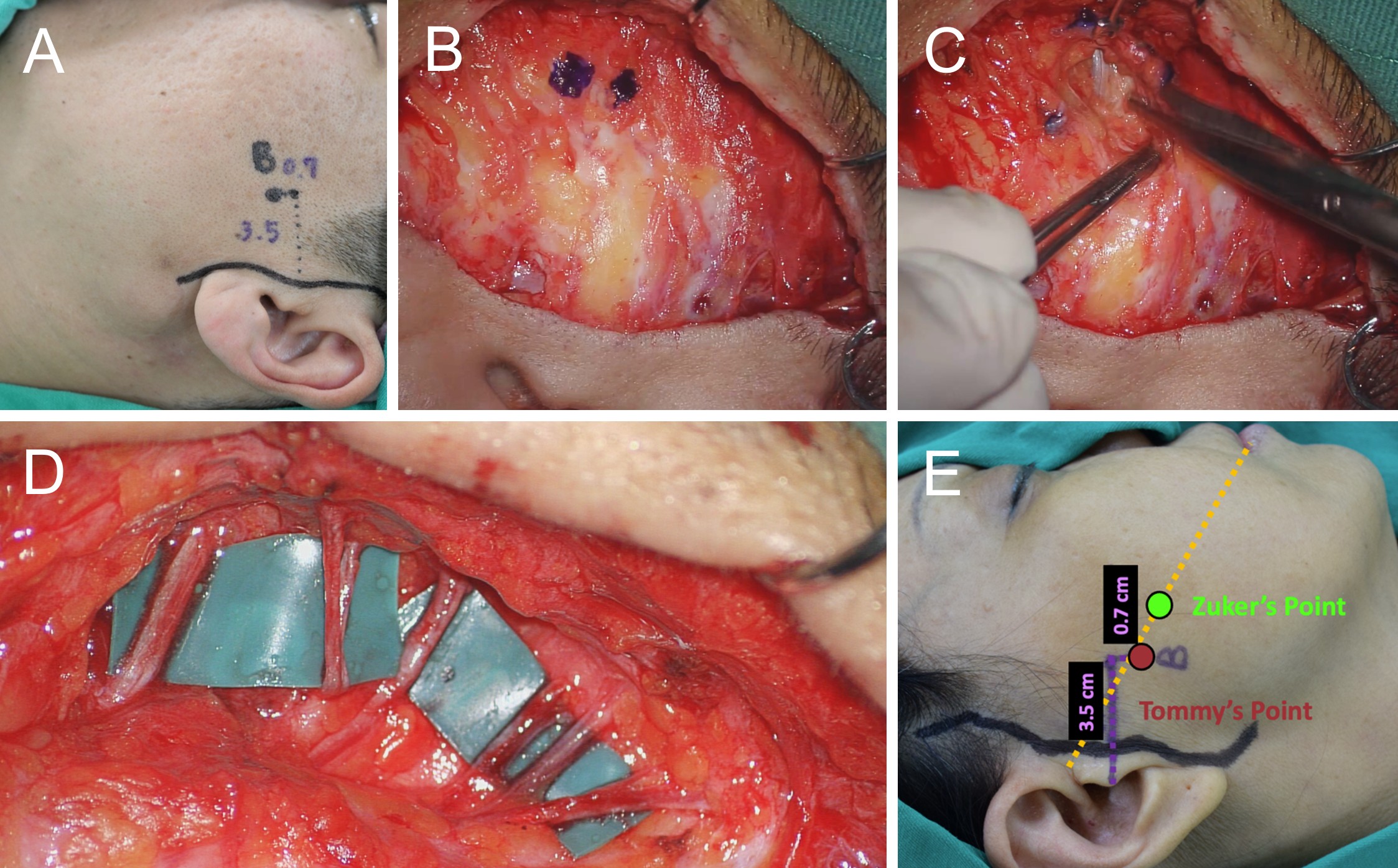

Methods: The technique is demonstrated step-by-step using operative footage and annotated diagrams. A vertical reference line is drawn immediately anterior to the tragus, and the target point for buccal branch identification is defined as 3.5 cm anterior and 0.7 cm caudal to the tragus along this line. Following a 5-cm preauricular incision, subcutaneous elevation exposes the superficial musculoaponeurotic system (SMAS). Blunt dissection at the predefined coordinates reveals the buccal branch immediately deep to the surface marking. Intraoperative nerve stimulation is used to confirm branch identity. When clinically indicated, retrograde dissection is subsequently performed to facilitate identification of the main facial nerve trunk and additional branches.

Observations: Across a series of illustrative cases, including selective neurectomy, masseteric to facial nerve transfer, parotid tumor dissection, and rhytidectomy, the method enabled consistent and efficient identification of the buccal branch. The approach allowed nerve isolation through a limited preauricular incision, reducing the need for direct cheek incisions or extensive deep plane exposure.

Conclusion: Tommy’s 3-5-7 method offers a practical and minimally invasive technique for localization of the buccal branch of the facial nerve. This video demonstrates its value as a precise and efficient tool for surgeons performing branch level facial nerve dissection.

Video. Tommy’s 3-5-7 method. A surface-landmark technique for minimally invasive facial nerve identification. This video presents a step-by-step demonstration of the 3-5-7 coordinate system for localization of the buccal branch of the facial nerve. The surface landmarks are defined as 3.5 cm anterior and 0.7 cm caudal to the tragus. The surgical sequence illustrates subcutaneous elevation, entry of the superficial musculoaponeurotic system (SMAS) at the predefined coordinates, and direct identification of the buccal branch. Following confirmation, the dissection is extended to adjacent branches, including the zygomatic, temporal, marginal mandibular, and cervical branches, demonstrating the applicability of this technique in procedures such as selective neurectomy.

Precise identification of the facial nerve and its branches remains a cornerstone of head and neck surgery, encompassing procedures such as facial reanimation, parotidectomy, trauma reconstruction, and aesthetic rhytidectomy. Standardized localization methods are essential to optimize operative efficiency, reduce the risk of iatrogenic injury, and preserve facial function. As such, reliable intraoperative identification directly influences both surgical safety and functional outcomes.

Nevertheless, consistent localization remains challenging, reflecting inherent anatomical complexity. Despite advances in anatomical mapping and refinements in surgical technique, the facial nerve’s intricate course and substantial variability in branching patterns continue to pose significant obstacles during intraoperative identification. These factors collectively highlight the persistent gap between anatomical knowledge and practical, reproducible nerve localization in the operative setting.

Limitations of Proximal Facial Nerve Landmarks

To address anatomical variability of the facial nerve, surgeons have traditionally relied on deep-tissue landmarks to identify the main facial nerve trunk. Established proximal localization techniques, including Borle’s triangle [1], May’s triangle [2], and Conley’s (Trident) triangle [3], have demonstrated high accuracy in both cadaveric studies and clinical practice. These techniques are widely adopted as reliable reference points for trunk-level identification of the facial nerve.

Despite their proven reliability, these approaches require extensive deep dissection to expose proximal nerve segments. This requirement introduces substantial technical challenges, particularly in scarred, previously operated, or revision surgical fields, where normal tissue planes are distorted and less clearly defined. In such settings, deep dissection can increase operative complexity and prolong surgical time.

Moreover, initiating dissection at the main trunk is procedurally inefficient when the primary surgical objective is selective access to distal facial nerve branches. This discrepancy between surgical intent and dissection strategy highlights the need for alternative localization methods that enable more targeted and efficient branch-level identification.

Challenges of Distal Facial Nerve Identification

To limit the invasiveness of deep proximal exposure, distal branch identification using surface landmarks is commonly applied in clinical practice, particularly in procedures such as nerve protection during parotidectomy, selective neurectomy, and facial nerve reconstruction.

Zuker’s point [4], a surface landmark located midway between the root of the helix and the oral commissure, is widely used to identify the middle division of the facial nerve responsible for smile function. While this landmark provides consistent identification of the target branch, its distal location necessitates retrograde dissection when additional zygomatic or buccal branches require exploration, thereby increasing operative complexity.

Direct cheek incisions may further facilitate nerve exposure but carry a risk of visible scarring that may be unacceptable in certain patient populations. Collectively, these limitations support the need for a more proximal localization approach that enables accurate facial nerve identification through a concealed preauricular incision.

To address the tradeoff between the invasiveness of deep proximal dissection and the aesthetic concerns associated with distal facial incisions, we developed a novel localization strategy that prioritizes both surgical precision and cosmetic preservation. Designated Tommy’s 3-5-7 method, this technique provides a simplified, surface-based approach for selective identification of the buccal branch while minimizing the extent of tissue exposure. By integrating predictable surface landmarks with targeted dissection, the method aims to improve procedural efficiency without compromising anatomical accuracy.

The technique has been applied across a range of clinical scenarios that require precise branch-level localization, including selective neurectomy, facial reanimation, facial trauma repair, facial nerve schwannoma surgery, and parotid tumor resection. In this video article, we present a step-by-step demonstration of the method to illustrate its practical application, reproducibility, and effectiveness in isolating the buccal branch of the facial nerve.

Clinical Indications and Surgical Utility

To translate anatomical precision into clinical practice, this section delineates the surgical scenarios in which Tommy’s 3-5-7 method offers advantages over traditional approaches. The technique is indicated when safe, rapid, and selective identification of the buccal branch is required, with minimal dissection and maximal preservation of surrounding soft tissue. These indications define settings in which precise branch localization is central to operative success.

Functional reconstruction

Primary indications focus on functional reconstruction. These include selective neurectomy for post-paralytic facial synkinesis, and facial reanimation procedures, such as masseteric-to-facial nerve transfer, selective coaptation for functioning free muscle transplantation, and cross-face nerve grafting.

Parotid and aesthetic surgery

The technique also proves valuable in routine and aesthetic preservation. It is indicated during primary or revision parotid and peri-parotid surgery to preserve the buccal branch while limiting the extent of the dissection field. Additionally, it provides significant utility in aesthetic surgery, specifically during superficial musculoaponeurotic system (SMAS) or deep-plane facelifts, where precise branch localization mitigates the risk of iatrogenic injury.

Complex secondary interventions

Finally, the method demonstrates particular strength in complex secondary procedures performed in scarred or radiated operative fields. In these settings, normal anatomical planes are distorted, and conventional landmarks become unreliable. Clearly defined surface-based landmarks therefore simplify initial branch mapping and provide a dependable starting point before the surgeon proceeds with careful retrograde dissection toward the main facial nerve trunk.

Operational advantages

Across these clinical contexts, the method facilitates intraoperative nerve confirmation through stimulation, allowing early verification of branch identity. This precision supports targeted neurorrhaphy or controlled dissection, while limiting unnecessary tissue manipulation, reducing operative trauma, and minimizing postoperative scarring.

Operative Technique

Preoperative preparation and surface markings

The patient is placed under general anesthesia in the supine position, with the head turned slightly toward the contralateral side to optimize exposure of the operative field. To preserve the accuracy of intraoperative nerve monitoring, neuromuscular blockade is avoided. Local hemostasis is achieved by infiltrating epinephrine at a concentration of 1:200,000 five minutes before skin incision. This anesthetic strategy ensures both adequate operative conditions and reliable electrophysiologic confirmation of facial nerve function.

Surface marking is performed using the tragus as the primary anatomical reference point. A vertical imaginary line is drawn immediately anterior to the tragus. Along this line, the first reference point is marked 3.5 cm anterior to the tragus. From this point, a second mark is placed 0.7 cm caudal (Figure 1A, Video). These coordinates, 3.5 cm anterior and 0.7 cm caudal, form the anatomical basis of the “3-5-7” nomenclature. This defined surface coordinate represents the anticipated emergence of the facial nerve buccal branch beneath the SMAS.

By relying on a consistent tragal reference rather than variable soft tissue landmarks, this method provides a precise and reproducible guide for branch level localization. This approach reduces anatomic uncertainty and facilitates targeted dissection while minimizing unnecessary tissue manipulation.

Figure 1. Surgical sequence and anatomical landmarks of Tommy’s 3-5-7 method for facial nerve identification. (A) Preoperative surface markings. A vertical reference line is drawn immediately anterior to the tragus. The target point for the buccal branch is defined by marking a location 3.5 cm anterior to the tragus, followed by a second mark placed 0.7 cm caudal to this point. (B) Intraoperative verification. After a 5-cm preauricular incision and elevation of the subcutaneous skin flap, the predefined coordinates are reidentified on the exposed superficial musculoaponeurotic system (SMAS). This step confirms the intended site for SMAS entry before deep dissection. (C) Targeted dissection. Blunt dissection through the SMAS and parotid fascia at the designated location reveals the buccal branch immediately deep to the surface marking. (D) Retrograde dissection and branch exposure. After identification of the buccal branch, retrograde dissection is performed to expose the main facial nerve trunk and to facilitate subsequent identification of additional branches, including the zygomatic, temporal, marginal mandibular, and cervical branches. (E) Anatomical comparison of landmarks. A schematic comparison illustrates the proximal location of Tommy’s point, defined by the 3-5-7 coordinates, relative to the more distal Zuker’s point. Localization using Tommy’s point permits nerve identification through a preauricular incision, thereby offering a cosmetic advantage by avoiding a direct cheek incision.

Incision and exposure of the SMAS

Guided by the predefined surface markings, the surgeon initiates surgical access through a preauricular approach. A 5-cm preauricular incision is made, beginning within the temporal scalp, coursing immediately anterior to the tragus, and extending inferiorly beneath the earlobe. Subcutaneous dissection is then performed to elevate a skin flap in the preauricular region, allowing exposure of the SMAS and the underlying parotid fascia. This stepwise exposure preserves tissue planes while maintaining orientation to the premarked surface coordinates. Before entering the SMAS, the surgeon reconfirms the buccal branch landmark to ensure accurate alignment with the planned site of SMAS dissection (Figure 1B).

Targeted dissection and nerve verification

Dissection begins with gentle spreading of the SMAS and parotid fascia at the predefined coordinates to isolate the buccal branch, which typically lies directly beneath the surface mark (Figure 1C). This targeted approach leverages the predictable sub-SMAS anatomy to limit dissection while maintaining precise spatial orientation. The defined sub-SMAS target facilitates efficient nerve confirmation using electrical stimulation, allowing either targeted neurorrhaphy or safe branch dissection, depending on the operative objective. A nerve stimulator is used to identify motor branches that elicit perioral or nasolabial movement, thereby confirming buccal branch activation. Bipolar coagulation is applied as needed to achieve hemostasis.

Retrograde dissection and branch extension

After identification of the buccal branch, dissection proceeds based on the specific surgical indication. This process typically involves retrograde dissection from the buccal branch toward the main facial nerve trunk, followed by identification of additional branches, including the zygomatic, frontal, and marginal mandibular branches (Figure 1D). This retrograde strategy provides controlled expansion of the operative field while preserving anatomic continuity between branches. Retrograde dissection preserves fascicular architecture and facilitates nerve coaptation, which is a critical consideration in reconstructive procedures such as facial nerve transfers. Throughout this stage, the surgeon advances cautiously along the predefined trajectory established by Tommy’s 3-5-7 method. In experienced hands, adjacent branches may be identified within the same dissection plane without requiring extensive tissue exposure.

Presented as a Video Article, this manuscript introduces a novel anatomical concept and a standardized surgical workflow. The primary objective is to demonstrate technical feasibility and procedural reproducibility rather than to provide a statistical analysis derived from a large cohort. Accordingly, the findings are framed as descriptive intraoperative observations that reflect procedural consistency and an acceptable safety profile within a defined clinical context. Future prospective and comparative studies are planned to further quantify outcomes and validate these observations across broader populations.

In our institutional experience, Tommy’s 3-5-7 method has been applied across a spectrum of procedures, including facial reanimation, such as masseteric to facial nerve transfer, selective neurectomy, parotidectomy, and aesthetic rhytidectomy. When the described surface landmarks are followed precisely, the technique may allow consistent identification of the buccal branch, thereby reducing the need for extensive dissection or direct cheek incisions. This predictable localization may facilitate efficient retrograde mapping of the main facial nerve trunk and adjacent branches when clinically indicated.

Importantly, within the scope of these applications, no instances of permanent iatrogenic nerve injury or severe procedure related complications were observed. The use of a limited preauricular approach may also contribute to favorable cosmetic outcomes by avoiding additional visible incisions. On this basis, these observations support the role of Tommy’s 3-5-7 method as a safe and reproducible adjunct for branch level facial nerve identification, while acknowledging the need for further validation through systematic study designs.

Limitations of Distal Surface Landmarks

Accurate identification of the facial nerve and its branches is a critical component of facial reanimation and aesthetic procedures, particularly for minimizing iatrogenic injury and optimizing functional outcomes. Multiple anatomical landmark based techniques have been proposed to facilitate facial nerve localization, yet each approach carries inherent limitations related to depth, exposure, or surgical accessibility.

Zuker’s point [4] identifies the middle division of the facial nerve at the midpoint between the root of the helix and the oral commissure. Although this landmark demonstrates consistency in cadaveric studies, its clinical utility for comprehensive facial nerve mapping may be limited when compared with more proximal approaches such as Tommy’s 3-5-7 method. The relatively distal position of Zuker’s point corresponds to a smaller nerve fascicle, which may be more challenging to identify at the outset and may require extended retrograde dissection to delineate additional branches.

From a procedural standpoint, the distal location of this landmark imposes constraints on incision planning and dissection strategy. Accessing Zuker’s point through a concealed preauricular incision typically necessitates broad dissection beneath the SMAS, thereby increasing the extent of tissue manipulation. This expanded dissection field may elevate the risk of soft tissue trauma and operative morbidity across a wider facial region, particularly when multiple branches must be identified.

Challenges of Deep Proximal Dissection

Conversely, targeting the proximal facial nerve trunk may circumvent the challenges associated with identifying small caliber distal branches. However, this strategy requires deep surgical exposure, which introduces greater anatomic complexity and procedural risk. Traditional approaches, such as Borle’s triangle [1] and May’s triangle [2], localize the facial nerve trunk using deep anatomic landmarks, including the mastoid tip, the posterior belly of the digastric muscle, the temporomandibular joint, and the mandibular angle.

Although these methods have demonstrated reproducibility and effectiveness in both cadaveric and clinical settings, they necessitate extensive dissection through deep tissue planes. Such exposure may be impractical in clinical scenarios involving large parotid neoplasms or operative fields distorted by prior surgery, fibrosis, or inflammation, where safe and efficient access to the nerve trunk becomes technically demanding. When less invasive access is sufficient, the depth and extent of dissection required by proximal trunk based techniques may increase operative complexity and procedural burden, thereby limiting their applicability in procedures where selective branch identification can achieve the desired surgical objective.

Emerging Techniques and Clinical Gaps

To mitigate the morbidity and technical demands associated with deep dissection, recent investigative efforts have explored hybrid strategies that combine bony landmarks with surface projections, with the goal of balancing anatomic precision and minimally invasive access. Approaches such as Conley’s Trident triangle [3] and the intercept landmark described by Medhurst et al. [5] seek to refine facial nerve localization through intersecting surface reference lines.

Although these techniques have demonstrated promising accuracy in cadaveric studies and may offer utility in procedures involving deep plane dissection, such as rhytidectomy, their effectiveness in live surgical settings has not yet been systematically validated. The absence of prospective clinical data limits conclusions regarding their reproducibility, safety profile, and applicability across varied operative contexts.

In addition, reliance on established distal landmarks, including Zuker’s point [4], may necessitate direct cheek incisions to achieve adequate exposure. Such incisions can compromise aesthetic outcomes and may be less acceptable in patient populations for whom scar concealment is a priority. Consequently, a persistent clinical gap remains for a proximal facial nerve identification strategy that enables accurate localization through a concealed preauricular incision while minimizing dissection and soft tissue disruption.

Anatomical Rationale and Surgical Application

Tommy’s 3-5-7 method addresses the limitations of existing localization strategies by introducing a simplified and anatomically grounded approach for identifying the buccal branch of the facial nerve. The technique uses a vertical reference line anterior to the tragus to localize the nerve at fixed coordinates of 3.5 cm anterior and 0.7 cm caudal to the tragus. These coordinates were derived from repeated intraoperative measurements that consistently localized the buccal branch within a narrow corridor deep to the SMAS. This anatomic consistency supports the use of a predefined surface target rather than reliance on variable soft tissue landmarks.

The designated point corresponds to a predictable targeting window where the nerve lies immediately deep to the SMAS, thereby facilitating rapid and targeted dissection. When anatomic variation is encountered, this point provides a reliable initial zone from which controlled retrograde dissection can be undertaken without expanding the exposure unnecessarily.

This approach offers several procedural advantages. First, reliance on a reproducible surface landmark limits the dissection field required to identify the appropriate donor branch, which may reduce the risk of injury to adjacent facial nerve branches and minimize overall tissue trauma. Second, accurate preoperative localization may decrease the time required for intraoperative nerve identification. This efficiency is particularly relevant in pediatric patients and in technically demanding procedures, including facial reanimation, selective neurectomy, and cross face nerve grafting, where precision is critical. Third, these landmarks delineate a clearly defined critical zone that can guide surgeons during facial procedures such as rhytidectomy and assist in avoiding inadvertent nerve injury. Fourth, the more proximal target reduces the dissection corridor compared with distal landmarks such as Zuker’s point. In our institutional experience, this approach allowed buccal branch identification through a limited 5-cm preauricular incision, thereby avoiding a cheek incision and supporting favorable aesthetic outcomes (Figure 1E).

Based on these observations, the method streamlines the operative workflow by transforming a variable anatomic search into a predictable procedural sequence. This reproducibility facilitates precise nerve confirmation and targeted repair while supporting both functional preservation and aesthetic considerations.

Study Limitations and Future Directions

Although this technique offers potential advantages in operative efficiency and aesthetic outcomes, a rigorous scientific assessment requires careful consideration of its limitations. At present, the proposed method is constrained by its primary focus on the buccal branch and by the absence of large scale clinical validation. Accordingly, the findings should be interpreted as descriptive and hypothesis generating rather than definitive evidence of comparative superiority.

In addition, the potential influence of anatomic variation or altered surface landmarks in patients with a history of prior surgery, trauma, or fibrosis warrants further investigation. The accuracy and reproducibility of this approach across diverse pediatric age groups have also not been fully established. Although extensive clinical experience with Zuker’s point suggests that age related positional changes of the buccal branch may be limited, direct validation of the 3-5-7 coordinates in pediatric populations remains necessary.

Future prospective studies comparing this method with established anatomic localization techniques across a range of ages, patient populations, and surgical indications are necessary to define its reproducibility, generalizability, and long term clinical value.

Tommy’s 3-5-7 method minimizes tissue disruption while providing a reproducible protocol for localization of the buccal branch of the facial nerve. The technique may reduce operative time and support accurate nerve identification, thereby promoting favorable functional outcomes in facial procedures and nerve repair. Overall, it offers a systematic and anatomically grounded framework for safe and precise buccal branch exploration.

We thank Dr. Ronald Zuker for his mentorship and for providing insightful critique of this manuscript. His pioneering contributions to the field have significantly influenced our clinical practice.

Received date: December 07, 2025

Accepted date: December 13, 2025

Published date: December 24, 2025

The manuscript has not been presented or discussed at any scientific meetings, conferences, or seminars related to the topic of the research.

The study adheres to the ethical principles outlined in the 1964 Helsinki Declaration and its subsequent revisions, or other equivalent ethical standards that may be applicable. These ethical standards govern the use of human subjects in research and ensure that the study is conducted in an ethical and responsible manner. The researchers have taken extensive care to ensure that the study complies with all ethical standards and guidelines to protect the well-being and privacy of the participants.

The author(s) of this research wish to declare that the study was conducted without the support of any specific grant from any funding agency in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors. The author(s) conducted the study solely with their own resources, without any external financial assistance. The lack of financial support from external sources does not in any way impact the integrity or quality of the research presented in this article. The author(s) have ensured that the study was conducted according to the highest ethical and scientific standards.

Dr. Tommy Nai-Jen Chang is the founder of the International Microsurgery Club. Aside from this affiliation, the authors declare no financial or competing interests that could influence the integrity of this work. Furthermore, the authors affirm that this manuscript is their original intellectual property and that no undeclared third parties have contributed significantly to its content.

It is imperative to acknowledge that the opinions and statements articulated in this article are the exclusive responsibility of the author(s), and do not necessarily reflect the views or opinions of their affiliated institutions, the publishing house, editors, or other reviewers. Furthermore, the publisher does not endorse or guarantee the accuracy of any statements made by the manufacturer(s) or author(s). These disclaimers emphasize the importance of respecting the author(s)' autonomy and the ability to express their own opinions regarding the subject matter, as well as those readers should exercise their own discretion in understanding the information provided. The position of the author(s) as well as their level of expertise in the subject area must be discerned, while also exercising critical thinking skills to arrive at an independent conclusion. As such, it is essential to approach the information in this article with an open mind and a discerning outlook.

© 2025 The Author(s). The article presented here is openly accessible under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (CC-BY). This license grants the right for the material to be used, distributed, and reproduced in any way by anyone, provided that the original author(s), copyright holder(s), and the journal of publication are properly credited and cited as the source of the material. We follow accepted academic practices to ensure that proper credit is given to the original author(s) and the copyright holder(s), and that the original publication in this journal is cited accurately. Any use, distribution, or reproduction of the material must be consistent with the terms and conditions of the CC-BY license, and must not be compiled, distributed, or reproduced in a manner that is inconsistent with these terms and conditions. We encourage the use and dissemination of this material in a manner that respects and acknowledges the intellectual property rights of the original author(s) and copyright holder(s), and the importance of proper citation and attribution in academic publishing.

Video Tommy’s 3-5-7 method. A surface-landmark technique for minimally invasive facial nerve identification. This video provides a step-by-step guide to using the 3-5-7 coordinate system to localize the buccal branch. The landmarks are defined as 3.5 cm anterior and 0.7 cm caudal to the tragus. The surgical sequence demonstrates subcutaneous elevation, SMAS entry at these precise coordinates, and the direct isolation of the buccal branch. Following identification, the footage shows the extension of dissection to adjacent branches, illustrating the technique

This case report describes authors successfully attempt to perform a topographically correct sural nerve transplantation in the extracranial facial nerve stem using the intraneural facial nerve stem topography proposed by Meissl in 1979. This is the first reported case of successful fascicular nerve grafting of the facial nerve stem following extensive laceration.

This article presents a groundbreaking surgical approach for treating facial paralysis, focusing on the combination of the pronator quadratus muscle (PQM) and the radial forearm flap (RFF). It addresses the challenges in restoring facial functions and skin closure in paralysis cases. The study's novelty lies in its detailed examination of the PQM's vascular anatomy when combined with the RFF, a topic previously unexplored. Through meticulous dissections, it provides crucial anatomical insights essential for enhancing facial reanimation surgeries, offering significant benefits in medical practices related to facial reconstruction and nerve transfer techniques.

The communication among international microsurgeons have switched from one direction (from paper, textbook) to multiway interactions through the internet. The authors believe the online platform will play an immensely important role in the learning and development in the field of microsurgery.

Traditionally, suturing techniques have been the mainstay for microvascular anastomoses, but owing to its technical difficulty and labour intensity, considerable work has gone into the development of sutureless microvascular anastomoses. In this review, the authors take a brief look at the developments of this technology through the years, with a focus on the more recent developments of laser-assisted vascular anastomoses, the unilink system, vascular closure staples, tissue adhesives, and magnets. Their working principles, with what has been found concerning their advantages and disadvantages are discussed.

Prof. Koushima, president of World Society for Reconstructive Microsurgery, proposes an innovative concept and technique of the multi-stage ‘Orochi’ combined flaps (sequential flaps in parallel). The technique opens a new vista in reconstructive microsurgery.

The video presents a useful technique for microvascular anastomosis in reconstructive surgery of the head and neck. It is advantageous to use this series of sutures when working with limited space, weak vessels (vessels irradiated, or with atheroclastic plaques), suturing in tension, or suturing smaller vessels (less than 0.8 cm in diameter).

Authors discuss a silicone tube that provides structural support to vessels throughout the entire precarious suturing process. This modification of the conventional microvascular anastomosis technique may facilitate initial skill acquisition using the rat model.

PEDs can be used as alternative means of magnification in microsurgery training considering that they are superior to surgical loupes in magnification, FOV and WD ranges, allowing greater operational versatility in microsurgical maneuvers, its behavior being closer to that of surgical microscopes in some optical characteristics. These devices have a lower cost than microscopes and some brands of surgical loupes, greater accessibility in the market and innovation plasticity through technological and physical applications and accessories with respect to classical magnification devices. Although PEDs own advanced technological features such as high-quality cameras and electronic loupes applications to improve the visualizations, it is important to continue the development of better technological applications and accessories for microsurgical practice, and additionally, it is important to produce evidence of its application at surgery room.

Avulsion injuries and replantation of the upper arm are particularly challenging in the field of traumatic microsurgery. At present, the functional recovery of the avulsion injuries upper arm after the replantation is generally not ideal enough, and there is no guideline for the surgeries. The aim of this study was to analyze the causes of failure of the upper arm replantation for avulsion injuries, summarize the upper arm replantation’s indications, and improve the replantation methods.

The supraclavicular flap has gained popularity in recent years as a reliable and easily harvested flap with occasional anatomical variations in the course of the pedicle. The study shows how the determination of the dominant pedicle may be aided with indocyanine green angiography. Additionally, the authors demonstrate how they convert a supraclavicular flap to a free flap if the dominant pedicle is unfavorable to a pedicled flap design.

The implications of rebound heparin hypercoagulability following cessation of therapy in microsurgery is unreported. In this article the authors report two cases of late digit circulatory compromise shortly after withdrawal of heparin therapy. The authors also propose potential consideration for changes in perioperative anticoagulation practice to reduce this risk.

In a cost-effective and portable way, a novel method was developed to assist trainees in spinal surgery to gain and develop microsurgery skills, which will increase self-confidence. Residents at a spine surgery center were assessed before and after training on the effectiveness of a simulation training model. The participants who used the training model completed the exercise in less than 22 minutes, but none could do it in less than 30 minutes previously. The research team created a comprehensive model to train junior surgeons advanced spine microsurgery skills. The article contains valuable information for readers.

The loupe plays a critical role in the microsurgeon's arsenal, helping to provide intricate details. In the absence of adequate subcutaneous fat, the prismatic lens of the spectacle model may exert enormous pressure on the delicate skin of the nasal bone. By developing a soft nasal support, the author has incorporated the principle of offloading into an elegant, simple yet brilliant innovation. A simple procedure such as this could prove invaluable for microsurgeons who suffer from nasal discoloration or pain as a result of prolonged use of prismatic loupes. With this technique, 42% of the pressure applied to the nose is reduced.

An examination of plastic surgery residents' experiences with microsurgery in Latin American countries was conducted in a cross-sectional study with 129 microsurgeons. The project also identifies ways to increase the number of trained microsurgeons in the region. The authors claim that there are few resident plastic surgeons in Latin America who are capable of attaining the level of experience necessary to function as independent microsurgeons. It is believed that international microsurgical fellowships would be an effective strategy for improving the situation.

This retrospective study on the keystone design perforator island flap (KDPIF) reconstruction offers valuable insights and compelling reasons for readers to engage with the article. By sharing clinical experience and reporting outcomes, the study provides evidence of the efficacy and safety profile of KDPIF as a reconstructive technique for soft tissue defects. The findings highlight the versatility, simplicity, and favorable outcomes associated with KDPIF, making it an essential read for plastic surgeons and researchers in the field. Surgeons worldwide have shown substantial interest in KDPIF, and this study contributes to the expanding knowledge base, reinforcing its clinical significance. Moreover, the study's comprehensive analysis of various parameters, including flap survival rate, complications, donor site morbidity, and scar assessment, enhances the understanding of the procedure's outcomes and potential benefits. The insights garnered from this research not only validate the widespread adoption of KDPIF but also provide valuable guidance for optimizing soft tissue reconstruction in diverse clinical scenarios. For readers seeking to explore innovative reconstructive techniques and improve patient outcomes, this article offers valuable knowledge and practical insights.

This comprehensive review article presents a profound exploration of critical facets within the realm of microsurgery, challenging existing paradigms. Through meticulous examination, the authors illuminate the intricate world of microangiosomes, dissection planes, and the clinical relevance of anatomical structures. Central to this discourse is an exhaustive comparative analysis of dermal plexus flaps, meticulously dissecting the viability and potential grafting applications of subdermal versus deep-dermal plexi. Augmenting this intellectual voyage are detailed illustrations, guiding readers through the intricate microanatomy underlying skin and adjacent tissues. This synthesis of knowledge not only redefines existing microsurgical principles but also opens new frontiers. By unearthing novel perspectives on microangiosomes and dissection planes and by offering a comparative insight into dermal plexus flaps, this work reshapes the landscape of microsurgery. These elucidations, coupled with visual aids, equip practitioners with invaluable insights for practical integration, promising to propel the field of microsurgery to unprecedented heights.

This article presents a groundbreaking surgical approach for treating facial paralysis, focusing on the combination of the pronator quadratus muscle (PQM) and the radial forearm flap (RFF). It addresses the challenges in restoring facial functions and skin closure in paralysis cases. The study's novelty lies in its detailed examination of the PQM's vascular anatomy when combined with the RFF, a topic previously unexplored. Through meticulous dissections, it provides crucial anatomical insights essential for enhancing facial reanimation surgeries, offering significant benefits in medical practices related to facial reconstruction and nerve transfer techniques.

This article exemplifies a significant advancement in microsurgical techniques, highlighting the integration of robotic-assisted surgery into the deep inferior epigastric perforator (DIEP) flap procedure for breast reconstruction. It demonstrates how innovative robotic technology refines traditional methods, reducing the invasiveness of surgeries and potentially lessening postoperative complications like pain and herniation by minimizing the length of the fascial incision. This manuscript is pivotal for professionals in the medical field, especially those specializing in plastic surgery, as it provides a comprehensive overview of the operative techniques, benefits, and critical insights into successful implementation. Moreover, it underscores the importance of ongoing research and adaptation in surgical practices to enhance patient outcomes. The article serves as a must-read, not only for its immediate clinical implications but also for its role in setting the stage for future innovations in robotic-assisted microsurgery.

The groundbreaking study illuminates the complex mechanisms of nerve regeneration within fasciocutaneous flaps through meticulous neurohistological evaluation, setting a new benchmark in experimental microsurgery. It challenges existing paradigms by demonstrating the transformative potential of sensory neurorrhaphy in animal models, suggesting possible clinical applications. The data reveal a dynamic interplay of nerve recovery and degeneration, offering critical insights that could revolutionize trauma management and reconstructive techniques. By bridging experimental findings with hypothetical clinical scenarios, this article inspires continued innovation and research, aimed at enhancing the efficacy of flap surgeries in restoring function and sensation, thus profoundly impacting future therapeutic strategies.

This article presents the first comprehensive review of refractory chylous ascites associated with systemic lupus erythematosus, analyzing 19 cases to propose an evidence-based therapeutic framework. It introduces lymphatic bypass surgery as an effective option for this rare complication, overcoming the limitations of conventional treatment. By integrating mechanical drainage, immunomodulation, and lymphangiogenesis, this approach achieves rapid and sustained resolution of ascites. The findings offer a novel surgical strategy for autoimmune lymphatic disorders and prompt a re-evaluation of their complex pathophysiology. This study demonstrates how surgical innovation can succeed where traditional therapies fail, offering new hope in managing refractory autoimmune disease.

This case highlights the use of a bipedicled deep inferior epigastric perforator (DIEP) flap for reconstructing a massive 45 × 17 cm chest wall defect following bilateral mastectomy. By preserving abdominal musculature and utilizing preoperative computed tomographic angiography (CTA) for perforator mapping, the technique enabled tension-free bilateral microvascular anastomosis to the internal mammary arteries. The incorporation of submuscular mesh and minimal donor-site undermining maintained abdominal wall integrity. At six-month follow-up, no hernia or functional deficits were observed, and the patient reported high satisfaction on the BREAST-Q. This muscle-sparing strategy offers a viable alternative for large, midline-crossing chest wall defects where conventional flaps may be insufficient.

Motorcycle chain-induced fingertip amputations represent a reconstructive dead end, where severe crushing and contamination traditionally compel revision amputation. The authors dismantle this exclusion criterion, reporting an 83% salvage rate using a modified protocol of radical debridement, strategic skeletal shortening, and simplified single-vessel supermicrosurgery. By eschewing complex grafting for tension-free primary anastomosis, the authors successfully restored perfusion in ostensibly

Authors present a case of combined proximal median and ulnar nerves extensive injury that was successfully managed using a novel safe strategy implemented.

A significant increase in peripheral nerve surgery has occurred in recent years due to improvements in surgical techniques. In most reconstructive procedures, sensory restoration is frequently neglected in preference to restoring motor function. Along with increasing the risk of developing injuries to the body, patients who lose protective sensations are more likely to develop neuropathic pain and depression, which adversely affect their quality of life. As regaining sensory function is important, the study examines a variety of techniques that may be useful for restoring sensory function across various body parts.

A significant increase in peripheral nerve surgery has occurred in recent years due to improvements in surgical techniques. In most reconstructive procedures, sensory restoration is frequently neglected in preference to restoring motor function. Along with increasing the risk of developing injuries to the body, patients who lose protective sensations are more likely to develop neuropathic pain and depression, which adversely affect their quality of life. As regaining sensory function is important, the study examines a variety of techniques that may be useful for restoring sensory function across various body parts.

This study introduces an advanced tubularized radial artery forearm flap (RAFF) technique, marking an enhancement over traditional methods in addressing complex nasal reconstructions. It integrates functional and aesthetic considerations through a structured, multi-stage reconstruction process, emphasizing the use of tubularized flaps. Key learning points include the detailed crafting of stable nasal passages, strategic use of costal cartilage for robust structural support, and tailored postoperative care with silicone splints. The tubularized RAFF technique not only optimizes patient outcomes and quality of life but also provides plastic surgeons with critical insights to refine their techniques in facial reconstruction. Indispensable for professionals in the field, this article enriches the understanding of sophisticated reconstructive challenges and solutions.

This article presents a crucial case report on potential wound healing complications linked to fremanezumab, a calcitonin gene-related peptide-targeting antibody for migraine prevention. It documents the first known instance of delayed wound healing following a free flap breast reconstruction, underscoring the need for heightened clinical vigilance and individualized patient assessment in perioperative settings. Highlighting significant safety data gaps, the report advocates for comprehensive research and rigorous post-marketing surveillance. The findings emphasize the importance of balancing the risks of delayed wound healing with the need for effective disease control, especially when using biologic agents for chronic conditions. This article is essential for medical professionals managing patients on biologic therapies, offering critical insights and advocating for a personalized approach to optimize patient outcomes. By presenting novel observations and calling for further investigation, it serves as a vital resource for enhancing patient care and safety standards in the context of biologic treatments and surgical interventions.

This manuscript showcases an advanced surgical approach for treating malignant giant cell tumor of bone, emphasizing precision and ethical considerations. It leverages innovative pedicled flap technologies, as opposed to free flaps, enhancing limb functionality and patient quality of life. This technique equips surgeons with evidence that tailored surgical strategies can significantly improve outcomes in complex cases. The paper discusses technical challenges and highlights the application of supercharging and superdrainage techniques in limb reconstructions, methods well-established in microsurgery but infrequently used in oncological contexts. These techniques are crucial for optimizing flap viability and ensuring surgical success. Additionally, the manuscript underscores the profound impact of these advancements on patient lives, offering hope and showcasing tangible benefits. This narrative, blending scientific analysis with patient stories, enriches the understanding of limb reconstruction innovations in oncological surgery, making it invaluable for surgeons.

This article presents the first comprehensive review of refractory chylous ascites associated with systemic lupus erythematosus, analyzing 19 cases to propose an evidence-based therapeutic framework. It introduces lymphatic bypass surgery as an effective option for this rare complication, overcoming the limitations of conventional treatment. By integrating mechanical drainage, immunomodulation, and lymphangiogenesis, this approach achieves rapid and sustained resolution of ascites. The findings offer a novel surgical strategy for autoimmune lymphatic disorders and prompt a re-evaluation of their complex pathophysiology. This study demonstrates how surgical innovation can succeed where traditional therapies fail, offering new hope in managing refractory autoimmune disease.

Motorcycle chain-induced fingertip amputations represent a reconstructive dead end, where severe crushing and contamination traditionally compel revision amputation. The authors dismantle this exclusion criterion, reporting an 83% salvage rate using a modified protocol of radical debridement, strategic skeletal shortening, and simplified single-vessel supermicrosurgery. By eschewing complex grafting for tension-free primary anastomosis, the authors successfully restored perfusion in ostensibly

By translating facial nerve anatomy into geometric coordinates (3.5 cm anterior and 0.7 cm caudal to the tragus), this study proposes a standardized and minimally invasive strategy. This approach addresses specific clinical limitations, effectively avoiding the cheek scarring associated with Zuker’s point and reducing the need for extensive dissection to locate the main nerve trunk. Regarding the educational aspect, it was noted by the reviewers that the mnemonic holds potential for lowering the learning curve and facilitating surgical training. We classify this work as a noteworthy "Proof of Concept." While we recognize that large-scale data regarding anatomical variations is pending, the study is valuable because the defined "Critical Zone" offers a necessary safety guide for high-risk deep-plane procedures. Consequently, despite the current reliance on intraoperative nerve monitoring as a safeguard, this work aligns with our emphasis on patient-centered innovation and surgical safety.

The "Tommy's 3-5-7 Method" employs a coordinate system based on the tragus (3.5 cm anterior and 0.7 cm caudal) to shift nerve identification proximally. This approach effectively avoids the extensive distal dissection associated with Zuker's Point and potentially minimizes cheek scarring through a limited 5 cm preauricular incision. This offers a clear benefit for aesthetic outcomes in selective neurectomy and facial reanimation. Crucially, the study attempts to transform traditionally variable landmarks into a standardized geometric framework. Although this method is not a guarantee of proficiency, it should be viewed primarily as a standardized auxiliary tool for preoperative planning. In particular, its mnemonic nature may facilitate surgical training and potentially lower the learning curve. Furthermore, it is imperative to note that this technique currently represents Level IV evidence consisting of expert opinion and case series. Therefore, this coordinate system must be strictly paired with intraoperative nerve monitoring and should serve to complement rather than replace meticulous anatomical dissection. These safety limitations have been clearly contextualized in the article. Consequently, I recommend publication based on the logical consistency of the article and its value as a preliminary technical report. It is my belief that once validated by future large-scale study samples, this technique is poised to have a transformative impact on facial nerve surgery.

This study introduces "Tommy's 3-5-7 Method," a standardized geometric framework proposed to reduce anatomical ambiguity during buccal branch identification. Clinically, this proximal entry point avoids the tedious retrograde dissection inherent to traditional distal approaches and potentially mitigates facial scarring via a preauricular incision. By offering a systematic geometric guide, the method may streamline high-precision procedures and serve as a valuable teaching tool. However, this submission serves as a technical demonstration based on institutional experience rather than a validation study. While the technique appears safe in the provided surgical footage, assertions regarding the minimization of iatrogenic injury require caution pending large-scale comparative data. Given its potential utility as a standardized preoperative planning auxiliary tool, I recommend publication as a technical report.

Liu YT, Hill WKF, Chen LWY, Lu JCY, Huang JJ, Chuang DCC, Chang TNJ. Tommy’s 3-5-7 method: A novel surface-landmark technique for minimally invasive identification of the facial nerve buccal branch. Int Microsurg J 2025;9(1):5. https://doi.org/10.24983/scitemed.imj.2025.00203